A record 65.3 million people were forcibly displaced in 2015 (UNHCR 2016). While the number of conflicts had been steadily declining for more than a decade, the last few years have witnessed a wave of new conflicts in the CAR, Mali, Libya , Syria , and Yemen . Old conflicts have reignited and new ones have erupted in Nigeria , South Sudan, Syria, and Ukraine, among others. The UN is struggling with a formidable range of threats—from more “traditional” protection threats in for example the CAR and in South Sudan, to violent extremism and terrorism in Mali.

The first decade of the new millennium was marked by a decrease in the number of state and non-state conflicts in the world, from 51 and 21 (respectively) in 1991, to 31 and 28 in 2010 (UCDP 2016), and evidence of UN peacekeeping contributing to lasting peace and development (Howard 2008; Fortna 2008). In recent years, the number of state and non-state conflicts has been on the increase again: in 2015 the Uppsala Conflict Data Program counted 71 state-based conflicts and 51 non-state conflicts in the world. These data suggest that force is increasingly perceived as the best tool to achieve policy goals and solve disputes, but the track record is poor. From Afghanistan , to Iraq, Libya , Mali, Nigeria , Somalia, Sudan, Syria , and Yemen , force has contributed to greater suffering, lasting and spreading instability, and refugee flows. With Syria and Ukraine, we may have returned to the proxy wars and zero-sum games of the Cold War, at least in some regions of the world.

In many fragile countries, the elite maintain power by buying allegiance from the potential opposition with the relatively few economic and military resources available. Kleptocratic leadership—in the case of South Sudan characterized as a “militarized, corrupt neo-patrimonial system of governance” (de Waal 2014: 347)—is the very source of fragility, leaving few if any resources for security, education, infrastructure, or social services. The “youth bulge ” facing the Southern Hemisphere, and Africa in particular, compounds these challenges. Over the next 15 years, 435 million young people will be searching for jobs in Africa, representing two-thirds of the global growth in the workforce worldwide (African Economic Outlook 2015: xii). Without future prospects, these young people may become involved in crime and violent politics, and be vulnerable to radicalization . Youth also form the bulk of migrants and refugees from Africa in Europe and elsewhere in Africa, fleeing conflict and seeking to support their families. Global remittance flows reached USD 440 billion in 2015 (World Bank 2015).

Youth also formed the core of the “Arab Spring,” which started in Tunisia and spread across the Arab world in 2011. However, this Arab Spring was short-lived—for a short while, the use of modern technologies and social media was hailed for leveling the playing field, but it did not take long before these technologies were turned into modern swords of Damocles against those who used them (Karlsrud 2014: 151). The use of modern technologies as a tool for intelligence-gathering on behalf of oppressive regimes was a key trend during the Arab Spring, often with the support of Western companies (ibid.; Elgin and Silver 2012; Wagner 2012). Terrorist groups have also showed their prowess in using the same tools for nefarious purposes. Today, many of the countries of the Arab Spring are embroiled in conflict and may tomorrow be hosting new peace operations deployed by the UN or by coalitions of the willing , regional or sub-regional organizations . Libya , Syria , and Yemen seem likely candidates here.

The challenges of violent extremism and terrorism figure prominently in discussions on the form and shape such future peace operations should take. Although political violence is an age-old phenomenon, and terrorism has long been high on the agenda, particularly since the 9/11 attacks in 2001, violent extremism and terrorism are now portrayed as “new” challenges, central to the ongoing debate on how UN peace operations can be reformed so as to be relevant to the challenges of the world today. The number of fatalities caused by terrorism globally has been rising steadily since 2000, from 3329 in 2000 to 32,685 in 2014 (IEP 2015: 2). A particularly dramatic increase came in 2014, up by 80% compared to 2013, largely because of the so-called IS and Boko Haram (ibid.). Not only have the numbers of victims increased exponentially over the last decade or so, the acts committed by terrorist groups are increasingly aimed at shocking the conscience of humanity. Many constitute war crimes and crimes against humanity (see, e.g., UNHRC 2015). Key groups behind terrorist attacks include al-Qaeda (e.g., Afghanistan , Iraq, and Syria ), IS (e.g., Syria and Iraq), Boko Haram (Nigeria , Cameroon , Niger , and Chad ), al-Shabaab (Somalia), Ansar Dine (Mali), al-Mourabitoun (Mali), and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) (Mali).

The shockingly violent acts—largely against civilians and often deliberately targeting women—committed by groups like IS and Boko Haram, with rape, sexual slavery, and forced marriage used as terror tactics (UN 2015b), have made it more urgent to deal with these rapidly growing threats. Violent extremism, and the militarization of societies that follows security-oriented approaches to fighting violent extremism and terrorism, has “an adverse effect on women’s security” (Stamnes and Osland 2016: 17), placing women “between this rising tide of violent extremism in their societies and the constraints placed on their work by counter-terrorism policies that restrict their access to critical funds and resources” (UN 2015c: 224). Violent extremism, terrorism, and counter-terrorism put vulnerable groups between a rock and a hard place, narrowing the space for engagement by women peacebuilders and limiting the funding for basic services and peacebuilding activities.

