An organization’s health and its capacity to perform are critical for its survival. As a research subject, an organization’s health is a state or condition potentially affecting its ability to meet stakeholder needs, to handle adversity or to adapt to changing situations. But for the organization’s stakeholders, it is more than a representation or portrayal of the organization’s fitness or well-being. Stakeholders use an organization’s health as a personally meaningful standard for judging how well their needs will be met.

Stakeholders make multiple investments into the organizations of which they are a part. Sometimes, the investment is emotional, like the embrace in one’s religion, school or sports team. These relationships are often very personal and typically the product of an individual’s particular needs or values. Other times, the investment is more mundane, like the relationship one has with a job or his or her doctor. These are functional relationships; they make a contribution to one’s life, but the bonds maintained here are often discrete, sometimes marked by specific boundaries or limits. When a need is met, say through a purchase, the relationship breaks off … until next time.

Whatever the nature of the relationship, when the organization fails to perform or function in ways that meet stakeholder needs, the organization’s value to the stakeholder declines, sometimes even ends. Organizations suffering from the strain of a crisis, hampered by ill-prepared management and staff, or generally drifting because of poorly defined vision, policies or procedures are representative of dysfunctional organizations. In these instances, the stakeholder may not know who’s responsible for the poor performance, just that specific needs aren’t being met.

The relationship a stakeholder has with an organization’s brand is different. Brands are the personification of an organization to its public, to the organization’s stakeholders. The brand becomes the identifiable, portable, meaningful embodiment of an organization for a stakeholder. For each stakeholder in an organization’s social network, the brand image is the organization for that person. Now some may say this is an unrealistic, unreasonable way to characterize a stakeholder’s relationship with an organization, but for many stakeholders, it is the only way they know, or feel, they can make what’s global, impersonal or distant to them, real. And what this means is that while one might begin to think brand trauma is a condition the traumatized organization experiences, in reality brand trauma is a phenomenon both the organization and the organization’s stakeholders experience, and in their own, personal, meaningful way.

Diagnosing and Treating Organizational and Brand Trauma

Clearly, the trauma an organization experiences and the trauma associated with its brand are related. But addressing both, or treating both, requires different approaches. These two traumatic states are meaningful, but they are also inherently different. An organization facing a potentially threatening crisis, one threatening both its image and its very existence, is about to experience “organizational trauma.” When the brand is in a state of distress, we call that “brand trauma.”

To fully understand the nature and effects of organizational and brand trauma, it’s necessary to explore an organization’s health across a spectrum. Using a spectrum, in this case ranging from good health to those that are in poor health, provides a guide for gauging the health and well-being of both organizations and brands, as well as how trauma differs across both. More importantly, this analysis allows the stipulation and examination of factors that contribute to organizational and brand health generally. This is particularly useful information when attempting to restore traumatized organizations and brands to good health.

As one delves into the analysis of organization and brand health, a theme that becomes of particular interest are the effects on an organization, brand and stakeholders resulting from leadership. We explore implications of leadership on organizations, crises, brands and stakeholders from a variety of perspectives, but two are of special interest. First is the damage caused by leaders and their careless, sometimes intentional, behavior. Consider the subject reviewed in an article entitled “PR agencies develop ‘Trump strategies’” (Warc.com, 2017).

As written in the article, “President Trump’s propensity for tweeting about anything from developments in reality TV to criticisms of specific companies and brands is leading to a surge in a new business area for PR agencies.” “‘This is the first situation like this we’ve ever seen,’ according to Gene Grabowski, partner at crisis communication firm, KGlobal. ‘This is the first time clients [have] reached out asking, ‘What do we do if the president attacks us?’ … he told the Wall Street Journal.” It’s a leadership issue. But in this instance, an organization’s potential exposure to brand trauma may have little to do with what it has done and more with what someone in a position of power or authority says about it or expects it to do—or else.

The second leadership issue is one related to a number of cases explored in the book. In this instance, the piece by Mark Ritson (2017), in a recent issue of Marketing Week, illustrates the point. In the article, Ritson introduces his main point this way: “Everywhere you look these days you can find definitions, articles and whole speeches about what it takes to lead. Leaders are empathetic. Leaders are disruptive. Leadership means being agile. Leadership means staying fixed on one path. Leaders are this. But they are also that. Blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.”

