1.1 Consciousness and Mind: Actualism

Actualism , if it is as much a workplace as a final theory of consciousness and mind, is indubitably also a long way from two main fairy tales still told or remembered.

One fairy tale is that consciousness is just physical—physical stuff or anyway a physical fact. A little more clearly, if not much, consciousness is objectively or scientifically physical. Is that more declaration or even declamation than explanation?

Anyway, it’s said to be material stuff in your head, soggy grey matter as the philosopher Colin McGinn contemplated. Only neural networks , however wonderfully related within and between themselves or to other things. Somehow not different in kind from the stuff or kind of thing, the nature, of the chair under you, or that growing aspidistra plant in the pot over there, or the London bus that got you here.

The second fairy tale is that consciousness is ghostly stuff, as in the old, old Greek philosophical theory of mind-brain dualism — Plato and all that. To use the term “mind-brain dualism ” that way, incidentally, is to go on misusing it—for there being two things with one of them not physical at all and somewhere somehow floating above or around the other.

Or, to forget the ancient Greeks, and come right up to date with this dualism , consciousness is the entirely similar ghostly stuff, said to be “an abstract sort of thing,” in the abstract functionalism of very much twenty-first-century cognitive science, in what can also have the name of being computerism about consciousness.

It’s not good enough that abstract functionalism like the ancient dualism makes consciousness different from everything else, which it does and which any decent theory absolutely has to. It doesn’t help, either, by the way, that abstract functionalism is tied to and owes a lot to the more than uncertain proposition of what is called multiple or variable realizability or realization . That is, to the effect that exactly and precisely the same conscious thought or hope or whatever can go with different brain states. That’s why it’s not identical with any one of them. It’s a good step towards making the floating thought or hope unreal, of course. But we don’t have to go into that.

Abstract functionalism also seems to have among its various shortcomings another one, close enough in my mind to making it nonsensical. The somehow non-physical consciousness itself—however it is somehow tied to what is underneath it or what it’s said to be supervenient on—is itself what philosophers call epiphenomenal . That is to say that unlike what somehow just goes with it, it itself doesn’t cause anything. It never has any ordinary physical effects at all. Yours wasn’t in any way causal, and wasn’t in that way explanatory, with respect to where you are right now, which, you may willingly agree, in good American English, is nuts.

Maybe we do not have to wait for an Einstein of consciousness in order to try to do better than the two fairy tales. And we do not have to join a lot of pessimists in our setting out to solve the problem of consciousness right now. Is it really all that hard, by the way? The hardest problem of all?

Some say so. Maybe if they’re not fully acquainted with other problems in philosophy? Is it as hard as the problem of truth, of what the truth of a proposition is or comes to—maybe the roles in it of what is called correspondence to fact and coherence with other propositions? Is consciousness as hard as right and wrong? As hard as justifying inductive reasoning from past to future? As hard as the nature of time—say the relation of the temporal properties of past, present, and future to the temporal relations of earlier than, simultaneous with, and after?

Anyway, with consciousness , there is something we can start with. This is not just a good idea, which some philosophers get one morning. Quite a few have got one about consciousness.

We can start with a rich database on consciousness in the primary ordinary sense, the main sense in a good dictionary. We can start with this admittedly figurative or metaphorical database, derivable from the language of philosophers, scientists, and others, including you: about 40 items. Owed to their holds on their own consciousnesses, and I trust to yours. Owed to remembering what it was to think something a moment ago, and so on. No stuff there about introspection, inner peering, which led to a lot of dubious psychology in the nineteenth century.

The database includes our taking being conscious in this sense as being the having of something, if not in the literal way you have ankles or money. It includes being conscious as something’s being right there, its being open, its being transparent in the sense of being clear straight-off, its not being deduced, inferred, constructed, or posited from something else. Also its being given, its somehow existing, its being what issues in a lot of philosophical talk of contents or objects. The database includes something’s being present, its being presented, its being to something, its being what McGinn speaks of as vividly naked, and so on.

