- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

What if scrapping one flawed policy could bring US cities closer to addressing debilitating housing shortages, stunted growth and innovation, persistent racial and economic segregation, and car-dependent development?

It's time for America to move beyond zoning, argues city planner M. Nolan Gray in Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix It. With lively explanations and stories, Gray shows why zoning abolition is a necessary—if not sufficient—condition for building more affordable, vibrant, equitable, and sustainable cities.

The arbitrary lines of zoning maps across the country have come to dictate where Americans may live and work, forcing cities into a pattern of growth that is segregated and sprawling.

The good news is that it doesn't have to be this way. Reform is in the air, with cities and states across the country critically reevaluating zoning. In cities as diverse as Minneapolis, Fayetteville, and Hartford, the key pillars of zoning are under fire, with apartment bans being scrapped, minimum lot sizes dropping, and off-street parking requirements disappearing altogether. Some American cities—including Houston, America's fourth-largest city—already make land-use planning work without zoning.

In Arbitrary Lines, Gray lays the groundwork for this ambitious cause by clearing up common confusions and myths about how American cities regulate growth and examining the major contemporary critiques of zoning. Gray sets out some of the efforts currently underway to reform zoning and charts how land-use regulation might work in the post-zoning American city.

Despite mounting interest, no single book has pulled these threads together for a popular audience. In Arbitrary Lines, Gray fills this gap by showing how zoning has failed to address even our most basic concerns about urban growth over the past century, and how we can think about a new way of planning a more affordable, prosperous, equitable, and sustainable American city.

It's time for America to move beyond zoning, argues city planner M. Nolan Gray in Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix It. With lively explanations and stories, Gray shows why zoning abolition is a necessary—if not sufficient—condition for building more affordable, vibrant, equitable, and sustainable cities.

The arbitrary lines of zoning maps across the country have come to dictate where Americans may live and work, forcing cities into a pattern of growth that is segregated and sprawling.

The good news is that it doesn't have to be this way. Reform is in the air, with cities and states across the country critically reevaluating zoning. In cities as diverse as Minneapolis, Fayetteville, and Hartford, the key pillars of zoning are under fire, with apartment bans being scrapped, minimum lot sizes dropping, and off-street parking requirements disappearing altogether. Some American cities—including Houston, America's fourth-largest city—already make land-use planning work without zoning.

In Arbitrary Lines, Gray lays the groundwork for this ambitious cause by clearing up common confusions and myths about how American cities regulate growth and examining the major contemporary critiques of zoning. Gray sets out some of the efforts currently underway to reform zoning and charts how land-use regulation might work in the post-zoning American city.

Despite mounting interest, no single book has pulled these threads together for a popular audience. In Arbitrary Lines, Gray fills this gap by showing how zoning has failed to address even our most basic concerns about urban growth over the past century, and how we can think about a new way of planning a more affordable, prosperous, equitable, and sustainable American city.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Arbitrary Lines by M. Nolan Gray in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

CHAPTER 1

Where Zoning Comes From

For many Americans, their singular experience with city planning is a little game called SimCity. First released in 1989 and developed by legendary game designer Will Wright, the game invites players to plan their own cities. More of a sandbox than a conventional game with points or levels, each new “round” of SimCity presents players with a virgin field, the power to map out streets and zoning, and the freedom to do whatever they like from there. Poor planning decisions are punished with blinking indicators and unsolicited advice from AI advisors; wise planning decisions are rewarded with happy simulated citizens and a growing city.

Throughout the game, zoning is the essential power in the player’s arsenal, granting them the ability to plop residential subdivisions here or industrial parks there, all while keeping incompatible uses separate. Pursuant to a grand, long-term vision, they can coordinate density to reflect the available infrastructure, keeping the city running like a well-oiled machine. All of these zoning decisions unfold without the pesky intervention of local politics; there are no ornery community boards or NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) litigants in SimCity. The player-as-zoning-tyrant acts alone, beneficently applying their technical expertise to advance the general welfare of their growing city.

As you might expect, SimCity leaves a lot to be desired from a realism perspective: zoning isn’t really about separating incompatible uses or coordinating densities, and local interest groups completely drive the process. Yet it’s telling as a Rorschach test for how we think cities work: without zoning, the thinking goes, cities wouldn’t work. While we today take the comprehensive, top-down control of land uses and densities for granted, the truth is that zoning is quite new. For most of human history, land uses casually intermingled and densities were capped by technological constraints more so than regulatory fiat. Disputes were generally settled among neighbors, and only the most obnoxious uses were banished to discrete districts. Rules on heights and setbacks, where they existed at all, were a function of health and safety considerations.

In the late nineteenth century, technological advances would allow cities to grow up and out like never before. By 1920, America had become a majority-urban nation. It’s in this context of intense change that the seeds of a peculiar institution called zoning began to take root. While the rise of noxious urban industries or mounting infrastructure pressures are often assumed to be the key motivators for adopting zoning, the reality is more complicated. In most cities, bothersome industries and booming infrastructure demands were issues long before the first modern zoning code was adopted in 1916. Better yet, rules and agencies were already addressing these issues in many American cities by the time zoning came online. What did zoning add?

Far from merely sorting out incompatible neighbors or coordinating growth, zoning aspired to rationally restructure and reorganize cities around the needs and preferences of the elites of a particular time and place. Beyond merely managing pollution or rationally allocating densities, zoning was the product of a strange coalition of interests who broadly sought to enrich incumbent property owners, lock existing neighborhoods in amber, institutionalize segregation, and mandate a sprawling vision of growth. Its defining contribution was to enshrine the single-family house as the urban ideal, while casting apartments as mere “parasites” and corner groceries as threats to public welfare. Absurd and unsavory though these positions may read to modern eyes, these peculiar motivations continue to form the basis of zoning to this day.