Since 9/11, also the UN has increasingly become the target of terrorist attacks. The attacks in Baghdad in 2003, Algiers in 2007, Kabul in 2009, Mazar-i-Sharif in 2011, Abuja in 2011, Mogadishu in 2013, and several attacks in Mali from 2013 to today, in addition to a great many smaller attacks, have all made it increasingly clear that in many places the UN is not seen as an impartial actor, but rather a participant in the global war on terror. In turn, the UN has adjusted its risk posture by taking precautions on movement and deployment of staff in high-risk zones and bunkerizing itself behind high walls and red-tape risk procedures, increasing the distance with the local populations that the organization is meant to serve (see, e.g., Duffield 2012).

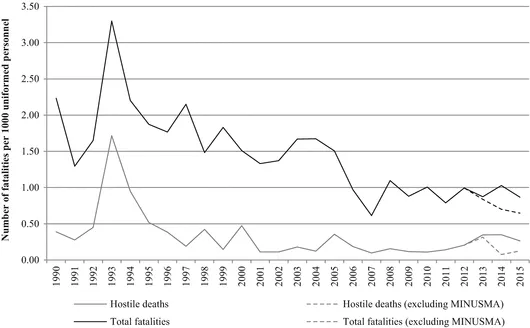

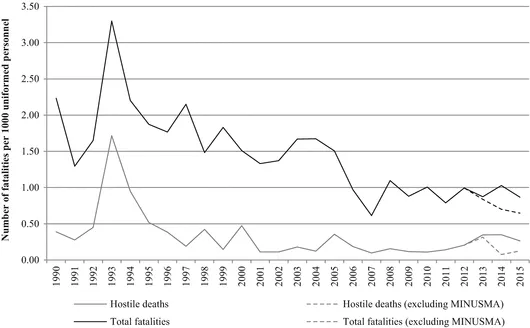

On the other hand, the impression that the UN is increasingly being targeted and is losing more people to hostile attacks now than before deserves further scrutiny. In 2014, UN peace operations suffered 126 fatalities, 39 of which due to hostile acts, most of them in

Mali (UN

2016b). A study by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) found that while this was a high number, fatality ratios

—as measured against the total number of troops, police, and civilians deployed in the field—have remained fairly steady at about 1 per 1000 since 2008 (van der Lijn and Smit

2015). In comparison, the fatality ratio between 1990 and 2005 was more than 1.5 (peaking at 3.3 in 1993), then showing a significant decrease from about 1.7 to less than 1 between 2005 and 2007 (ibid.; see also Henke

2017). In recent years, MINUSMA has added the toll—it has become the deadliest of current UN peacekeeping operations accounting for 40 out of a total of 60 fatalities caused by malicious acts in 2014–2015 alone (ibid.; UN

2016a), with a fatality rate of 2.38 (van der Lijn and Smit

2015: 7).

1 But Mali, as discussed later, is not an ordinary peacekeeping mission, and if Mali is subtracted from the overall fatality count, “2014 actually had the fewest hostile deaths per 1000 since 1990 (0.08 per 1000)” (ibid.: 3) (Fig.

1.1).

The UN is currently in a state of flux when it comes to developing policy on counter-terrorism and countering and preventing violent extremism, with increasing pressure from some member states for the UN to take on a greater share of these challenges. Member states and multilateral organizations have developed various doctrines and guidelines for countering and preventing violent extremism, from military-oriented counter-insurgency to counter-terrorism guidance, such as the US Counterinsurgency Field Manual and NATO ’s Military Concept for Defence Against Terrorism (United States Dept. of the Army and United States Marine Corps 2007; NATO 2011). In December 2015, the SG presented a new Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism , emphasizing the need to focus on the preventive aspect (2015d).

The heightened attention to the threat of violent extremism and terrorism has come in an environment of economic austerity and fatigue of Western troops after 15 years of warfare in Afghanistan and Iraq. It has been followed by promptings from the USA and other Western powers for the UN to take greater responsibility for the challenges facing the international community. With the increasing pressure on the UN to reform UN peace operations to be relevant to these tasks, it is pertinent to ask: should the UN update its principles and practices to a new context—or are existing principles and practices still valid?

This chapter assesses the role of UN peace operations in the context of changing conflict dynamics and introduces some of the core tensions that will be discussed in this book.2 It gives an overview of some of most pressing challenges facing the UN, questioning the assumptions surrounding “new threats” of violent extremism. It discusses the internal and...