One of the few things that Gwyneth Murray and Harry Logan were able to agree upon was that a biography of them would be difficult to write. In response to Harry’s observation that biographers would come to grief in trying to reconcile their intimate selves, Gwyneth averred: “Yes our biographer will have a very difficult task but what an exceptionally interesting one it will be! Two such wonderful people as you and me to biograph!!”1 This, however, is not a biography in the conventional sense of narrating an entire life course; rather, it is a biography of a relationship,2 a microstudy of subjective attitudes to sexual love and their intersection with Edwardian culture.

Like the modernist novel , this book ventures directly into the flow of the relationship of this young couple, and explores letters which recount mundane everyday states of mind which have no fixed beginning and no resolved endings.3 By exploring the complexities, tensions and gender conflicts inherent in modern courtship and marriage as told through the story of the romance of Dardanella and Peter, this book offers one of the first sustained treatments of how heterosexual identities were both articulated and contested in early twentieth-century Britain. This book continues a scholarly conversation launched by William Reddy, which interprets attitudes to sexual desire and romantic love as historically contingent, and shows how these two entities, viewed as dichotomous for centuries,4 were brought into closer proximity as seen through the lived experience of a young married couple. In using the remarkably frank and emotionally charged correspondence of Gwyneth Murray, the youngest daughter of Sir James Murray , the famous editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, and her fiancé Harry Logan, an aspiring clergyman from Canada, it seeks to uncover the ways in which the language of love changed between the Victorian era and the Edwardian age. In assessing how the coded language of religion gave way to explicit sex talk, our study contributes to furthering our understanding of how sexual love became culturally central as Britain entered World War I.5

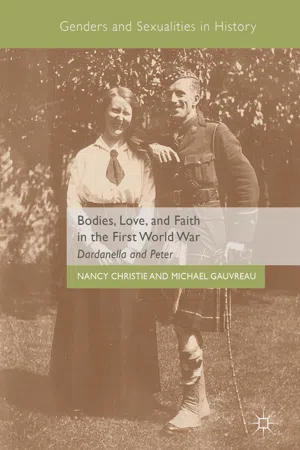

This is a book about the courtship and marriage of an Edwardian couple who wrote in the persona of their vagina (Dardanella) and penis (Peter) during World War I. From the first stirrings of sexual lust in 1911, when Peter began to imagine Dardanella’s erotic body while advising about weight loss, to the more explicit sex-talk about her vagina, breasts, nipples, pubic hair and marble limbs following their marriage in 1916, this aspiring clergyman and his British fiancée sought to develop a modern language of love and erotic desire which threw off Victorian moral sensibilities in favour of a more open mode of expression that evoked the pleasures of sex. Their correspondence spanned an era bracketed by Virginia Woolf’s celebrated aphorism that “human character changed on or about December 1910”6 and the publication of Lytton Strachey’s famous psychological study Eminent Victorians. The couple avidly read Strachey because it encapsulated their own journey of reflection and self-discovery and confirmed their personal break with the sexual mores and conventions of their parents’ generation. Because their first-person epistolary discussion of their courtship and marriage paralleled those broader cultural developments within the Edwardian temperament, usually encompassed under the term “modern”, their personal experience serves as a critical vantage point from which to assess how Edwardian culture was read, appropriated and lived by ordinary men and women of the middle classes.

The idea for writing Dardanella and Peter began with the following question: how did the experience of higher education for women affect the gender dynamics of courtship and marriage in the first decades of the twentieth century? The marvellous “archive of feeling”7 generated by the extensive correspondence of Harry and Gwyneth was discovered by Nancy Christie in the winter of 2014. As a scholar of the Victorian family, her curiosity was piqued when she encountered Harry’s first letter in which he was so obviously erotically fantasizing about Gwyneth’s entire body even as he cautioned her against getting fat. Christie immediately sensed an engagement with love and sex which was distinctly at odds with Victorian sensibilities which enjoined reticence and prurience about love and its relationship to the body. As she was to discover, Harry and Gwyneth first met while he was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford. Harry was a Canadian son of the manse and was himself aspiring to become a Presbyterian clergyman when he met Gwyneth who was a stellar student at Girton College, later achieving a coveted First in the Cambridge Maths Tripos. Like her mother and older sister Hilda, Gwyneth sympathized with the cause of women’s suffrage and believed in the intellectual equality of the sexes. Gwyneth was alive to new cultural stirrings, being drawn to the work of Henri Bergson and other exponents of vitalism, the new psychology and the new theology; as an amateur artist she was drawn to post-impressionism. Like many of her contemporaries at Girton, Gwyneth avidly read and discussed the sexually liberated Ann Veronica, the eponymous heroine of H.G. Wells ’ novel, and while she accepted the new feminism in which individual freedom for women was linked to greater sexual satisfaction, she rebuffed other symbols of female emancipation, such as shorter skirts and the jettisoning of restrictive corsets. However, she ultimately believed that women’s emancipation could be achieved through love and marriage, hoping that ideally she could combine these with a career.

