But, to come to a conclusion, though I cannot think that Coleridge ever worked with his mind clear, or was, indeed, capable of the necessary concentration and steadiness of thought by which alone philosophical achievements are possible; though I hold, again, that if he had succeeded he would have found that he was not so much refuting his opponents as supplying a necessary complement to their teaching, I can still believe that he saw more clearly than any of his contemporaries what were the vital issues; that in his detached and desultory and inconsistent fashion he was stirring the thoughts which were to occupy his successors; and that a detailed examination would show in how many directions a certain Coleridgian [sic] leaven is working in later fermentations . 1

Leslie Stephen (1879)

There are, I think, distinct traces of a Coleridgean legend which has only slowly died out. The actual truth I believe to be that Coleridge’s position from 1818 or 1820 until his death, though one of the greatest eminence, was in no sense one of the highest, or even of any considerable influence […]. A few mystics of the type of Maurice, a few eager seekers after truth like Sterling , may have gathered, or fancied they gathered, distinct dogmatic instruction from the Highgate oracle; and, no doubt, to the extent of his influence over the former of these disciples, we may justly credit Coleridge’s discourses with having exercised a real if only transitory directive effect upon nineteenth century thought. But the terms in which his influence is sometimes spoken of appear, as far as one can judge of the matter at this distance of time, to be greatly exaggerated. 2

H. D. Traill (1884)

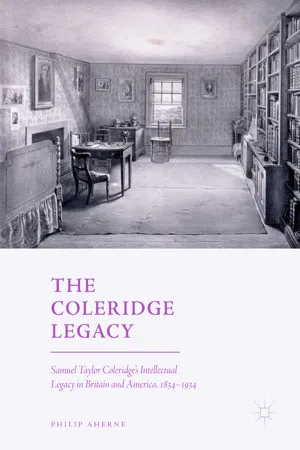

The engraving of George Scharf’s (1788–1896) forgotten watercolour of Coleridge ’s chamber at Highgate reveals many of the qualities of Coleridge’s intellectual legacy: all the details point to his presence, and yet he is absent. 3 Numerous specific aspects of the picture invite the observer to imagine how Coleridge used the room: the faint lettering that runs across the spines of his studiously read book collection; the wooden floorboards that crease the slightly ragged carpet where he would have paced; the papers that are strewn across the desk, suggestive of the numerous works-in-progress that he left unfinished; the view from the window that many would have seen when they visited him. Paradoxically, the picture manages to provide a clear depiction of the ageing intellectual despite—or because of—his exclusion. It also allows modern readers of Coleridge’s works to see the room where numerous major ideas that helped to shape the intellectual climate in Britain and America in the nineteenth century originated. For the ghosts of Coleridge’s numerous visitors—from John Sterling (1806–1844) to Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882)—also seem to linger in the room, much like Coleridge’s voice. It was here that groups of young, intelligent men (and women—plenty attended, but few are discussed here for reasons that will become apparent) would gather around Coleridge and listen to him talk . This weekly ritual was the foundation stone of his then popular reputation as the ‘Sage of Highgate ’. The room existed without Coleridge, and yet it was still distinctly ‘Coleridgean ’. Coleridge’s legacy is also characterized by this elusive quality: ideas persisted without him there to champion them; despite the many distortions and developments they underwent, they still retained their ‘Coleridgean’ essence.

Much

like Scharf’s picture, there is plenty of explicit contemporary evidence for the existence and importance of Coleridge’s influence.

John Stuart Mill (1806–1873)

coined the term ‘Coleridgian’, using it as an adjective and, perhaps more importantly, as a noun, specifically to describe a follower or devotee of the man and his works.

4 Effectively announcing himself as an example of this new type of disciple, he opened his 1840 essay by confidently asserting that ‘the

name of Coleridge is one of the few English names of our own time which are likely to be oftener pronounced, and to become symbolical of more important things, in proportion as the inward workings of the age manifest themselves more and more in outward facts’ because ‘no one has contributed more to shape the opinions of those among its younger men, who can be said to have opinions at all’.

