![]()

Chapter 1

Disappearances/Spaces of Violence: Kuitca’s Painting and Salcedo’s Sculpture

A comparison between Colombian artist Doris Salcedo (b.1958) and Argentinian Guillermo Kuitca (b.1961) seems counterintuitive. Their differences in medium, aesthetic practice and political conviction about the role of art in society are simply too big. While both belong to the same generation of Latin American artists and began their careers in the early to mid-1980s, they work in fundamentally different media: Salcedo in sculpture and installation after training as a painter; Kuitca in a decisive return to painting after the Argentinian enchantment with Duchampism in the post-1960s. Their home countries share a history of state violence, but they have responded to it in quite different ways. Kuitca’s work emerged at a time of extreme crisis in the year of the Malvinas (Falklands) War (1982), when the Argentinian military dictatorship was significantly weakened and its end could already be imagined, whereas the experience shaping Salcedo’s early work was a highpoint of Colombian violencia, the attack of guerrilla forces on Bogotá’s Palace of Justice and the ensuing massacre. Only Salcedo, however, became the artist fully and empathically engaged in memory art, while Kuitca’s work relates to the Argentinian Dirty War in more indirect ways, which operate under the surface of his painterly project, the painting of space as subject to disintegration. And yet it is precisely the juxtaposition with Salcedo’s memory sculptures that permits us to shed light on Kuitca’s hidden political beginnings, and on the ways in which the experiences of the Jewish diaspora and of the military dictatorship actually shaped his life-long obsession with securing spaces of refuge and stability in his painting.1 Clearly, their different aesthetic handling of the political is grounded in the specific situations they were responding to. Kuitca reacted against the prevalence of explicitly political art in the Argentinian transition from dictatorship to democracy in the 1980s, whereas Salcedo reacted to the absence of public mourning regarding the ever mounting toll of Columbia’s decades-long civil war. Salcedo’s work, highly mediated through her meticulous work on materials, is always openly political in its references to the violence that has convulsed Colombia in waves ever since the late 1940s. The public invisibility of acts of violence itself is the mark of her aesthetic practice, which has violence as its theme. The call to collective and individual grieving for the victims of the civil war is embedded in aesthetic forms that require the viewer’s sustained attention and extended contemplation of the work.

Guillermo Kuitca, by contrast, has mostly shied away from articulating any specific political message, except for one very early work of 1980 entitled 1–30000. On a large canvas he inscribed numbers from 1 to 30,000 in tiny, densely packed handwriting, which if seen from a distance appears as a grey greenish monochromatic color field – the only direct reference in his work to the victims of Argentinian state terror. For many years thereafter, he has resisted political readings of his work. And yet, there is that series of paintings from 1982, Nadie olvida nada (Nobody Forgets Nothing), an incisive reflection on the effects of state terror, which I see as ground zero of his later trajectory. It was created at a time when he was enthusiastically caught up with the dance theater of Pina Bausch, which made him think that everything could be done in the theater and nothing in painting. With painting in an allegedly terminal crisis, this was his way to deal with the Entgrenzung of painting to other media, in his case the theater. The Nadie olvida nada series was actually shown together with Kuitca’s staged readings of a collage of texts by authors such as Juan Goytisolo and Elias Canetti. While that performance is not well documented, Kuitca recently put it this way: ‘The painting series was like an exercise in constraint while the performance was a ground to upload all sorts of things with no other filter than the urgency.’2 The urgency referred to the political situation of the Malvinas War and the anticipated fall of the military regime. It was the extreme pressure of the times, both political and aesthetic, that created the constellation of these early paintings and the theater, which in turn grounded the rebirth of painting in his career. The theater remained as a theme of painting in his work, not as an aesthetic practice of performance. It was like a retraction of the abandonment of painting that had tempted him after experiencing the power of Pina Bausch’s choreography.