Although she was known in her family circle for her shyness and reserve, she was always welcomed as a cheerful addition to the family because of her voluble humour and sense of fun. This is perhaps what first drew her to Harry, who was also known as a prankster, but who was more emotionally volatile in contrast to the confident and strong-minded Gwyneth. Harry was loquacious both in personal conversation and in his letter-writing, and as Gwyneth later related, upon his death in 1971, he was “chattering right up to the end”. He was later memorialized as a “prince among men” with a “secret mischievous grin”, usually holding a “cheerful cigar”. Although a Rhodes Scholar, he likely won the award because of his prowess on the track rather than for his academic accomplishments. However, when we first meet him he was puritanical and priggish, especially on issues of intemperance and sexual excess, as one might expect from someone raised in a strict Presbyterian home and ambitious for a clerical career. Harry presented himself in his correspondence as boisterous in personality, but he was also given to much introspection and bouts of depression, caused in part by the great pressure to succeed imposed upon him by his demanding father. The fact that he had a stutter may also have contributed to the lack of confidence and maturity which were self-evident during his courtship with Gwyneth. He was demanding and paternalistic in his attitude towards women, persistently picturing his fiancée as a sympathetic helpmeet, much like his mother, despite Gwyneth’s demand that she be treated like a real human being with her own needs.

Gwyneth and Harry may have shared a family background in evangelical Protestantism, which led to an ideal of religious service in missionary work, but in other respects their families were poles apart. Gwyneth was the youngest of eleven children from a prestigious Oxford family and remained emotionally distant not only from her parents but from her siblings, attributing her undemonstrative nature to the English public schools. Indeed, she revelled in her reserve as a sign of her rebellion against the standard image of the hysterical woman. By contrast, Harry was the younger of two brothers, and possessed a particularly intense bond with his indulgent mother. However, he also seemed to enjoy what he termed a “teasing” relationship with his father, whom he both admired and resented because he wished Harry to replicate his own career. Although Harry was raised in a well-known Presbyterian family in Vancouver, he was attracted to marrying into the Murray family for its prospects of upward mobility, but he nevertheless remained painfully conscious of the status differential between them. However, for both Gwyneth and Harry, attending university was a transformative experience, exposing them to an exciting spectrum of new ideas and permitting them to enjoy the comradeship of a youthful peer group that functioned as a counterweight to familial constraints. To an unparalleled degree, Oxford and Cambridge symbolized freedom to choose their friends and ideas, and was remembered by both of them as the most memorable time of their lives.8

In 1911, Harry and Gwyneth became secretly engaged but it was a courtship that remained a long-distance one until they married in the spring of 1916, when Harry, an officer in the Canadian Machine Gun Corps, was posted to the Western Front. As a result, their personal archive contains over 2000 letters written daily between 1911 and 1919, providing an unrivalled account of the psychological and emotional dimension of courtship and marriage in the Edwardian era. In so far as their correspondence involved a remarkably self-conscious engagement with a wide spectrum of emotions, including sexual desire, anxiety, frustration, anger and even shattered nerves, the letters of these two ordinary middle-class youth coming of age in Edwardian Britain are comparable to the vividness and psychological immediacy of those exchanged between Sigmund Freud and Martha Bernays during their own lengthy courtship, a correspondence characterized as among the great love literature of the world.9 Although the sexually explicit wartime letters are compelling in terms of what they convey about male and female sexuality within marriage, the courtship letters are no less interesting for the ways in which they...