Introduction: The City Always Wins

In the first pages of his debut novel,

The City Always Wins (

2017), Omar Robert Hamilton describes Cairo, the city of the title, as an urban space ‘of infinite interminglings and unending metaphor’:

Cairo is jazz: all contrapuntal influence jostling for attention, occasionally brilliant solos standing high above the steady rhythm of the street. […] These streets laid out to echo the order and ratio and martial management of the modern city now moulded by the tireless rhythms of salesmen and hawkers and car horns and gas peddlers all out in ownership of their city, mixing pasts with their present, birthing a new now of south and north, young and old, country and city all combining and coming out loud and brash and with a beauty incomprehensible. Yes, Cairo is jazz. (2017: 10)

In this introductory passage and throughout the novel, Hamilton’s literary writing invites critical questions about the relationships between post/colonial urban infrastructures, literature and culture—questions that

this book’s central, organizing concept of ‘planned violence’ also sets out to explore. By way of introduction, the novel offers an emblematic window into our discussion of urban infrastructure and post/colonial resistance.

Beginning in Cairo ten months after the revolution of January 2011, the first section of Hamilton’s novel captures the heady period of urban resistance and democratic protest that centred on Tahrir Square, a huge public space in the heart of the city. In its second and third sections, however, the narrative turns to chart the suppression of this resistance, socially and spatially, by the Egyptian military’s use of planned infrastructures—barricades, roadblocks and barbed wire—designed to ‘zone’ and ‘confine’ protesters, ‘segregating them in limited spaces of war’ (Abaza 2013: 127). These planned infrastructures crush the revolutionary movement with which the novel opens, as state and private actors turn their militarized infrastructure and ‘weaponized architecture’ on their civilian populations (Graham 2011: xiii-xv; see also Lambert 2012). It is in this sense that the novel finds itself conceding that, in the end, ‘the city always wins’.

The City Always Wins raises some of the key questions that are taken up in the sixteen chapters and three creative pieces that constitute this edited collection, Planned Violence: Post/Colonial Urban Infrastructure, Literature and Culture. The contributors explore along a number of different vectors—metaphorical, linguistic, spatial and historical—how urban infrastructures make manifest social and cultural inequalities, and how art forms including literature can speak back to these often violent coordinates. In Hamilton’s opening description of Cairo, quoted above, the multiple layers of planned and unplanned urban life resemble the ricocheting notes of an improvised jazz score, suggesting something of the spontaneous effects and energies of everyday life as they play out over the underlying urban infrastructures that ‘order and ratio and martial’ city space. These are the ‘physical and spatial arrangements’ from which a society’s overarching values and prejudices can be read, and which, as Anthony King observes, are nowhere ‘more apparent than in the “colonial cities” of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, whether in Africa, Asia or middle America’ (1976: xii). Cairo’s urban development and spatial arrangements, forged during Britain’s occupation of Egypt from 1881, materialize this trajectory (see Mourad 2017: 22), as do the spaces of other cities examined in this collection: Johannesburg, Belfast, London, Delhi, New York and Oxford. As Frantz Fanon evocatively described in his account of the colonial city as ‘a world divided into compartments’, such segregationist infrastructural planning relied on ‘lines of force’ that brought ‘violence into the home and into the mind of the native’ (2001: 29). According to Fanon, urban planning in Algiers, as in Cairo and other colonial cities, was a violent materialization of colonialism’s exploitative project: it was a ‘planned violence’, as this book terms it.

In this passage, Hamilton also points to countervailing aspects, however, including the contingency of these rationalist, geometric planning regimes. Reinterpreting and reclaiming this planned space are the interventions of ordinary people, ‘the tireless rhythms of salesmen and hawkers and car horns and gas peddlers all out in ownership of their city’ (2017: 10). The array of informal social and economic activities that undercut and override the once-colonial city captures a different and more enabling notion of infrastructure, recalling Abdoumaliq Simone’s notion of ‘people as infrastructure’, a concept that ‘emphasizes economic collaboration among residents seemingly marginalized from and made miserable by urban life’ (2008: 68). Through such processes, urban dwellers might further enact a repossession of urban space, what Henri Lefebvre would describe as ‘the right to the city’ (2000: 147–159). In the physical, kinetic, aural and visual occupation of urban space, they lay claim to ‘some kind of shaping power over the processes of urbanisation’, demanding a participatory and democratic say ‘over the ways in which our cities are made and remade’ (Harvey 2012: 5).

That Hamilton couches even the informal activities of ‘hawkers’ and ‘peddlers’ in such overtly politicized terms sets the context of urban protest and counteractive planned violence, a contest that plays out in the novel’s fictional account of the Egyptian Revolution and its aftermath. The images of the huge public protests that took place in Tahrir Square in January 2011 have since become iconic symbols of urban resistance in the twenty-first century, as movements mobilizing against planned and other kinds of violence around the world concentrate very precisely on the reclamation of central, public urban spaces (see Franck and Huang 2012: 3–6). We think here of the occupiers of Gezi Park in Turkey, Catalunya Square in Barcelona and Zucotti Park in New York, all of which referenced Tahrir as a ‘transposable’ coordinate with which to foreground the political underpinnings of their causes (see Gregory 2013: 243; Castells 2012: 21). The ‘performance’ of the right to the city in Tahrir of course ‘depended on the prior existence of pavement, street, and square’, as Judith Butler notes, but, reciprocally, ‘it is equally true that the collective actions collect the space itself, gather the pavement, and animate and organize the architecture’ (2011: n.pag.). As this again suggests, resistance to privately funded or state-sanctioned ‘planned violence’ is grounded in its strategic reclamation of the physical urban infrastructures of the city. It is through that embodied occupation of physical space, or what Butler calls ‘bodies in alliance’, that the imaginative reconfiguration of alternative urban spaces and modes of city living might be generated. This is a process that Hamilton’s novel is itself concerned first to document and then to enact through its form, reconfiguring literary infrastructures as a resistant counterpoint to the planned violence of urban infrastructure, as we will see happen again and again across this book.