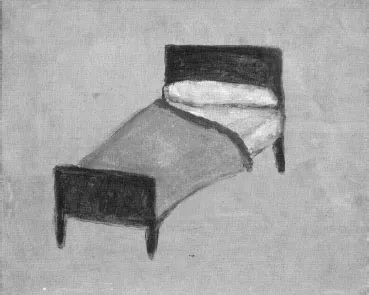

Nadie olvida nada is a series of small minimalist paintings in acrylic on wooden boards or simple cardboard, most of them featuring a simply drawn empty bed with small, barely sketched human figures at some distance from the bed and seen only from behind. Bed and figures appear to be floating in empty space, some with intensely colored backgrounds in reds, yellows or browns. Perspective is limited to the shape and position of the bed. Otherwise, there is spatial limbo. The figures are marked as predominantly female. In one of the images, a woman is led away by two men in the painting’s center, with other figures dispersed and forlorn in space and part of a bed emerging from a white-grey blotch of paint near the left margin (fig.1). In another, eight women all seen from behind appear lined up horizontally as if to be executed. They stand next to each other in the middle ground of the painting, arms and hands not visible from behind, with the uniformly yellow top garment between their black skirts and their black hair suggesting targets for an invisible firing squad. The series exudes a sense of alienation, placelessness and immutability. The small scale of the works, their somewhat unfinished look and the sketchy outlines of the figures betray a kind of hesitation on the part of the artist to engage with the topic of disappearances too directly. Kuitca approvingly cites a critic’s observation that these paintings looked as if they had come about by the paintbrush being held still and the canvas itself moving to produce the images.3 I would read it as an écriture automatique (automatic writing), executed under extreme psychic pressure of a historical moment. And then there is the single bed against a yellow background, painted on cardboard, with its cover neatly at an angle leaving an opening for an absent person to slip in (fig.2). As these paintings subtly but unmistakably comment on each other, the spectator must ask: What else is the empty bed than a bed emptied after its occupant has been taken away and disappeared? After the state has violently intruded on that most private and intimate space? The multiple paintings of the series suggest traumatic repetition precisely by their lack of spatial or temporal grounding.

Fig.1 Guillermo Kuitca, Nadie olvida nada, 1982

Acrylic on wood, 122 × 154 cm (48 × 60 ⅝ in)

Private Collection, Buenos Aires

With its reference to forgetting and the visual presence of empty beds and chairs, Nadie olvida nada assumes its unmistakable political readability, especially if we juxtapose it to Salcedo’s sculptural treatment of domestic furniture in works such as Casa Viuda (Widowed House, 1992–5) or Unland (1995–8). My rather minimalist point de départ then is the mere presence of chairs, beds and doors in their early work, which, in both artists, is related to the violation of private intimate space by the state’s security forces or right-wing death squads. But even here the differences are salient. There is something tentative and delicate about Kuitca’s Nadie olvida nada series of 1982, whereas Salcedo’s mutilated and concrete-filled domestic furniture sculptures from the 1990s are barren and even brutalist in their physical presence. Violence on humans is differently conjured up without ever being shown by either artist.

Fig.2 Guillermo Kuitca, Nadie olvida nada, 1982

Acrylic on canvas-covered hardboard, 24 × 30 cm (9 ½ × 11 ¾ in)

Collection of the artist

Perceived as the site of birth, sexuality and death, the bed is key to any notion of privacy, intimacy and family life. In a psychoanalytic reading, Nadie olvida nada, with its double negative, diagrams a process of memory and repression central to the Freudian understanding of traumatic memory. The ‘absolute absorption’4 Kuitca mentions as its origin is clearly significant. The series represents a veiled articulation of collective trauma and his own sense of vulnerability during his teenage years. The intensity of the historical moment, when the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo were already marching, requesting information about their disappeared children, may have had something to do with the ‘absolute concentration and the absolute commitment’ that saw the series of paintings come to light.5

We need to ask further. Who might be the nobody of the title who forgets nothing? What is the nothing? What does the forgetting refer to? Clearly, taken together, the images of this series are marked by a resistance to forgetting the state terror perpetrated by the military dictatorship and its clandestine killing squads from 1976 to 1983. Instead of calling for commemoration in the spirit of the 1984 National Commission’s report on the crimes of the regime entitled ‘Nunca más’ (‘Never again’), Kuitca’s title with its puzzling double negative poses a riddle that requires unpacking.

