Several Romantic writers have attained the status of ‘icon of locality’. 1 We think most readily, perhaps, of the ‘geographical poet’ Wordsworth in the Lake District, of Scott at Abbotsford or of Burns in south west Scotland. 2 Keats himself made the link between this author and locality explicit in the title of his 1818 northern walking tour poem, ‘Lines Written in the Highlands after a Visit to Burns’s Country’. By contrast, most readers do not associate Keats or his poetry with any particular region, with the exception perhaps of Winchester, to whose geophysical prompts Keats responds in ‘To Autumn’. It is often assumed that the pastoral retreats, woods, bowers and hilly landscapes so characteristic of his work are figurative, literary confections, political displacements or ideological blind spots. In the popular imagination, Keats has become deracinated; his apparent timelessness bespeaks placelessness. For many, he now appears as the dreamy Keats of Benedict Cumberbatch’s ‘chocolately’ RP recital of ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ (a million swooning ‘views’ on YouTube), though it is difficult to imagine a version of Keats more at odds with the young man with a territory-specific Moorfields accent who relied on visits to numerous regional towns and tourist spots, as well as local sights and sounds, to terraform the imaginative regions of his poetry. 3

As a corrective, this book examines Keats’s writing in its geophysical and cultural milieux. At the same time, it investigates the imaginative progressions through which actual locations and visionary poetic terrains enter into—and remain in—complex dialogue. In the past decades, a ‘spatial turn’ in the humanities has applied itself to a more nuanced understanding of the ways in which literary texts are ‘placed in a geography’, and to the processes through which narratives can be ‘“locked” to a particular geography or landscape’. 4 Drawing energy from these parallel strands of inquiry, Keats’s Places—the first full-length geocritical study to examine the coordinates of Keats’s imagination—relocates this strongly platial poet in the topo-poetical grounds of his developing career. 5

1 Place and Practice

Sustained interest in the ‘influence of place … on the writings of Keats’ was first registered in Guy Murchie’s The Spirit of Place in Keats (1955). 6 Murchie’s pioneering study addressed the relation between original topographies and fictional spaces in Keats’s work, focusing on the visual, emotional and philosophical cues provided by various locales and the people encountered there. ‘Boyish impressions’ of medieval chivalric brass work gleaned from the parish church of St Andrew’s Enfield, Murchie suggested, may have been remembered in Keats’s 1816 valentine ‘To [Mary Frogley]’ (‘Hadst thou liv’d when chivalry/ Lifted up her lance on high’, 41). Similarly, architectural features seen in a chapel in Stansted Park appear to have been put to use in The Eve of St Agnes’s ‘sculptur’d dead’ and ‘purgatorial rails’ (14–15). 7 Murchie’s approach adjusted our sense of the importance of actual physical locality to poetic vision, but was not fully calibrated to the complexities that describe the aesthetic, socio-political and psychological correlations between Keats’s experience of Regency geospace and the (un)bounded figurative realms of poetry.

The topic of Keats and place was taken up again a few years later in John Freeman’s Literature and Locality: The Literary Topography of Britain and Ireland (1962). This innovative interdisciplinary project used indexed maps to link geographic areas with writers and their works; in Freeman’s own words, it constituted the ‘first attempt at a comprehensive and systematic guide to the literary topography of the whole of Britain and Ireland’ (Preface). Keats’s birthplace was mapped, together with way stations along his walking tour of the north such as Iona, Mull and Staffa. Freeman’s interest in Keats’s northern peregrinations was taken up in more detail, and with a focus on sense of place, by Carol Kyros Walker’s Walking North with Keats (1992). Footstepping Keats’s 1818 route, Walker examined the poet’s participation in Romantic leisure tourism in terms of the political events of the summer of 1818, notably the Westmorland election. Speaking to a need to see Keats’s places, Walker’s book included evocative photographs of the way marks and terrains described in the tour letters; each image was taken at the appropriate time of year and in matching meteorological conditions. Revealing a fuller range of interaction between physical locality, loco-description and socio-poetic vision, Walker’s volume drew attention to Keats’s growing resistance to the sublime in the epicentre of that ‘high’ aesthetic, at the same time as charting his increasing interest in the poverty he found there.

