In 1762, in a letter to the Archbishop of Paris, Jean Jacques Rousseau wrote: ‘If ever there was in the world a warranted and proven history, it is that of vampires’ (Rousseau in Masters 1975: 243). Rousseau’s statement goes on to cite testimonials, trials, and letters from persons of good standing; evidence, he concludes, that stakes a claim for the ‘proven’ prehistory of vampires and their extensive proliferation through oral history, folklore, and in the cultural imagination. Vampires, then, enable the living to refute and refuse the terrifying notion that death may be the end. In their allegorical afterlife, suffused with symbolic richness, vampires have become familiar emblems for capitalist exploitation, fear of the invading and unknowable ‘other’, and familiar representations of social and moral corruption: they are superb indicators and documenters of social anxiety and cultural change.

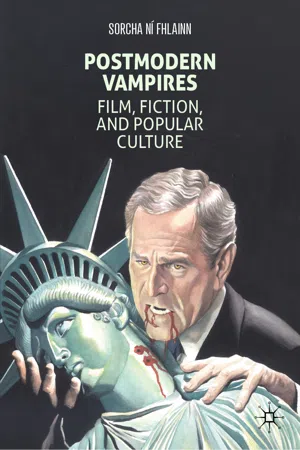

For me, the vampire’s point of view has always been tantalising; it promises access to secrets on the forbidden and the fantastic. In the early 1990s, a seemingly throwaway joke first primed my early desire to seek out such literature: In ‘The Otto Show’ (3. 22) of The Simpsons , school-bus driver and heavy metal enthusiast Otto Mann is evicted from his home and invited to stay with the dysfunctional yet lovable Simpson family. Perusing their sparse bookshelves, Otto enquires, ‘you got anything written from the vampire’s point of view?’ which is met with Marge Simpson’s signature disapproval. Such a seemingly flippant remark subtly acknowledges the widespread use of vampiric subjectivity, even if, as suggested in the 1992 episode, it is only set up as a joke to be dismissed; only Otto, an uneducated metal-head, would find something worthy in such literature. Nevertheless, it left an indelible mark in my imagination. In 1994, another pivotal biographical moment came: Irish director Neil Jordan helmed the difficult task of bringing Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire to the screen. This was my personal teenage gateway to vampire texts beyond Stoker’s Dracula: Its opening scene celebrated the vampire’s subjectivity as a marvel and an invitation—‘So you want me to tell you the story of my life?’ said Louis (Brad Pitt)—promising to disclose secrets and Gothic wonders. Opening up this rich vein in fiction and film, I began to see patterns in their metamorphosis, and how vampirism is a powerful and malleable Gothic signifier for a myriad of social and political discourses. In 2008, in the True Blood episode, ‘Escape from Dragon House’ (1.4), Alex Ross’s painting ‘Sucking Democracy Dry’, an arresting image of protest against the Patriot Act (2001) (and the most apt cover I could ever conceive of having for this book), featured behind the bar at the vampire establishment Fangtasia . The camera playfully paused over it for a mere second, enough time to register it as a wry acknowledgement that, for Ross , the presidency and vampirism had undoubtedly merged allegorically, if not literally, in his imagination and had now found a suitable place in the mise-en-scène of this exciting HBO series. This image overtly declares vampirism has spread from the margins of society to the centre of power in the twenty-first century, consolidated in the timeliness of Ross’s powerful art; Ross expressed what scholars including myself had, by this time, previously documented in our works, but this moment brought it together in spectacular fashion. These small but powerful moments offer a glimpse in understanding the irresistible power of the vampire in film, popular fiction, and popular culture.

Of course, vampires in the American imagination come to the New World by means of mass communication; products of books and films, television, and domestic infiltration, they find American culture a suitable place to advance their evolution . They transcend their long nineteenth-century archetype as aristocrats and Counts and find their place among the everyday American experience—in bars and small towns, and as neighbours, friends, protectors, and leaders. For these exemplary subjective vampires unleashed into the late twentieth century, the period of Postmodernity, of eroding certainty and voicing scepticism, offers spectacular potential. As Nina Auerbach sagely observed in the mid-1990s, ‘vampires go where power is’ (Auerbach 1995: 6). This book is certainly inspired by Auerbach’s superb and sage vampire scholarship, but also vastly extends this allegorical observation by examining the Postmodern aspect of undeath since the late 1960s in the American imagination, and explores the extent to which it finds cultural catharsis in literature, film, and American popular culture.

Before 1968, subjective vampires led a marginalised, and often mute, existence. Vampires were foreign ‘others’, archaic Gothic intruders perpetually symbolising the past, and arrested in their nineteenth-century framework as intruders at the margins of the American century. Previously represented through the vampire hunter’s narrative as one dimensional (and often solitary) beings that must be obliterated, vampires began to turn on those who wield such narrative authority, determined to claim their own undead experience on their own terms. Without the Postmodern turn, the vampire would have been relegated as a static if not ossified Gothic convention, reinforcing brittle associations with the past that are no longer relevant in the present. It is through this crucial development and identification of the vampire’s subjective voice within the horror genre that marks the vampire’s transition from modernity to Postmodernity in fiction and film.

