China is going to eat our lunch and take our jobs on clean energy—an industry that we largely invented—and they are going to do it with a managed economy we don’t have and don’t want (Romm 2009, cited by Friedman 2009, p. A29).

Mitigating the effects of man-made global warming entails reshaping the sectorial structure, changing consumer culture, accelerating technological innovation, and raising public environmental awareness; and, most importantly, the task requires substantial political support for policy leaders so that they may secure immediate, feasible mitigation resolutions to implement long-term climate strategies. Such political support has been considered as needing to be formulated on the basis of a democratic decision-making process in which widening public participation is assumed non-negotiable if legitimately secure agreements are to be reached among various stakeholders to tackle environmentally sensitive problems (OECD

2002; Bulkeley and Mol

2003; Stevenson and Dryzek

2014). As part of climate mitigation strategies, the development of sustainable energy has occurred under a universal cognition that is profoundly dependent on democratic political support. The strategy that has been implemented thus far in many industrial countries has been established through a mode of governance that explicitly requires the strengthening of local public participation; otherwise, it is deemed impossible to contribute accountably to improving environmental policy outcomes (Van Tatenhove and Leroy

2003; Few et al. 2007; Devine-Wright

2012). This assumption is also embedded in an emerging consensus regarding an environmental policy template—sustainable development—that entails central government giving up power to local-level governments and creating a new partnership with non-governmental actors in the formation of environmental policies (WCED

1987; Baker

2015). This has become a dominant policy template adopted by an increasing number of states (Hajer

1997).

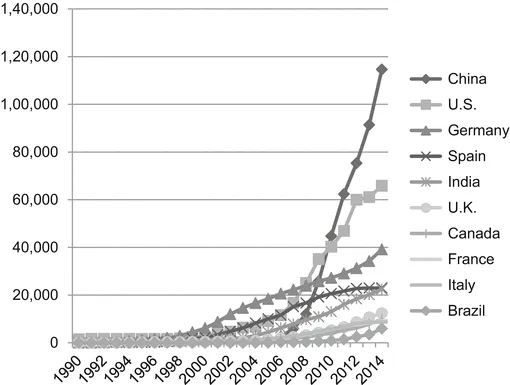

However, it seems that states are committed to the principles; but the practice in relation to this policy template is different. This difference is particularly noticeable in the People’s Republic of China (PRC): China’s renewable energy industry over the past decade has developed with unprecedented speed (Bradsher

2010; Mathews and Tan

2014). The development of the sector has even surpassed that of the sectors of some leading industrial countries and has achieved a number of positive results (REN21

2012; Gallagher

2014). For instance, recent data shows that the country has become the world’s largest wind power market (Lewis

2011b). Figure

1.1 reveals that there has been a sharp growth of installed wind power capacity in China and the country has become the global leader since 2011. In terms of cumulative installed capacity of renewable energy, it is estimated that China has become the largest renewable energy market, globally (Bloomberg News

2013; Dent

2015). Although this phenomenon appears encouraging, the approach that China has adopted does not completely conform to the principles of the default template that it claims to have used (Baker

2015, p. 394). Rather, a decade of change in the sector has been promoted by top-down measures that have unilaterally initiated state-led development strategies to promote the renewable industry in an authoritarian context (Schreurs

2011).

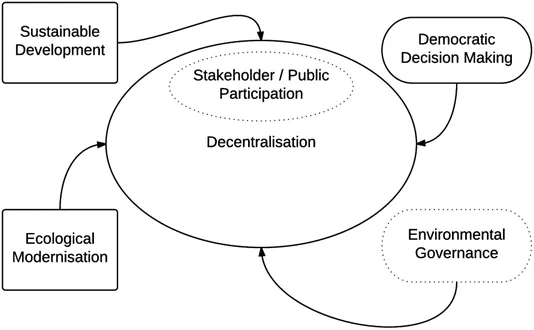

Such strategies and such a governing system potentially contain a fundamental conflict; that is, with respect to the building of environmentalism in contemporary states (whether it is a radical social movement or the recent institutionalisation of sustainable development), the paradigm has been premised on a set of principles that include engagement and dialogues with social and business partners in a broad network of relationships based on underlying democratic, decentralised, and emancipatory ethics (Carter

2007; Paavola

2007; see Fig.

1.2). Whether in the literature or in the practices of environmental governance, decentralised, democratic mechanisms have invariably been considered a necessary condition for the desired policy outcomes. This was written in the

Brundtland Report (WCED

1987) and has been widely cited as a sacrosanct tenet of action in this field. And the emphasis on pluralism and participatory politics has been widely recognised in the governance strategies of most liberal democratic states, seen as the only possible pragmatic approach in industrialised countries for dealing with today’s environmental crisis (Barry and Wissenburg

2001; Stevenson

2013b). In a nutshell, in the orthodoxy of environmental governance, there exists an assumption that derives from the period when environmentalism originated: the assumption that it is necessary to

expand participation to achieve effective environmental policy objectives (Lemos and Agrawal

2006; Sovacool

2013). This default assumption, as shown in Fig.

1.2, is essentially embedded in the model of environmental governance espoused by industrialised states and becomes the template for developing states to follow—a one-size-fits-all model—that is considered an

expedient solution to the environmental crisis.

