- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

With mega townships as the tool, this book analyses the complexity, scale and the challenges associated with the development paradigm in India from various built environment lenses. The Towers of New Capital is an enquiry into how these 'global fixes' are leading to territorial reorganization.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Towers of New Capital by P. Tiwari in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Challenge of Megacities in India

Piyush Tiwari

Abstract: This chapter sets the stage for discussion in the book by briefly presenting the political, economic and urban context within which mega townships’ development has been envisaged to be at the forefront of India’s aspiration to become a global economy. The chapter also outlines the key literature on the topic. With mega townships as the tool, this book analyses complexity, scale and challenges associated with the development paradigm in India. The chapter also introduces to the readers the interdisciplinary lenses through which mega townships have been analysed in the book.

Tiwari, Piyush, ed. The Towers of New Capital: Mega Townships in India. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. DOI: 10.1057/9781137586261.0005.

Introduction

Globalization has manifested itself in numerous ways – economic, political and social – bestowing its benefits through economic growth and rise in income across nations in global north and south. The past two decades have witnessed phenomenal economic growth in emerging economies like India, China, Brazil, Russia, South Africa and emergence of cities in these economies as crucible of energy and abundant human activity. Now cities in the developing world aspire to become a ‘world city’ or a ‘global city’ as their economies link up with the international markets. In order to attract capital, nations’ governments have started to intervene through space-based interventions in urban regions (Brenner, 1998). Some examples of such interventions (termed ‘global fixes’ by Brenner, 1998) in India are Special Economic Zones or mega townships on the fringes of the existing megacities. As strategies of territorial restructuring, these projects are socially produced and intended to facilitate capital investment and accumulation (Kennedy et al., 2011, quoting Brenner, 1998). There is increasing evidence that policymakers in emerging countries are adopting city-centric strategies, but there is significant variation in the specific model used which depends on each country’s economy; its engagement with global capitalism; and local, social and political institutions (Kennedy et al., 2011); India is no exception and the model, albeit with its many variants, has largely been space-based, infrastructure-led intervention.

Some argue that the role of infrastructure is changing from simply being the precondition for production and consumption to being at the very core of the globalization of economic activities (Flyvbjerg et al., 2003). This results in facilitating infrastructure to be built as megaprojects despite the performance of many such projects being poor in both economic and environmental terms (ibid.). Or, more often than not, when fixing infrastructure on existing cities becomes difficult, these are put together in the form of gated development boasting to provide state-of-the-art infrastructure and amenities as demanded by new capital to locate and attract high-skilled workforce. These gated communities, when the scale is large, take the form of mega townships which are often public-sector led but delivered by the private sector through public–private partnerships. In haste to get these projects started, often these are put together by bypassing the established practices of good governance, transparency and participation in political and administrative decision making (Kennedy et al., 2011).

Tower of New Capital – Mega Townships in India is an enquiry, based on the study of a number of under-development large mega township projects on the urban fringes of Delhi (Noida and Gurgaon) and Ahmedabad, into how are these ‘global fixes’ leading to territorial reorganization? What are the social and economic impacts of large megaprojects? How are these projects envisioned and governed? How transparent is the administrative decision-making process? How are these projects marketed and to whom?

Literature

The starting point for the discussion on the mega townships and their impacts is the literature that attempts to explain the current trend of strategies aimed at creating competitive cities. These studies, see Kennedy (2011) for a review, argue that globalization is forcing states to engage in economic restructuring in order to enable them compete more effectively in global marketplace, and in doing so, states are adopting strategies to create ‘competitive cities’. These global economic processes have predominant impact in shaping local economies. Cities compete with each other within a global market place and in this context local levels are mere filters of global processes (Paul, 2005).

There are many international examples of strategies to create competitive cities/regions internationally. In South Africa, Peet (2002), as quoted in Kennedy et al. (2011), analysed the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) policy in post-apartheid South Africa and found that the policy emphasized on the market system arguing that economic growth and the ‘trickle down’ of its benefits would lead to social upliftment. The GEAR policy was introduced in the Integrated Development Plans of cities, and municipalities were expected to play the enabling role (ibid.). South Africa has sought to invest in megaprojects that it feels would generate appropriate economic returns often by public sector making the investment in these projects first and subsequently seeking to leverage with private capital (Freund, 2010). In this sense, South African approach is a hybrid of market economy and social democratic agendas (Charlton and Kihato, 2006; Harrison, 2006).