The 1990s saw theorised interest in Keats as an emplaced poet. The ‘Keats of the suburbs’ emerged at this juncture in persuasive essays by Elizabeth Jones and Alan Bewell. Drawing on the class-centred energies of Marjorie Levinson’s seminal Keats’s Life of Allegory: The Origins of a Style (1988), Jones and Bewell situated Keats and his poetic ‘realm of flora’ in Regency suburbia—a ‘changing urban environment and cultural consciousness that threatened some of the more cherished values of Britain’s established classes’. 8 At this time, a number of critics also began to inspect the ideological contours of a historical socio-political climate in which Keats’s suburbanism could be understood by conservative reviewers explicitly in terms of the liberal values of ‘Cockney’ literary style. Nicholas Roe’s John Keats and the Culture of Dissent (1997) and Jeffery N. Cox’s Poetry and Politics in the Cockney School: Keats, Shelley, Hunt and their Circle (1998) examined the valencies of Keats’s class challenges in terms of a geographically defined group of writers centred on Leigh Hunt’s cottage in Hampstead. ‘Cockney School’ dissent, it became apparent, was not only rooted as an organising practice in the cultural and political resonances of suburbia and the sociality of Hunt’s Vale of Health, but also—much as Keats’s Blackwood’s reviewing bête noire ‘Z.’ (J. G. Lockhart) claimed—in the physical precincts and prospects of peri-urban Hampstead: in its little hills, heathland flora and window boxes.

Romantic scholarship has continued to address and reformulate the question of how, in Fiona Stafford’s words, Keats’s poetry is ‘conditioned by its original location’. 9 Devoting a chapter to ‘Keats’s In-Placeness’, Stafford’s Local Attachments: The Province of Poetry (2010) reads the poet’s efforts to turn from romance to epic through his anxious sense of his work’s precarious place in the ‘immediate world’. For much of his career, Stafford argues, Keats struggled to perceive high art as anything other than ‘fundamentally opposed to “real things”’. 10 Stafford is also alert to Keats’s frustration with the ‘inadequacy of mere description’ to represent physical topographies such as the Cumbrian mountains or natural wonders like Fingal’s Cave. Her emphasis in Local Attachments lies, finally, however, more with the personal placings and displacements of poetry than with the poetry of personal places (such as Hampstead heath, the influence of whose flora on Keats’s writing forms the focus of her chapter in the current volume).

Ongoing work on place and text in Romantic Studies has received energising impetus from the emergence of literary geography, a methodologically sophisticated interdisciplinary approach located at the intersection of human geography, regional studies, cartography, cultural studies and literary analysis. 11 Unsurprisingly, perhaps, Wordsworth’s topographical figures have attracted the lion’s share of attention. A tour-de-force example is Damian Walford Davies’s hydrographic charting of ‘Tintern Abbey’ as a poem materially conditioned by the tidal actions of the Bristol Channel and River Wye. For Walford Davies, the poem ‘exemplifies the merging of the “space” and “practice” of composition/writing’ in the period as much as it represents a ‘chart of Wordsworth’s contact with shifting river- and estuary-scapes’. 12 Such critical shifts reveal the complexities in play as ‘geography conditions the verbal ground’ of Wordsworth’s verse. Romantic Localities (2010), edited by Christoph Bode and Jacqueline Labbe, responds in broad fashion to similar place-centred cues. One of its claims is that the Romantic period witnessed a ‘new development in ideas of place and locale’, a process of reorientation in which ‘place’ was becoming ‘locale’ at the same time as people were becoming ‘locals’ to distinguish themselves from new kinds of ‘visitors’. 13 These complex acts and phenomenologies of emplacement and displacement, the book’s contributors show convincingly, are crucial to the formulation of Romantic writers’ ‘sense of self and subjectivity’ (p. 1). Romantic Localities’ specific commitment to Keats is elaborated by Stefanie Fricke, whose chapter addresses how a group of male Romantic poets constructed politicised geographies by taking up stories of Robin Hood and the ‘greenwood’ as a means of configuring a ‘homosocial space of male bonding’ as an ideal ‘realm of liberty’ (pp. 117–18).

Responding to, extending or revising this energetic tradition of scholarship, the essays in Keats’s Places home in on aspects of the poet’s relation with locations ranging from The Vale of Health, the British Museum and provincial boarding houses to the ‘sites’ of poetic volumes themselves. They reveal that Keats’s places could be comforting, familiar, grounding locales, but also shifting, uncanny, paradoxical spaces where the geographical comes into tension with the familial, the touristic with the medical, the metropolitan with the archipelagic. Taken as a whole, the volume wrestles with the central question of how Keats’s physical landscapes and topographies, towns, villages and cities, tourist spots, retreats and residences inform the mythological and metaphorical ground of his poetry.

2 In and About Town

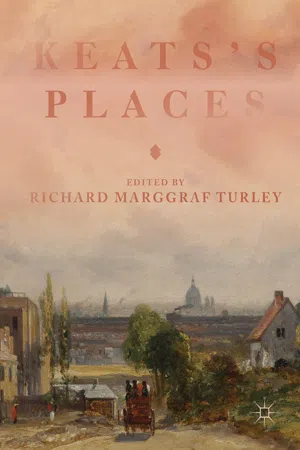

The cover of this book shows John Constable’s plein-air painting, ‘A View of London, with Sir Richard Steele’s House’. Constable’s conceit is that he has set up his easel in the middle of busy Haverstock Hill. 14 The small...