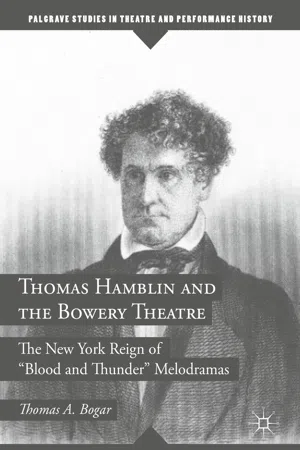

Behind this face (Fig.

1.1) lived two men.

One was a talented Shakespearean actor, a savvy, ambitious theatre manager who persevered against daunting odds. The other was an arrogant sensualist who handily captured the hearts of married women and starry-eyed ingénues, despite an unceasing barrage of public outrage . One day he performed Hamlet to critical acclaim, the next he

haunted the brothels of New York, selecting the teenaged daughters of prostitutes to become favored

protégées . Under his tutelage some of them became celebrated actresses; three died in their early twenties under questionable circumstances.

Few figures in American theatre were as polarizing. Everything he did was extolled or excoriated. To his admirers (and there were many), he was a “noble Roman” who commanded the stage, a hero of the city’s burgeoning working class, a philanthropist willing to help those in need. To his detractors (and there were more), he was an utterly unprincipled libertine, a narcissist who brooked no opposition, a ruthless Machiavellian who destroyed the careers and lives of anyone who stood in his way.

He was Thomas Souness Hamblin, granted by nature with tremendous advantages. Well over six feet tall —at a time when the average male stood at five feet eight inches—he maintained a commanding demeanor. Atop his imposing head a profusion of dark curly hair spilled over a broad forehead, with piercing, dark hazel eyes set in a ruggedly handsome face. A large Roman nose overshadowed a stern, narrow mouth above a square, fleshy, cleft chin. “He was by all odds the handsomest Hamlet I ever saw,” observed one contemporary. Recalled another, “Tom Hamblin! Ah! He was THE looker! [Edwin] Forrest as Coriolanus was great in the region of the calves, but Tom Hamblin was great all over.”1

But nature had shortchanged him with a pair of unshapely tree-trunk legs and an incongruously high-pitched and asthmatic voice. And he lacked refinement, resembling “a country wagoner,” as one observer opined, covered up with an affected theatrical dignity. He wore clothes to great advantage, especially costumes of classical tragedy, and appeared at all times to be posing for a formal portrait. Some saw him as a grand piece of “animated machinery” or a “speaking statue.”2

Hamblin carried himself with supreme confidence , leading with his expansive chest and muscular upper arms. His stride was regal, as if crossing an imaginary stage when a real one was unavailable. Said one reviewer, “he could not ask ‘How do you do?’ nor even blow his nose, without a flourish of trumpets.” “He believed in himself,” recalled a fellow manager , “with an abiding faith that were it not for him the legitimate drama would go to the bow-wows.” Overbearing and imperious, he suffered no fools. “Woe betide the poor dog who dared to bark” against him, recalled one of his actors. If anyone persisted, “the managerial monarch threw back his leonine head, drew himself up to his full height, and glared down at the applicant with such effect that, awed and frightened, [he] oozed out as it were from the lordly presence and troubled him no more.”3

Never a star of the first magnitude like Forrest or Junius Brutus Booth, he was a dogged, workmanlike performer rather than an inspired one, falling short of genius, that gold standard of the Romantic Age. Employing facial expressions which were not particularly flexible or communicative, along with wooden gestures, he personified the outdated “ [John Philip] Kemble School” of acting, not the fiery style of Edmund Kean and Booth , nor the “heroic,” declamatory style of Forrest. When critic William Winter at the close of the nineteenth century enumerated the luminaries of two centuries of Shakespearean acting on the American stage, he omitted Hamblin entirely.