The database, I say, of which I didn’t make any of it up, does what none of five leading ideas of consciousness do—even if their owners contribute to the database. They are the five ideas about what are called qualia, something it’s like to be a bat, subjectivity , intentionality or aboutness , and phenomenality , whatever it is. The database, that is, adequately initially identifies the subject of primary ordinary consciousness—makes sure that people around here seeming to be disagreeing about consciousness are really answering the same question, not talking past one another. There’s a lot of that in both the past and present of philosophy and science about consciousness . It has a lot to do with disagreement and pessimism about consciousness .

The database, we can say, lets us sum up primary ordinary consciousness or anyway label it satisfactorily as being something’s being actual. As its being actual consciousness .

This consciousness, by the way, is not all of the mental or the mind. It is not that greater stream than the one in William James’s still-cited talk of a stream of consciousness , not the greater one that includes more than consciousness in our sense or any ordinary sense. The mental or the mind includes in it, say, standing or ongoing dispositions or capabilities that enable me right now to do what is different from them, think for a moment of my age or have the feeling that time is passing. And the mental or the mind includes an awful lot more in neuroscience and such related inquiries as linguistics.

The figurative or metaphorical database, with some significant help, including contemplation of various shortcomings of various existing theories of consciousness , and thus the assembling of a specific set of criteria for a good theory, sure leads somewhere—as in many different cases in the history of science itself, including hard science. The figurative database leads to an entirely literal theory, an account of the nature of something, saying what it is, what it comes to, or comes down to: the theory that is Actualism .

The whole theory, as you might expect, given the database, will consist in due course in very literal answers as to (1) what is actual and (2) what its being actual is.

More particularly, the theory in its first section is of what is actual in each of the three different sides of consciousness —perceptual , cognitive , and affective , which roughly means consciousness in seeing etc., consciousness that is thinking, and consciousness that is wanting or feeling or that latter two of those together. Actualism is therefore very unusual, as good as unique, in the philosophy of consciousness in general, complete theories of all of consciousness taken together. It is different in respecting the differences of those three sides, which you may and definitely should find reassuring. Seeing etc. really isn’t like believing—or wanting etc.

The second answer in Actualism , as I say, is of course to what being actual is in the three cases, the three sides of consciousness , what the data comes to in that respect. Not all the same in all cases.

Of course, Actualism is a dualism in the sense that any sane theory of anything is. It makes a difference between consciousness and the rest of what there is. As you will be hearing, that isn’t to say it puts consciousness above anything else, whatever facts there may be that call for or tempt us to such talk.

The database itself, at least most of the pieces of data, seems to have something to do with something’s being physical —maybe or maybe not in the standard sense in science and philosophy, which is to say objectively or scientifically physical .

So too does physicality come up somehow with virtually all theories of consciousness in history. Starting with the denial of physicality in ancient dualism and continuing through a ruck of theories, including materialisms and naturalisms , say Dan Dennett’s , that are to the effect instead that consciousness is somehow objectively or scientifically physical. Presumably, all the theoreticians weren’t ninnies in that preoccupation.

Why not spend some real time getting really straight what being objectively physical is? Why not act with respect to the situation implied quite a while ago by the admirable paper by Tim Crane and Hugh Mellor , “There Is No Question of Physicalism”? It was so titled out of the conviction that no adequate conception of the physical was available, certainly none to be got by exclusive reliance on science.

Could it be that a second source of disagreement and pessimism and worse about the subject of consciousness in philosophy and science, a source in addition to no adequate initial clarification of a subject matter, has been no concentration on the separate question or questions of the physical?

Why not, without following any philosopher’s or scientist’s leap or flight to a generalization, just ask what characteristics the physical world has? Proceed pedestrianly, walk over the ground, work through a subject? Put together a checklist? Didn’t Einstein plod in order eventually to do some leaping, by the way?

