In a post-9/11 world 1 and during an American Presidency that is deeply dependent on social media representations such as those on Twitter while at the same time established journalistic resources are discredited as “fake news,” it is important to discuss the influence of image-making on public awareness and the making of memory, especially concerning warfare. Younger generations, particularly in the West, learn about war entirely via mass media and are seldom taught the skills to analyze those sources critically, leading to distorted views of combat and the realities of war. 2 Often those who actually fight the battles are left out of the official reports as well as the fictionalized memoirs as can be seen in Zachary Michael Powell’s final chapter on the making of Dunkirk (2017) about World War II in this collection.

Films and television series play a large part in making the world outside one’s private confines and image consumption more accessible. Our book attempts to expand this view and memory of war: in New Perspectives on the War Film , our authors concentrate on the untold stories of those who fought in wars and were affected by the brutal consequences. The chapters span a wide variety of topics and different twentieth- and twenty-first-century wars. Among the leading themes we discuss are the representation of African-Americans, child soldiers and warlords , Indigenous peoples, homosexuality and gender relations in silent cinema, international terrorist wars, biological terrorism, women in war zones, as well as colonial subjects at the front who are left out in the mainstream depictions of heroism and white masculinity. By presenting such a vast and varying perspective on the war film, our co-edited volume attempts to close several gaps in the understanding of war representations in global mass media.

Images of war, global disasters and conflict, bombings, terrorist attacks, flooding, environmental carnage, and hunger surface on social media platforms almost daily with gut-wrenching imagery. Facebook is employing “cleaners” outside the United States who make sure that none of the pictures are too disturbing, blocking and censoring content. 3 Two years ago, one of the Pulitzer prize-winning images of the Vietnam War with a naked young girl running down the street after a Napalm bombing was deemed indecent and removed. 4 Although social media sites are credited with having helped to mobilize followers to protest and resist authoritarian government rules in the context of the Arab Spring in North Africa in the early twenty-first century, wars have not yet been officially declared over social media platforms.

Social media carry more and more responsibility to not cater to extremists who revel in carnage but to also control image-making of war. Most consumers scroll down their feeds and click “like,” “share” the posting with their “friends,” or ignore the displayed misery and devastation while concentrating on cat videos or cute family pictures. Our book seeks to contribute in telling stories about war that would otherwise not be visible. 5

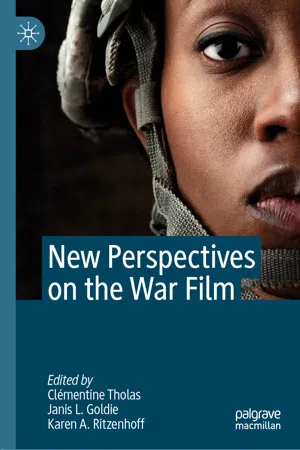

Choosing Our Cover Image

The face of a black woman soldier on our book cover is cut in half. She is only partially visible. Her helmet and camouflage attire signal that she might be in active combat. The woman looks directly at the camera, engaging the viewer. She does not smile. The background does not give any hints where she is from or where she might be deployed. It is a stock image from Getty. We could have chosen the same model with her head and helmet filling the entire frame. However, our idea for the scope of this book on New Perspectives on the War Film is to demonstrate how members of minority groups such as colonial armies during World War II at Dunkirk, Indigenous peoples in Canada, African-American soldiers, women and children have been written out of the script of mainstream blockbuster narratives about war.

Our consensus to use the photograph that shows only a partial view of the female soldier was based on the idea that representations of women in war film, even in documentaries, are over truncated and incomplete. In Lioness (2008), for example, the first team of female American soldiers who were deployed in Iraq in 2003 as support for their male ground forces end up in active combat. One scene in the documentary shows the female veterans sharing an afternoon together and watching a History Channel feature about the ambush in Fallujah. The report does not mention that women were there in active combat but only praises the brave men who were there.

In January 2013, the US Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta allowed women in the battlefield and front lines officially for the first time. 6 Of course, nurses and female soldiers have been there all along, but not officially. However only in 2016 did women have the choice to decide what kind of service and military specialty they wanted to serve in. Meanwhile, the American military is reverting civil rights for transgender and homosexual soldiers who have been accepted for military service in the era of President Barack Obama who removed the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. It is this absence of representation both in the actual theater of war and on screen that this volume seeks to address. In particular, some chapters address not only homosexuality in World War I (see Clémentine Tholas) but also the role of women in the military (see Chapter 3 by Liz Clarke).

Origins of the War Film

The war film genre has been inextricably associated with Hollywood for many decades and has directly and indirectly participated in the dialectics of foreign affairs. The first question we can ask is: which film was the first war film? The thirty-second single shot Tearing Down the Spanish Flag (1898) is often evoked as the original and one should not forget that several films dealing with historical wars (Revolutionary War, Civil War ) were in fashion by the 1910s and provided American audiences with visions of history and touches of patriotism. In Europe, films dealing with the Antiquity and its epic battles served the same purpose. The war belonged then to a distant as well as a recent past and its cinematic evocations contributed to the creation of local mythologies and/or to commenting and analyzing history itself. When World War I started, films and war films in particular took on another role: for the first time ever, the contemporary war was directly brought in front of the eyes of people. Non-fighters were psychologically mobilized because they had a visual access to some of the realities of the confrontation. Films also served as major contributors to the circulation of Americanism around the world.

In 2014, the San Francisco Film Festival displayed the slogan “1917: the year that changed the movies.” 7 1917 can also be understood as the year that changed the US relationships with other countries with the help of its national cinema. According to journalist Stuart Klawans, the impact of the war was not only ideological but also technical and aesthetic because the conflict transformed “the conditions of filmmaking” all over the world. He considers that “to a remarkable degree, today’s film industry retains the shape it was given by the war—which means that every picture we see is in some sense a World War I movie.” 8 American motion pictures became the dominant international form of entertainment and the war film took part in a larger system of state propaganda managed by the Committee on Public Information under the guidance of George Creel. Consequently, war films did not deal anymore with the past but with the present. Newsreels and entertainment films circulated genuine and fictionalized images of the conflict and were used as a way to influence national and international public opinions regarding the role of each country. American war films served the cause of President Woodrow Wilson’s moral diplomacy which aimed at portraying the United States as uncontested champion of democratic values against barbarity and wrapped American interventionism in a cloak of morality.

Kevin Brownlow explains that as soon as the conflict was over, spectators—American spectators in particular—developed mixed feelings toward war films whose popularity plummeted. 9 In Europe and in the United States, virulent anti-war productions (re)appeared, with films like Abel Gance’s J’accuse (1919) and Rex Ingram’s The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) which denounced the conflict for being a gigantic manslaughter. This shift redefined the role of the war film as a means of disparaging armed conflicts and jingoism, only a few years after they were used to celebrate military might and patriotism. However, the 1920s were characterized by a sort of moral and ethical divide regarding war films due to the coexistence of anti-war films and nostalgic melodramas paying a tribute to a lost generation. This early division within the genre itself illustrates the original complexity and duality of the war film whose multifaceted approa...