On the contrary, the market strategies chosen by Peruvian cities were deregulation of construction and urbanization permits, allowing various forms of privatization in city investments (Kennedy et al., 2011). The process continued with the abolition of the entire planning system in the country resulting in the development of office and retail space without the necessary transport, green space and water and waste water treatment services (ibid.). The dominant strategy of development in Brazil during 1950s and 1960s was to help create ‘corporate metropolis’, which given the constraint on city budgets were concerned with elimination of diseconomies of agglomeration than the production of services for social and collective welfare (Santos, 1990). These policies have led to uneven development patterns in Brazil and the debate now is unanimous in considering that strategic planning (which uses development of specific areas for economic or other objectives as instruments) is incompatible with democracy and practices of participatory planning (Kennedy et al., 2011). These practices have been justified in the name of technical and administrative efficiency (ibid.).

Arguing that urbanization is part of the development processes and cities’ economies benefit from agglomeration, the World Development Report (WDR) (2009) makes the case that cities in developing countries are increasingly serving as engines of economic growth (World Bank, 2009). Though urbanization has caused problems such as congestion, informal settlements and rising demand for urban services in cities, WDR cautions against government seeking to work against urbanization beyond a focus on progressively enhancing access to services and supporting growth-oriented strategies. The policies, however, have been criticized by some as these are accompanied by negative externalities such as marginalization of poor or negative impact on environment (Rigg et al., 2009), and the focus of such policies is on the allocation dimensions while the distribution dimension is not given enough consideration (Kennedy et al., 2011).

Strategies aimed at improving city competitiveness take form within the polity of cities. Another stream of literature situated in political economy discusses the power struggles between different political interest groups within cities and how these interact in managing the city and pursuing growth and development. The questions that are addressed by authors (Kennedy et al., 2011) of such literature are to what extent are countries restructuring their territorial organization by merging municipalities or by creating apex organizations (by bypassing local governments) to adapt to metropolitan regions with regional growth agendas? Do these metropolitan regions become full-fledged political entities or are managed by parastatals, which are outside the local political processes?

The situation becomes far more precarious when local governments are weak. This is particularly the case of India, where though the process of devolution of powers to local government has occurred through 74th Constitutional Amendment Act 1992 (CAA), local governments still remain financially and politically weak and the state governments continue to impose their political powers. Cities do not have sufficient resources or capacity to drive social and economic policy, and the state or the central government continues to drive the process, for instance, with regard to spatial development (Zerah, 2008; HPEC, 2011). Literature argues that external economic constraints and inter-city competition compel officials to focus on attracting investment. While global capital is driving changes at territorial scales, the variation across cities can be explained only by the internal dynamics of local governance (ibid.). Politically mega townships are seen as expressions of public authority even when they are partially financed with public money (Flyvbjerg et al., 2003) and in some cases without the political involvement of local government. India is a case in point where the whole process of SEZ development was driven by the state government pursuing regional growth agenda without the involvement of local political processes. Cities in these circumstances become canvases for political and economic ambitions of upper tiers of governments.

Often the planning processes of mega townships follow less democratic participatory processes which are not integrated in the city planning processes and cause social polarization (Swyngedoum et al., 2002) and are based on exemption from and exemptions to planning laws (Barthel, 2010). Budgets for such projects are often outside the normal city budgets (ibid.). A consequence of the governance of megaprojects is that these take place outside the established modern business areas thereby drawing investments from these areas into new areas often at peripheries, as has happened in Hyderabad, India (Tiwari and Rastogi, 2010).

The impacts of mega townships are the new location of capital mostly in the periphery and the spatial and architectural forms that cause segregation (Levy and Lassult, 2003). These new locations of capital compromise the existing metropolis (Tiwari and Rastogi, 2010), its administrative boundaries and the way they are managed (Kennedy et al., 2011). May et al. (1998), as cited in Kennedy et al. (2011), argue that mega townships are increasingly leading to specialization of urban spaces, which is causing urban fragmentation particularly of material networks such as separate network for water, electricity provision, privatized transport networks and toll roads (Jaglin, 2001, as cited in Kennedy et al., 2011) and create enclaves characterized by restrictions to access and gating (examples are Special Economic Zone development in India). Even though the objective of municipalities through these projects is to generate outcomes that are pro-poor, the results point to the contrary (Robbins, 2005).