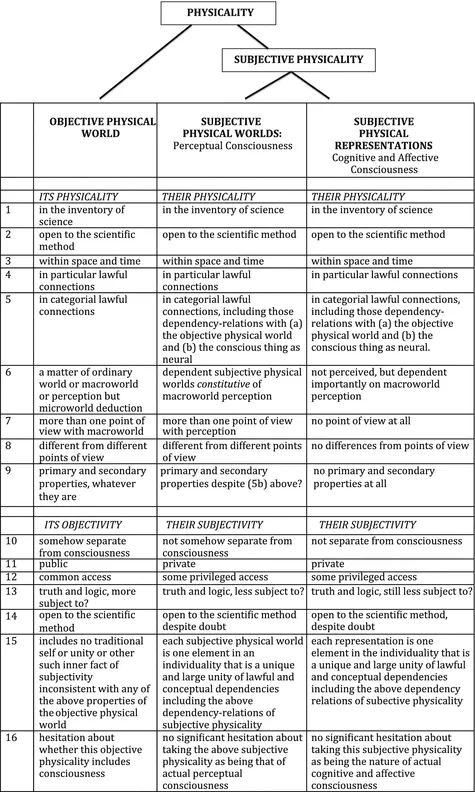

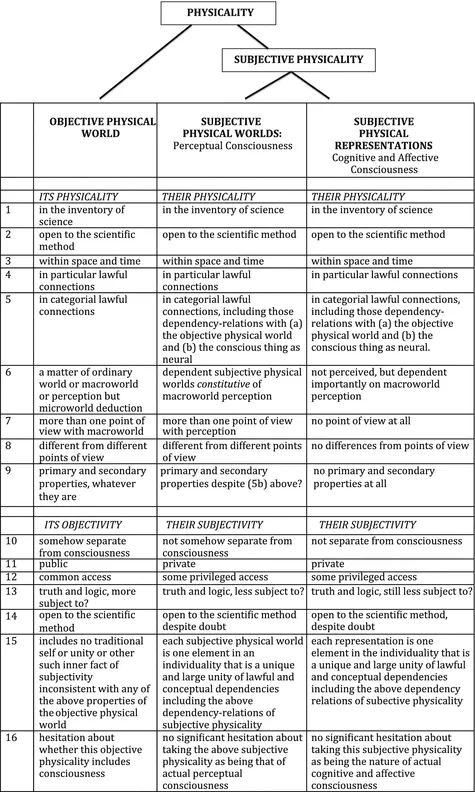

Anyway, here is a comparative table, a summary table, a table of physicalities in general. You can more or less satisfy yourself, I say, that this objective or scientific physicality has 16 characteristics. They are the ones in the left-hand column under the heading “

Objective Physical World ” in the table. An enlarged version to which we will come of this table of physicalities in general, incidentally, will include an additional column—this having been prompted if not suggested by Noam Chomsky’s chapter in this book (Table

1.1).

Table 1.1 Table of physicalities in general

I’d better say that putting the whole table in here is in a way putting the cart before the horse or letting the whole cat out of the bag. The table as a whole from the top heading down has all of it been a kind of summary of the Actualism theory of consciousness as a whole—to which we’re on the way. But so what? This isn’t a detective story or murder mystery. Our use of the table right now is just for its column summing up of what objective or scientific physicality comes to.

Can that understanding of objective physicality somehow lead us to an answer or rather answers to what ordinary consciousness in its three sides comes to? Maybe different answers with perceptual consciousness as against cognitive and affective consciousness , and somewhat different answers with the last two?

But think now about the database that preceded the table and that first question of what is actual with a part or side of consciousness, perceptual consciousness in particular. What is actual right now with your own perceptual consciousness ? I give you the answer free. You’d give it to me if you were asked. It’s the place you’re in, probably a room. A room out there. No other answer is possible. No other kind of answer.

And what is it for a room to be actual? I suppose the res...