Though not concerned with such explicitly revolutionary urban movements, Rana Dasgupta’s Capital (2014), a love-hate song to Delhi and its singular brand of modernity—ribald, brutal, cacophonous, exhilarating—similarly represents the city as a place of embedded inequalities through its non-fictional yet literary form (a genre explored in more detail by Ankhi Mukherjee in Chap. 5 of this collection). For Dasgupta, the city’s divisions and layerings are cross-hatched with a globalized mass-culture born of post/colonial conflict, in this case the 1947 Partition. Meanwhile, interstitial subcultures also work to re-elaborate and reconstruct streets, markets and other spaces in ways that involve the city dwellers themselves. Imitating Dasgupta’s own movement through the city, the book’s mostly untitled chapters rocket the reader through a series of formative post-1991 Delhi experiences, from outsourcing and Americanization to corruption and the accumulation of waste. Chapters that dwell on formative moments in the city’s history are themselves threaded through with the author’s conversations with prototypical ‘Delhi-ites’, engaged varyingly along a spectrum of violent, corrupt and activist projects. By thus interspersing his movement through and stoppages in Delhi’s clogged motorway system with the individual stories of his interviewees, Dasgupta’s own writing sets about mapping the city’s chaotic street infrastructure while at the same time plotting intrepid individual routes through it, as indeed does Arundhati Roy’s more recent (2017) novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, taken up by Alex Tickell in Chap. 11 of this collection. In both cases, the infrastructures of literary form and genre speak to and move against the violent restrictions of urban infrastructures.

Or to take yet another example, the characters in Aminatta Forna’s The Memory of Love (2010), a novel about the 1990s Civil War in Sierra Leone and its aftermath, recall how the fearsome rebel army, or Revolutionary United Front, swept through the capital Freetown, targeting and destroying with overwhelming violence the infrastructures of city streets, bridges and government buildings, which to them functioned as oppressive symbols of colonial power. In the war’s aftermath the city becomes for characters like Kai, Forna’s protagonist, punctuated by painful no-go areas, the conflict lingering, embedded in his subjective psychogeography. Yet, while Forna charts these personal maps of urban trauma, at the same time her lucid, fast-moving prose explores life-affirming through-routes that the characters have managed to carve out in spite of the prevailing historical violence. These new urban pathways, built on preferred, often more circuitous walks and drives once made for pleasure, allow the reader to observe Kai and others repossessing imaginatively the city they inhabit. Through its mappings of these reroutings and alternative urban geographies, Forna’s novel builds a resistant literary infrastructure, one able to counter the city’s lingering planned and replanned violence.

In this collection, we take inspiration from creative works such as these to focus on the ways in which literary and cultural production is able to offer a critical purchase on planned violence, a concept we outline in more detail below. How does culture excavate, expose and challenge such violence? As importantly, we are interested in how these cultural forms contribute to more productive processes of social and infrastructural re-imagination and reconfiguration, and therefore also include three pieces of creative writing at the collection’s turning points. In these various ways we repeat and expand with respect to a range of cities the questions that cultural critic Sarah Nuttall asks specifically of Johannesburg: How does the post/colonial city ‘emerge as an idea and a form in contemporary literatures of the city?’ What are the ‘literary infrastructures’ that help to give the city imaginary shape? What forms can build ‘alternative city-spaces’ (2008: 195)? And finally, what are the ‘disruptive questions’ that literary texts ask of urban infrastructure, ‘including in actual practice, on the ground’ (Boehmer and Davies 2015: 397)?

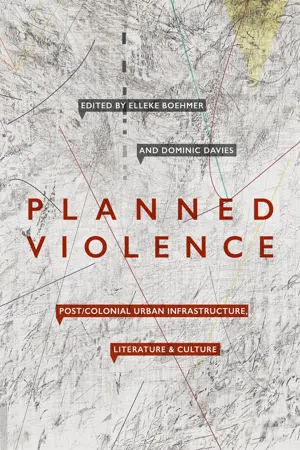

To begin to answer these questions, let us turn again to another powerful artistic response to revolutionary Cairo, one that operates alongside and in dialogue with Omar Robert Hamilton’s. Julie Mehretu’s ‘Mogamma, A Painting in Four Parts’ offers a visual reflection on the heterogeneous, layered explosion of planned and unplanned movement, and formal and informal infrastructures in Cairo—‘Part One’ of the series is reproduced on this book’s cover. As this shows, in Mehretu’s work the formally planned lines of the urban architect are disrupted by alternative topographical scales and shot through with erratic lines of flight. Through their bricolage-like assemblage, these lines capture a descriptive failure to interpret the utopian moment of the Egyptian Revolution, as Nicholas Simcik Arese also explores in Chap. 3. Indeed, this failure to decode Cairo’s revolutionary urban space returns us to Hamilton’s formal efforts to depict the city’s infra...