We agree. In fact, we devote special attention to an organization’s leadership in Chap. 7. For now, however, what makes Ritson’s article of interest to us and the point that directly bears on our discussion of organizations and brand trauma are his comments regarding the extent to which leaders do or don’t demonstrate leadership in practice, not theory. Ritson summarizes his position this way, “Let me add to this increasingly confusing and convoluted area with my own helpful definition. Leaders have to fucking lead. I define leading as making a decision, not changing it, and then getting it done.” The fit between our position and his is best illustrated with his concluding statement in the article. “Rather than wanking about worrying about empathy and inspiration and creating a brand purpose that looks groovy,” he writes, “the job of being a big brand leader is really much simpler than many would have you believe. Step one: make decisions. Step two: execute them. Step three: go back to step one.” Well, as you’ll see, there’s a lot of this approach illustrated throughout the book, but we would add one more element to Ritson’s model: “think.”

Watch the evening news, cruise the web, read this book and note how many times brand trauma, trauma experienced by an organization’s stakeholders is a product of decisions sans thought. I agree with Ritson’s assessment, given the United and Tesla he presents. Both illustrations are potential trauma-creating events, but leadership is more than merely making decisions. Supporting a decision with thinking and research can be done in a timely manner and, in the end, avoid the dangers associated with a “shoot from the hip” approach.

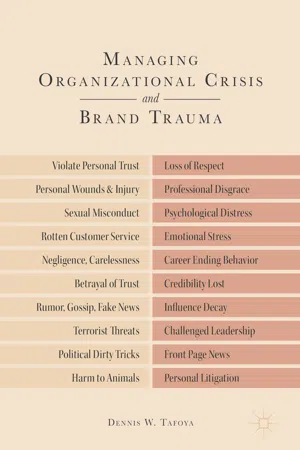

Trauma and brand trauma can strike at the heart of an organization and significantly affect every facet of its operations. No organization is immune. When people or organizations violate rules and regulations or put others at risk because of accidents, carelessness or negligence, not only injured stakeholders but an organization’s overall equilibrium can be challenged. An organization’s equilibrium is at risk because no accident or act is discrete or without effect. Events such as those listed above can stimulate ancillary conditions not originally associated with the initial event, and a thoughtless rush to “solve” a problem, to fix a crisis or to deal with complaints can trigger other accidents, can reveal bias or favoritism, lead to unfair treatment of employees or stakeholders and create general risk to the quality and safety of products or services.

Distinguishing between organizational and brand trauma is important for another reason. Sometimes, it is possible for the unhealthy organization to keep external stakeholders from exposure to its internal problems or conditions. Volkswagen had a need to make sure the cars it sold could pass pollution emission tests, so it came up with a novel, albeit illegal solution to meet its need. Hide devices in some cars so that they would pass emissions tests. Software that could recognize the test was being conducted and then could produce false data indicating a successful test. Wells Fargo also had an internal need to demonstrate powerful sales or new account creation data. Its solution also was simple. Just create fake accounts in their customers’ names and—voilà—great sales performance. Even the Catholic Church demonstrated its own range of creativity. When encountering allegations of sexual misconduct on the part of some priests, it actively covered up the actions of those involved, keeping the illicit behavior from the general public, investigators and, of course, its own membership. Each of these examples are important in their own right, but what makes them important from an organizational perspective is the way they illustrate how bad behavior can spawn more bad behavior and, in turn, put an organization’s brand at risk. Organizational trauma reflected in unacceptable behavior led to the emergence of brand trauma.

When illegal or undesirable behaviors become public, the effects on the crisis facing the organization take on a new dimension. On the inside, a crisis affects an organization long before it becomes known. Employees involved literally find that expectations associated with their jobs or work they were expected to do have changed to meet the increasing demands of the crisis. Those caught up in these cover-ups, for example, now may have been expected to lie, to misinform or just not disclose any aspect of the organization’s behavior to others. They didn’t hire on to engage in these behavior. Sometimes, involvement may extend beyond just “not talking about what you know or have seen.” They may even be expected to participate in creating or maintaining the conspiracy then becoming unwilling accomplices or partners in the crime, perhaps just to save their jobs.

Once public, however, both the organization and its brand can be trapped in the crisis, threatening the organization’s very existence and, given our focus, can trigger potentially dangerous brand trauma. Consider the fast-food restaurant’s operations and brand. News of poor food preparation or handling associated with weak or inappropriate operational policies and procedures and that has been associated with an outbreak of illness can trigger negative stakeholder responses. Stakeholders inside the organization must find causes to the problem and prepare and test solutions to prevent an event (e.g., food poisoning) from turning into a wide-scale crisis. Meanwhile, those outside of the organization also might change their behavior regarding the organization. Plans to eat at the restaurant are dropped, litigators look for information that might contribute to legal actions against the restaurant and regulators might schedule and launch investigations of the restaurant’s food preparation processes and materials. At this point, what was a largely internal matter with limited effects on the organization is now also a public matter tugging at the organization’s brand and image.