5 Matthew Arnold also

celebrated Coleridge’s intellectual tenacity: ‘But that

which of Coleridge will stand is this: the stimulus […] of his continual instinctive effort, crowned often with rich success, to get at and to lay bare the real truth of his matter in hand, whether that matter were literary, or philosophical, or political, or religious; and this in a country where at that moment such an effort was almost unknown’.

6 Additionally, the American

Charles Eliot Norton (1827–1908) concluded his 1855

memoir of Coleridge’s life by graciously asserting:

His influence on thought has been transmitted through the lives and works of many men, who, though not to be classed as his disciples, yet received from him intellectual stimulus and fertilization […] There is scarcely one of the English thinkers of the present day who does not owe much, directly or indirectly, to the teachings of Coleridge. 7

The nature of Coleridge’s influence to be as discreet as it was powerful, and for it to essentially animate thought, was also recognized by the now neglected British philosopher Shadworth Hodgson (1832–1912), who claimed in 1878 that ‘the world too has far more to learn from Coleridge than it yet dreams of, not by way of system or theory, but by way of vivifying impulse’. 8 The sheer confidence of these statements constitute a challenge to our current understanding of Coleridge’s influence: his admirers appreciated his intellectual achievement and were certain that his ideas would have a profound and lasting effect upon a whole generation of thinkers, and yet our knowledge of the practical nature and actual outcomes of this process is, by comparison, extremely limited.

It is the difficult and delicate task of this book to excavate Coleridge’s intellectual status by situating him in the landscape of nineteenth-century transatlantic thought in order to rectify this critical deficit. However, the nature of the development of his intellectual legacy is, in fact, what makes it such a difficult topic to analyse: it is at once both secure and elusive, direct and indirect. The two epigraphs illustrate the divergent approaches that the area has long inspired; they encapsulate the central division at the very heart of the subject, which precludes analysis of it: the issue of Coleridge’s proximity to his own (perhaps supposed) influence. It has been recently observed that ‘critical writing about Coleridge is labyrinthine , but not unlike Coleridge’s own prose, no serious reader of Coleridge disdains a labyrinth’. 9 To accommodate this metaphor: writing about Coleridge’s influence is like trying to navigate a collection of labyrinths that have, for some inexplicable reason, all fallen in on each other whilst simultaneously retaining their original structure, not unlike trying to follow Coleridge’s prose and the scholarly footnotes at the same time—as any serious reader of Coleridge knows, they frequently lead in dramatically different directions. The metaphor is durable: an anonymous contemporary reviewer described the difficulty of following Coleridge’s philosophy through his prose as akin to navigating an ‘endless labyrinth’. 10 Similarly, Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) celebrated Coleridge’s diffuse suggestiveness by commenting that ‘as we enter his radius he seems not a man, but a swarm, a cloud, a buzz of words, darting this way and that, clustering, quivering and hanging suspended’, and consequently ‘we become dazed in the labyrinth of what we call Coleridge to have a clear picture before us’. 11 Alternatively, some argued that there was always a way out: a member of his contemporary audience who heard his monologue acknowledged that ‘while he led you through a labyrinth, too long, perhaps, and intricate for you to thread of yourself, you have supposed that you held all the while the silken clue in your own hand’. 12

Coleridge’s variety quickly becomes an immediate problem when trying to comprehend his intellectual output, and thereby trace the ‘silken clues’. He was engaged in a vast array of intellectual disciplines , of which just some include philosophy, theology, poetry, criticism, politics and sociology. He also operated in a number of modes: he was a journalist, a playwright, a poet, a lecturer , a preacher, a conversationalist, an essayist and a critic. His engagement in these fields is complicated. He was deeply invested in intellectual history; therefore, his thoughts on philosophy (for example) need to be understood in the context of the complex and prolonged debates that preceded him and to which he was referring directly. The nature of those thoughts is also a vexing issue. Many of Coleridge’s extant prose writings were in a state of flux: his political journal The Friend , for example, was redrafted numerous times, each version different from that which preceded it; a number of his major positions were evolved in his private notebooks and in his marginalia (both of which have been subjected to rigorous scholarly editing fairly recently); he would often give his lectures ad lib or from these notes—be...