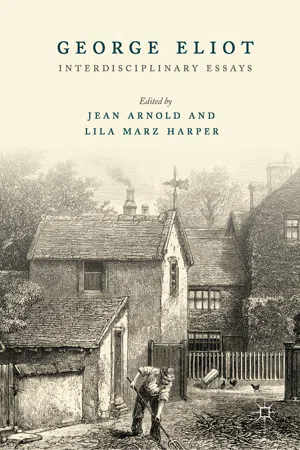

Cover Illustration 1

“Agriculture, after all, is … a craft like poetry”Virgil, Georgica II

In his Georgics, the Roman poet Virgil (70–19 BCE) notes a similarity between different kinds of work; as he puts it,

All labor is the same; the sweat pours downAnd runs distinctions into a salt blur. 2

In the scene pictured on the cover of this collection, and with Virgil’s analogy in mind, the lone human figure could thus represent both farmer and writer. He/she appears to be working hard, judging from the rolled-up shirt sleeves despite the cool weather, as young leaves of early spring appear on the trees, and smoke ascends the chimney. Something tasty must be bubbling in the fireplace pot inside, for a meal is the reward of a farmer’s labor, just as a book signals the end of the writer’s labor: food (f)or thought, these products. If a meal offers sustenance, then so do the readings in this book, which show a labor born of deep respect for George Eliot’s works.

Having spent her formative years in this pictorial setting which depicts “the farm offices” of her childhood home Griff House, George Eliot might have said to herself as Virgil said in his Georgics, yes:

I hope for an easy passage in this bold venture—the scrawl of will on the blank slate of the world …for all things come from work, from work and the kindnessof generous Gods. 3

In response to Virgil, we can imagine the contributors to this collection planting their seeds in the form of new critical ideas they have discovered in Eliot’s works.

***

As we celebrate George Eliot’s bicentennial birthday, November 22, 2019, we are led to ask how her fiction, that produced such witty and sensitive descriptions of her own era, can be read with profit and significance today: i.e., why proceed? Among numerous possible answers would be the following: we can read George Eliot’s works for her representations of cultural issues and values, for her keen discernment of interpersonal relations, and for her descriptions of private thought and motivation in lone individuals. Here, her masterful language produces rich meaning through metaphor , while her carefully wrought descriptions convey to readers previously unthought thoughts, fresh and far-reaching ideas. For example, Odile Boucher-Rivalain observes in her essay that George Eliot’s fictional and nonfictional works continually document the idea that “writing, unlike images by themselves, attunes us to the depth and height of perception in our lives. Are we silent about some things? We should think about them anyway. Then write about them. That is what George Eliot did.” If images commandeer our imaginations today with snapshots and videos that hover digitally across time and space, we are aware of the visual connections and knowledge we gain from them; however, we could also ask ourselves what we might be missing if we do not equally steep ourselves in the printed word that generates carefully considered and crafted ideas. Words on the page, such as Eliot read and wrote, enlarge a reader’s life experience and forge a depth of understanding such as no image alone can convey.

A History of Eliot’s Reader Reception

Victorian readers of George Eliot (1819–1890) led the way in appreciating her capacity to reach an exceptional level of human empathy through her writing. Recognized in her own time as one of the foremost writers of the British Victorian era—if not the foremost writer—her afterlife of fame and literary reputation tells an informative story about the ongoing culture of her readers. Toward the end of the British nineteenth century, the practice of writing fiction had evolved from a focus on realistic description as a method for finding truth in the observable world into a focus on aesthetics that could lead to significant beauty in literature as experienced by an individual. Realism’s external descriptions of the visible had yielded to aestheticism’s self -generated interpretations , and as a result, late Victorian reading preferences bypassed Eliot’s earlier realism . 4 In line with this reasoning, Aleksandra Budrewicz’s essay in this collection describes end-of-century writing as a tension between realism and aestheticism in British literature as it was exported to Poland. By 1895, fifteen years after Eliot’s passing, George Saintsbury wrote of this change: “though [Eliot] may still be read, she has more or less passed out of contemporary critical appreciation.” 5 Yet Eliot’s later development of internal sense experience is described by Sally Shuttleworth who claims that, with the rise of organic science studies,

the convention of realism … shifted: the task of the novelist, like that of the scientist, was no longer merely to name the visible order of the world. George Eliot’s fiction encapsulates these changes, foreshadowing subsequent developments in the Victorian novel. 6

Then, in the early twentieth century, the culture became embroiled in two all-consuming world wars, leading to some critical assessments of Eliot’s writing as not actually valuable as a contemporary representation of cultural life: in literature, Henry James, for example, described Eliot’s fiction as “a moralized fable.” 7 World War I, the decade of the 1920s, and World War II were reason enough for Europeans, Americans, and all readers of English to doubt that questions concerning conventional Victorian morality as represented by George Eliot, or the later study of aesthetics in literature, could be relevant to the chaos that was tearing their societies apart.

A Mid-Twentieth-Century Memoir by Thomas Pinney

To gain some insight into Eliot’s reception in the postwar years of the twentieth century, we turn to Thomas Pinney, who edited and published Essays of George Eliot in 1963. Because of his combined personal and public history touching upon George Eliot’s reception in the English-speaking world, first as a graduate student, and then as an English professor and editor, Pinney occupies an authoritative position to offer a memoir of Eliot’s reception history in the postwar period.

***

“George Eliot, Then and Now” 8by Thomas Pinney

At some time in the 1940s, I, and many thousands of other middle-school students across the country, read Silas Marner . The year before we had all read Ivanhoe, and in the next year, we would all read A Tale of Two Cities. 9 I don’t remember anything of my response to Silas Marner ; it was simply another book that one read because it was assigned. But being made required reading can be the kiss of death, and so it was, I think, for George Eliot. We had been exposed to her work too early for most of us, and a reaction of indifference set in. That indifference was confirmed by the change in literary taste that had come about after World War I. In college, we read nothing of George Eliot’s, and I do not remember that I ever even heard her name mentioned in four years of classes. Our teachers apparently shared our indifference. Dickens, yes; Hardy, yes; Trollope, maybe; George Eliot? Who? She was not even an also-ran.

That all changed when I was a graduate student, in the mid-1950s. In my first year at Yale , I signed up for Gordon Haight’s course in the English novel. Middlemarch was one of the assigned texts, and I still remember clearly my growing excitement as I made my delighted way through the book. It was a marvelous discovery and at the same time a mystery: Why, after my too-early encounter with Silas Marner , had I heard nothing further about this powerful writer?

The simple answer to that question was that George Eliot was then, and had been for some years, quite out of fashion. E. M. Forster called her novels “shapeless”; Lord David Cecil found her “provincial.” Almost everyone agreed that she was...