Aims, Objectives, and Research Questions

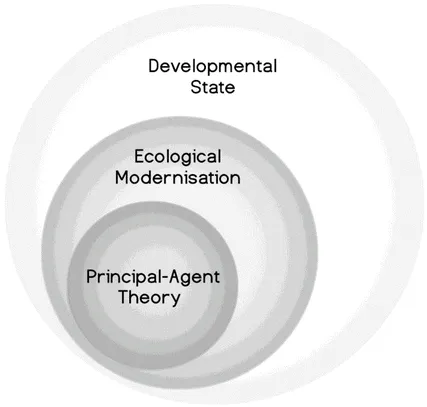

In such a context, how can a non-democratic state manage its transposition of an environmental technology that has been developed under a governance model for the sector that is alien to its own organising principle? The aims of this book are: first to explore the role of the Chinese state in enabling the transformation of the renewable energy sector and to understand the ways in which policy elites seek to introduce a developmental state and ecological modernisation strategy into the policy arena; and second, to analyse agents’ behaviours under such institutional configurations using principal-agent theory. Eventually, using the analytical findings of the research, the possibility is explored of an alternative policy template that may entail a more direct, less participatory, and more target-oriented politics of the environment. Figure

1.3 shows the three theoretical approaches that the book provides from the macro-, meso- and micro-level of investigations. The key research question and the subsequent sub-questions are as follows:

How can a non-democratic state with a gigantic geographic territory manage its transposition of technology-oriented environmental policy and deal with environmental issues that have been premised on decentralisation principles that are alien to its own top-down totalitarian governing principle? 1 In particular, there are five specific questions related to the key inquiry that forms the basis of this book:

1.How does the Chinese state promote renewable energy diffusion through a variety of institutional instruments and mechanisms?

2.How, and to what extent, have the bureaucratic norms and standards of centrally formulated policies influenced the implementation of renewable energy in different regions?

3.What is the governance structure of the renewable energy industry at the local level?

4.How did this form of environmental policy emerge?

5.Can we see a form of environmental politics indicating a new pattern of political behaviour in renewable energy diffusion in which the possibility of less participation and more direct control by the state can deliver an effective outcome to policy objectives?

The Academic Argument of the Book

The book makes the following claims regarding the politics of renewable energy in China. First, as mentioned earlier, it is argued that the Chinese state is engaging in hybrid strategies for environmental protection measures that combine a cluster of ‘developmental state’ features in an attempt to partially incorporate a modified, state-led strategy based on ‘ecological modernisation’. That is, on the basis of the developmental state model, the policy elites have selectively transplanted ecological modernisation practices from the European context; and the central state not only emphasises the imperative of using non-conflictual strategies as a priority but has also selectively institutionalised individual organisations with the co-implantation of a hybrid form of environmental governance, seeking to maximise renewable energy targets. Both approaches have been deployed with the advantage of being conducive to the legitimisation of the existing regime without radically changing the political economic structure, seeking to reconcile the logic of economic development and environmental protection to maintain the stability of the current political regime. This strategy is embedded in the continuing belief and practice that represents exclusively closed state manoeuvrability.

Second, the principal-agent theory is adopted in order to further explore the institutional mechanisms of this model where, in particular, the coercive mechanism maintains a relationship of compliance between central and local governments in China. By looking at the strengthening of the police-patrol-type mechanism, we see how top-down hierarchical authority has maintained compliance with the governance system during the course of renewable energy expansion and, to some extent, facilitated a burgeoning of the emerging industry of climate technologies.

Third, based on the aforementioned arguments, the book claims that centralisation occupies an important place in the governance template used to diffuse renewable energy in China. For many commentators, China appears to be a decentralised authoritarian state 2 that represents a model of the economy in which the central state has delegated its power of policy-making to local government (Lieberthal and Oksenberg 1988; Lin et al. 2006; Cunningham 2010; Toke 2011a; Andrews-Speed 2012; Fewsmith 2012; Landry 2012). This situation has gradually developed since the early 1980s, during which time certain provinces, such as Jiangsu (Breslin 1995, 2007), have shown their financial autonomy. However, according to the findings of local investigations in this book, the empirical evidence shows that the field of renewable energy policy in China seems to contradict existing norms in other policy areas. We have seen a distinct tendency in recent times towards a centralised, top-down attitude to the local governance of the renewable energy industry, and such policy implementation relies on the unusual ability of related coercive mechanisms to control the verticality, while the policy elites have in the meantime attempted to selectively learn policy incentives from the Western model. Whilst continuously learning from the West, the policy elites in China have been reluctant to undermine the capacity of the state by adopting the fashionable dogma of administrative decentralisation, but rather they have paid more attention to strengthening the political control mechanisms of the existing regime. This strategy has replaced the default assumption of decentralisation embedded in the seemingly universally adopted template of environmental governance and seeks to reach technology-oriented policy targets through state intervention by its established non-democratic regime.

The ultimate argument is that such a strategy has unintentionally formed a governance model that differs from the widely adopted orthodox environmental governance model in industrialised countries. In this type of governance structure, the long-term policy objectives are related to managing a perceived environmental crisis and a non-stable situation by giving them priority and, paradoxically, forming a new (although limited to renewable energy) model of governance in an unexpected way. This argument about the dilemma of participatory politics and inherited environmental concerns will be discussed in more detail in the final chapter, indicating how such an unorthodox pattern of governance emerges as a competing model of environmental governance in which renewable energy can be diffused in a less participatory manner, along with more direct controls and target-oriented state intervention that deliver policy objectives that challenge the orthodox assumption that inclusive modes of governance are the only ...