When a scene called for majesty or dignity, Hamblin was fine, but was somewhat at sea when tenderness or love was required. Noble Romans were his forte, and he drew applause by striking a noble pose and (except when asthma assailed him) delivering a grandiloquent, inspirational speech: “To see him dressed for Brutus , Coriolanus , or Virginius was study for a painter.” These were his best roles, along with Tell , Macbeth , Othello , Faulconbridge, and Rolla. Curiously, he often chose the brooding, philosophical Hamlet to open his engagements; the excessively ambitious Macbeth would have been more apt.4

Still, he remained a popular success, one of the best-known actors in America during his lifetime, with John R. “Jack” Scott close behind. No figure in nineteenth-century American theatre was more truly sui generis. Those who appreciated his performances the most were neither aesthetes nor aristocrats. He was “a sure card with the East-side patrons [who] could bellow with the best, ‘tear a passion to tatters, to very rags,’ ‘split the ears of the groundlings,’ and thus made himself a hero with men and boys who doted on caricature.”5

As a manager, Hamblin was fiercely, inventively competitive. Defying the prevailing norm of aristocratic theatregoing as exemplified by the nearby Park Theatre , he wooed and won the b’hoys and g’hals of his Bowery Theatre pit and gallery, and his vision and instincts were keenly attuned to their expectations. His three tenures at the helm of the Bowery—a combined seventeen years—showcased a kaleidoscope of sensational, often gory, “blood and thunder” melodramas, leading it to become known as the “Bowery Slaughterhouse.” He was arguably more responsible for the popularity of spectacular melodrama in America, especially among the working class, than any other theatrical figure. As Bruce McConachie has noted, Hamblin “pioneered the innovations that established working-class theatre as a separate form of entertainment.”6

This was largely achieved by the exertion of Hamblin’s monumental ambition and commensurate pursuit of adulation, which were unsurpassed in his era. His ancillary need for respectability, however, remained unfulfilled. To meet the needs of his new working-class audience, he dished up plenty of pulchritude, lavish apocalyptic spectacles, patriotic homages to historical events, classical tragedies, farcical afterpieces (but few comedies), and—anticipating vaudeville by half a century—novelty acts gyrating from minstrelsy to elephants to equestrians to dogs. Eschewing the star system except for heroic figures like Forrest and Booth who appealed to his targeted audience, Hamblin developed a native American stock company to carry productions in which the ensemble, the special effects, and the blatant themes of egalitarianism and virtue triumphant compensated for the lack of a major star. His actors were in general not the most talented, but his selection of popular scripts and their spectacular staging ensured that his theatre generally remained full. And, significantly, he readily adapted to his adopted nation. Despite living the first thirty-eight years of his life as a native Englishman, he flourished as a nativist American manager.

Each time that he struck success, often with a thrilling adaptation of a recent popular novel, he launched it into a groundbreaking long run. A few extraordinary successes he milked for years. No one, with the exception of the incomparable Phineas T. Barnum , kept himself and his theatre so consistently in the public eye. In this, Hamblin served as a prototype for such impresarios as John T. Ford, Augustin Daly, David Belasco , and (especially) Florenz Ziegfeld.

But Hamblin’s hallmark, which stamps him indelibly as worthy of historiographical consideration, was a resilience which carried him past any obstacle, any setback. The overriding arc of his life was his determined battling back after repeated severe—almost biblical—trials. Considering the vicissitudes of theatrical management in the 1830s and 1840s, it is a wonder that he kept his Bowery Theatre afloat through exceptionally parlous times, especially in the wake of riots and the Panic of 1837 . Season after season, he frantically juggled attractions and—despite a proclaimed aversion to the “star system”—enough stars to keep the Bowery going.

Manager Francis Wemyss , who knew Hamblin well, watched him “struggling undismayed against reverses which would forever have prostrated common men.” “Surely ninety-nine men out of a hundred would have caved in and gone through under half the misfortunes which have assailed him,” observed William T. Porter, editor of the New York Spirit of the Times. A “man of untiring industry,” Hamblin remained utterly unflappable, upheld throughout his unceasing financial and marital travails by loyal male friends. Numerous accounts tell of his animated camaraderie, throwing back many a drink and swapping many an anecdote (often ribald). True, he also generated “some implacable enemies; but the public almost universally followed his footsteps and supported him liberally.”7

Hamblin’s contempora...