We know how dictatorship threatens private space, how people are pulled out of bed and arrested in their homes at night when they are most vulnerable. Salcedo’s sculptures are marked by such violence, visible in their gouges and mutilations, but Kuitca’s series gives no such clues. The ‘nada’ of the title captures the absence, the void into which the Argentinian desaparecidos have been thrust. Implied in the title by way of a third negation is the idea that everybody remembers everything. But Kuitca’s phrasing recognizes the impossibility of such a remembering. After all, what happened to the desaparecidos in captivity cannot be remembered as long as it remains undocumented. This lack of knowledge is captured in the title with the word ‘nada’: if there is nothing specific to remember beyond the mere fact of disappearance, there will be nothing to forget. There is added significance to the fact that all figures in the series are drawn schematically from behind. The absence of faces points to the voiding of individuality by state terror. And ‘nadie’ is not everyone remembering or forgetting, anyway. It is a figure of the void. The bodies represented in these paintings are the nobodies, barely visible in their contours, sometimes drawn in white, sometimes with simple lines in black, but always without individualized features. This is figuration at a degree zero, close enough to the total absence of figuration in the work of Salcedo. Trauma, as Freud knew and Kuitca shows, does not lend itself well to narration; nor can it be captured visually in figuration.

Ultimately the nobody of the title points to Kuitca himself, who is known for shunning self-expression. It is as if he hides behind the word ‘nadie’, just as Homer’s Odysseus did when he faced the deadly threat of the one-eyed giant Polyphemus, giving his name as udeis, i.e. nobody, the better to escape from mythic fate. Analogously, Kuitca deploys the self-denial of nadie as a means of aesthetic and political self-preservation. By linguistically and pictorially wiping out subjective experience as well as empirical representation of the state terror, the objective space of memory is preserved all the better. This denial of self and subjectivity, present in a different form in Salcedo’s work, stands in a long tradition from Franz Kafka to Samuel Beckett. Kuitca makes self-conscious use of this major trope of modernism, thus subtly giving shape to a very specific historical moment in Argentina – the anticipated end of the military dictatorship and its future in memory.

When asked in a later retrospective interview about the emergence of the bed as a leitmotiv in 1982, Kuitca said ‘the bed became a refuge, a territory’. And then he went on to erase any overt political reading of the bed by reading it simply in terms of a space:

The bed now is a stage. On the surface of the bed you can trace a line. The bed becomes an apartment. The bed is land. The bed is a city. Ultimately the bed is theatre. At first the bed features in a big room, a large space with small objects. The bed becomes a way of setting the space.6

This indeed does describe the evolution of Kuitca’s career as a painter from the 1982 beds via the El mar dulce (The Sweet Sea) series and the ‘houseplans’ (home as another place of refuge) to the disorienting maps, painted in acrylic onto mattresses, thus combining intimate place and extended abstract space (fig.3). The dialectic of the bed as a site of extreme vulnerability and as refuge is central to all of Kuitca’s work. It sets the space he has explored as a painter.

The bed, the houseplan, the home as refuge point to another dimension of Kuitca’s early work, that of the Jewish diaspora in exile, which merges with the precariousness of life under the dictatorship. Key here are several painterly references to the famous scene in Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin (1925) where an abandoned baby carriage rolls down the steps in the midst of the mayhem of the government’s violent suppression of a strike. The filmed scene took place in Odessa, home of Kuitca’s grandparents before they fled Russian pogroms and emigrated to Argentina.

Whether bed or baby carriage, it is always much more than just a setting of space. Given the continuing use of the bed as surface, later transformed into houseplan, or maps of cities and fictional countries, its emergence as a leitmotif highlights its role as refuge, and yet a potentially precarious and endangered space constitutive of Kuitca’s overall painterly project. The bed became the basic model for all of his diagrams, which capture the visual world beyond figuration and beyond abstraction. Kuitca always refused to be called an ‘abstractionist’. To him, diagrams are neither abstraction nor successful representation.7 By side-stepping the discourse that pits abstraction against figuration, and visual presence of illusion versus its absence, Kuitca has successfully expanded the boundaries of painting itself. His work has created a new kind of image that remains representational in a non-mimetic mode, cool and yet sensual, geometric but delirious with color, co...