Besides the vision and processes that lead to the development of mega townships, literature has also analysed their impact particularly on land values. Tiwari and Rastogi (2010) found substantial gains in land prices in Hyderabad around locations where Special Economic Zones were announced despite that these locations were on the peripheries of the existing city boundaries.

To summarize, mega townships are outcomes of global cities’ vision that cities and nations pursue in the wake of globalization. Theoretical basis such as agglomeration economies is used to justify such large interventions usually at the cost of public exchequer and by bypassing participatory planning processes and in some cases local governments. There is capitalist pressure to execute such projects as it increases private wealth. The distributional inequality that arises is often ignored and the informal arrangements that exist in the cities are bypassed. Even the evidence on the impact on land values of these megaprojects is mixed. In this context, it becomes pertinent to present critical commentary on India’s new towers of capital – mega townships from multidisciplinary perspectives on how these projects are conceptualized, designed and developed; how these projects interface with an existing social and economic landscape; how the interface between old and new identities is transforming cities in India; do old and new coexist to create a unique identity or old starts to pave way, albeit grudgingly, causing despair, loss of cultural identity of built environment. New mega townships are analysed through the built environment disciplinary lenses of property, construction management, architecture, building technology, urban design and planning.

Authors, in this book, have explored land acquisition processes/challenges, urban design outcomes, planning processes, market assessment, construction project management, marketing of such projects to users and investors in an emerging economy context.

The context

The political economy

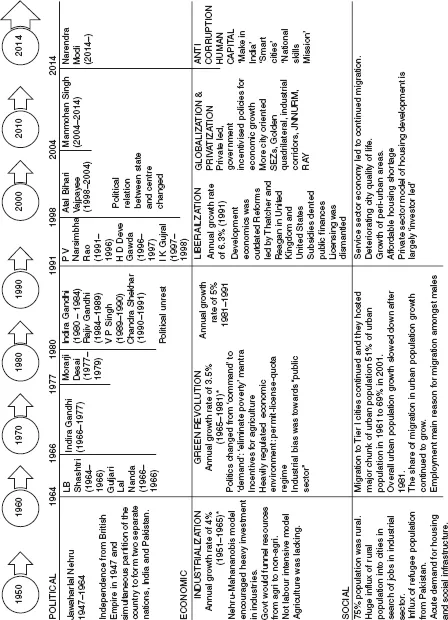

The political, economic and social environment forms the context for new mega townships development. Figure 1.1 presents the snapshot of political, economic and social environment and inter-linkages between them on a temporal scale since India’s independence in 1947.

FIGURE 1.1 Timeline of economic, political and social environment of India since independence (1947)

Source: Author.

During early phases of development under the leadership of Nehru from 1947 to 1964, Indian economic policies focused on self-reliance, imported substitution and development of capital goods industries, and most resources were channelized to the ‘productive’ sectors of the economy viewed myopically as heavy engineering industries. The focus was on cities, which were generating unprecedented employment causing enormous levels of migration from rural to urban. This was complemented with migration flows caused by the partition of count...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 The Challenge of Megacities in India

- 2 Megacity Mismatches: Inequities and Misalignments between the Visions and Realities of Megacity Townships in NCR and Gujarat, India

- 3 New Greenfield Mega Townships of India: Perpetuating the Socio-economic Divide?

- 4 Formality versus Reality: An Exploration of the Development Process for Mega Townships in India

- 5 Perception on Design Quality within the New Mega Townships of India

- 6 The Mouse That Broke the Elephants Back

- 7 Case Studies in Risk Management of Mega Township Development in India

- 8 Governance in Indian Mega Township Development

- 9 Mega Townships: A Marketing Perspective

- 10 Risk and Opportunities in the Indian Real Estate Market

- 11 Ethical Practice in an Emerging Economy

- 12 Global Imaginations: Projection versus Reality in Indian Megaprojects

- 13 Questioning the Approach of Indian Cities towards Development

- Index