Ellen E. Berry argues that ‘[t]he modernist idea of culture was generated out of a specific sense of cultural hierarchy that divided cultural spaces and products into highbrow (true culture) and lowbrow (popular culture)’ (Berry 1995:134). As a number of its most prominent theorists, from Eliot to Adorno, maintained, modernism can be defined by its antipathy to mass culture which ‘arouses “the cheapest emotional responses,”’ as ‘[f]ilms, newspapers, publicity in all forms, commercially-catered fiction – all offer satisfaction at the lowest level’ (Carey 1992: 7). Fredric Jameson , in his highly influential book Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991), separates the modern and the Postmodern very specifically, where ‘modernism thought of itself as a prodigious revolution in cultural production, however, Postmodernism thinks of itself as a renewal of production as such after a long period of ossification and dwelling among dead monuments’ (Jameson 1991: 313). Once considered such a nineteenth-century static ‘dead monument’, a sepulchre frozen in time, the undead are soon quickened and revitalised in this Postmodern climate. Jameson’s distinctions are essential if we are to understand the vampire narrative as a Postmodern development, as this new subjective insight essentially destroys the boundaries between us and the monsters we encounter, a distinction held by earlier distinguished vampire authors, most notably Bram Stoker; Postmodernism redefines and reshapes the narrative by providing a tantalising insight by the very creature that was previously marginalised. Stoker’s epistolary novel omits the voice of its own titular villain, a gap which vampires have been eager to fill since the 1970s, with authors such as Fred Saberhagan and Anne Rice championing their articulacy. Furthermore, Postmodernism rejects the sanctity of metanarratives or grand narratives, bringing forth a necessary scepticism towards such structures in an age that permits a fluid cultural blurring of these previously separate ideological frameworks. This collapsing of hierarchical structures—of high and low culture—allows for equal status, drawing together numerous strands of ‘textual’ production (as all modes of production can be read as textual entities—television, cinema, advertising, literature, new media, etc.) largely accessible and consumed in society. It denies determinist constructions or classifications of what is ‘art’ or ‘literature’ and breaks down aesthetic hierarchies:

The Postmodernisms have, in fact, been fascinated precisely by this whole ‘degraded’ landscape of schlock and kitsch, of TV series and Reader’s Digest culture, of advertising and motels, of the late show and the grade-B Hollywood film, of so-called paraliterature with its airport paperback categories of the Gothic and the romance, the popular biography, the murder mystery, and the science fiction or fantasy novel: materials they no longer simply ‘quote’, as a Joyce or a Mahler might have done, but incorporate into their very substance. (Jameson 1991: 3–4)

The Postmodernist shift in the vampire narrative stems from the breaking of a prolonged silence, or complete absence of subjective interiority in earlier narratives and cinematic representations. These exemplary subjective vampires form Postmodern ‘mini-narratives’, shifting in representation, political mockery, contingent upon the political moment, and largely localised within American culture. However, Postmodernism erodes old paradigms with the rapid rise of new technology and scientific discovery, consumerism, and cultural production. As David Harvey suggests, this new terrain includes ‘the re-emergence of concern in ethics, politics, and anthropology for the validity and dignity of “the other” leading to a ‘profound shift in “the structure of feeling”’ (1990: 9); breaking away from the ‘totality’ of grand narratives and dominant discourse, it enables New Historicist approaches in documenting cultural expression. Postmodernity presents a plural platform to foreground unheard voices, and apes other forms of established power in its playful bricolage; it upturns monstrosity as something recognisable and potentially sympathetic, allowing vampires and other creatures into our domestic lives, all the while presenting a reflection of the historical moment through a Gothic lens.

Towards Vampire Subjectivity: 1968–1975

Vampires have flourished in the popular imagination in particular since the early nineteenth century, but it was the publication of Dracula in 1897 that assured the vampire’s afterlife. In these earlier nineteenth and twentieth century tales, vampires must be kept outside our permeable social borders; so threatening in their ‘otherness’, they were pursued and finally vanquished in order to reassure and restore social norms by containing the threats they symbolise. Today vampires are among us, and in greater numbers than ever before. They are now our anti-heroes, our saviours, our protectors, our friends and lovers, and our storytellers. Since 1968, the advent of Postmodernism within American Studies, the commercial commodification of monsters bred a new form of vampire that capitalised upon the familiarity of Lugosi’s archetypical image in order to evolve beyond it. This new era of radical political upheaval and social questioning reinvigorated and remoulded a cultural monster that represented cyclical trappings of the past, which felt no longer relevant at the end of the 1960s. The late 1960s saw the end of the Hays Code (1930), the televised horrors of the War in Vietnam, and the rising tide of protest and counterculture, before the movement later soured into malaise by the early 1970s. During this transition from the 1960s into the early 1970s, vampires appeared in domestic American spaces— Dark Shadows (1966–1971) was broadcast on...