Society is filled with examples of an organization’s broken operations triggering potential brand crises. Rude behavior associated with a routine order-taking transaction in a fast-food restaurant and a police officer’s overly aggressive or prejudicial behavior associated with a routine traffic stop are now all-too-familiar examples. Whether we experience them directly or indirectly via television or social media, we use this information to evaluate what happened and, in turn, the organization or individual involved.

Brand trauma can be so powerful that it may even threaten relationships with organizations that are based on personal, emotional or sentimental bonds. Politics and religion are among an individual’s most private organizational relationships, some often associated with our families and linked to us from our earliest years. But when the sexual behavior or errant infidelities of our favorite politician or parish priest are revealed, our impressions can challenge us to reevaluate our feelings toward them. In these instances, our needs or a sacred trust is violated for them, but it’s their brands that are traumatized.

Some measure of trauma is associated with every crisis. Trauma, to paraphrase the definition of trauma appearing in Wiktionary.org, refers to any serious injury or emotional wound to an organization, often resulting from violence or an accident or event that leads to psychological injury or great distress (https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/trauma#English). As far as an organization’s brand is concerned, when expected events don’t unfold in a typical, sometimes mundane but familiar pattern, brand trauma can emerge.

Brand trauma parallels the trauma definition presented above, but brand trauma is unique because its emergence is more a product of the stakeholders affiliated with the organization and its social network than the crisis or event triggering it. Brand trauma is a communication phenomenon; when brand trauma emerges, it communicates something about the brand and about the ways people are thinking and talking about the brand. When a crisis occurs, the organization’s leadership may have to contend with two different traumatic conditions: one affecting the organization and its people and processes, and the other affecting the image stakeholders have created. Neglecting either can be catastrophic.

Finally, this is not to suggest that there’s either a causal or a linear relationship between organizational and brand trauma. A minor or routine event may not contribute to organizational trauma but mismanagement of the same may trigger brand trauma. Just imagine how you feel when you’re in a fast-food restaurant and the attendant is slow or rude! Your sentiments for that restaurant are channeled directly along your relationship with the organization—its brand. You may not know who owns McDonald’s or who is president of Burger King, but you do know you may not shop again at the restaurant where you received poor service!

Again, this isn’t to suggest that organizational and brand trauma can’t be linked. Rampant brand trauma if unchecked can lead to significant organizational trauma. Organizational trauma can often be addressed directly, by tackling the people, processes, materials, equipment or culture that’s defective. Brand trauma’s link to the organization’s stakeholders means that remedies rest with them; those affected stakeholders must change or reevaluate their impressions of the organization. So, while the organization’s leadership has to act as brand trauma emerges, it’s up to the stakeholders to determine if any treatment is sufficient. In the long term, of all the traumas an organization can experience, brand trauma has the greatest potential for harm.

The Nature of Brand Trauma and Its Effects on an Organization

This book will provide three benefits for the reader. First, it describes the ways a crisis is part of everyday life. A number of different crises are described across a variety of organizations or groups. Most will be familiar to the reader, so identifying with those involved should be straightforward. Second, the ways in which brand trauma emerges, matures and affects organizations is an especially important topic covered. This will help the reader understand different phases in the development process and, importantly, how and why those phases may vary among different types of organizations.

Finally, tools introduced for use in quantifying different elements of the model described above may be potentially enriching for the book’s readers. For example, researchers in the natural and social sciences may find our models outlining the emergence of brand trauma across different types of organizations or in response to different types of problems or situations a useful addition to what we know about the ways a crisis impacts organizations and their stakeholders. In addition, our methods for documenting and measuring diffusion and spread of trauma’s effects are particularly unique.

The emergence of trauma is a dramatic process, with effects that can unfold in different ways for different stakeholders. For example, in our treatment of the stakeholder swarm, a phenomenon which occurs when an emerging crisis stimulates the interests of different stakeholders, it becomes easier to explain how mob or crowd behavior can emerge. In these instances, stakeholders in the swarm may find that by simply acting on their own to express dissatisfaction with an organization behavior, they share a common bond with a variety of others.

Participating in a stakeholder swarm can bring people from all walks of life together on a common mission. They can find themselves standing and perhaps even partnering with others whom they wouldn’t normally acknowledge as sharing the same values, needs, interests and desires. Swarms can engulf the target organization with such a diverse group of participants that no single strategy to meet the swarm’s needs is possible. The affected organization must divvy its resources and attention among a number of different swarm members while always being careful that different messages sent to appease one and promises made to another don’t become common knowledge. Then cries of hypocrisy and duplicity can add to the flames of distrust encumbering the target organization. Now, in addition to a crisis that’s out of control, the organization’s membership slips into a pool of bureaucratic entanglements so that attention to fundamental day-to-da...