The first American zoning codes came online in 1916, riding on a wave of elite support spanning from commercial landlords to affluent homeowners. While New York City’s 1916 Zoning Resolution usually gets all the attention, Berkeley, California’s 1916 districting ordinance is more interesting to the extent that it comes closer to what zoning would eventually become. From these codes, each partly a response to a building boom, partly a response to specific groups of unwanted immigrants—Chinese in Berkeley, Eastern European Jews in New York City—zoning would slowly spread before getting a massive boost from the federal government.

Beginning in the early 1920s, then Secretary of Commerce—and future president—Herbert Hoover would draft and aggressively promote model state enabling legislation to allow municipalities to adopt zoning. In 1926, the Supreme Court gave zoning its blessing in Euclid v. Ambler, launching a nationwide boom in zoning adoption. And in the postwar period, through a steady stream of carrots and sticks from the federal government, zoning finally spread to cover nearly every incorporated area of the country alongside the rapid, federally subsidized emergence of suburbia. Most local governments had quietly adopted zoning by the 1970s, at times as a condition for receiving coveted federal funding for transportation infrastructure, housing subsidies, or disaster recovery.

The history of zoning, like the institution itself, is messy—perhaps by design. But if you take nothing else from this chapter, remember this: the comprehensive use segregation and density controls envisioned by zoning are a relatively recent invention. Far from the SimCity fantasy of merely regulating noxious uses or rationalizing growth, zoning’s purpose from the start has been to prop up incumbent property values, slow the growth of cities, segregate the United States based on race and class, and enforce an urban ideal of detached single-family housing. While occasionally characterized as a bottom-up movement, the system we have today was heavily shaped by elite preferences of yesteryear and spread with persistent support from the federal government.

Land Use before Zoning

As normal as the typical American city may seem today, it has about as little in common with historical cities as a pug has with a wolf. These differences are most pronounced when it comes to the way we segregate uses and restrict densities. Take land use. Historically, there was comparatively very little segregation by use within cities, with shops, apartments, workshops, and mansions commonly intermingling.1 There was likewise little distinction between home and work, with many urban residents either working in, or immediately adjacent to, their homes.

The same is true of density. The principal regulator of density was historically technology. A lack of cars or transit meant that most people walked, setting physical limits on the ability of cities to expand outward. In practical terms, this meant cities had to be compact, with even the largest cities constrained to a one-and-a-half-mile radius, such that even an edge-dweller could reach the core by foot within thirty minutes. Before the rise of innovations like steel framing or the elevator, building up was similarly restricted by gravity. Beyond a half dozen or so stories, building taller became uneconomical, as the base would have to expand to bear the full weight of the added stories.

This isn’t to say that there were no formal use or density restrictions before the rise of zoning. For starters, the common law offered certain mechanisms whereby neighbors could seek relief from bothersome uses. If a use came with unwanted negative externalities—such as noise, smells, or pollution—a neighbor could seek an injunction against it as a private nuisance. In many cases, such land-use conflicts were resolved without even going to court, with the mere threat of litigation forcing neighbors to find a mutually agreeable compromise.

For certain uses bound to irritate neighbors—such as brickyards or tanneries—many cities and towns explicitly barred them from city limits or segregated them to the edges of town on the basis that they would be a public nuisance anywhere else. Similar regulations would address building materials and heights on the basis of fire safety, and beginning in the second half of the nineteenth century, many cities would adopt increasingly stricter housing standards to address public health concerns. While highly imperfect, this system largely addressed the challenges posed by urban land uses and densities without requiring regimented land-use controls.

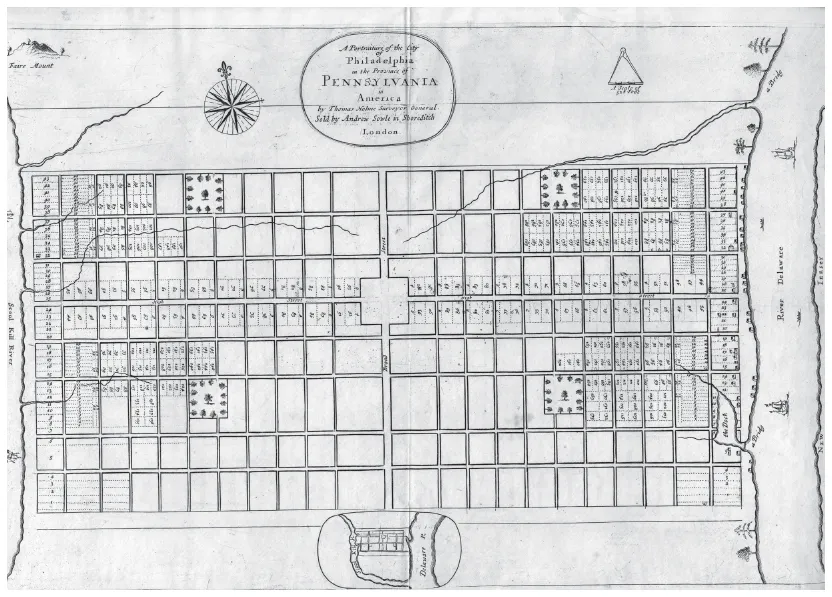

Beyond districting noxious uses, city planning more broadly also preceded the rise of zoning. Nearly every great civilization has imposed some form of city planning, from the street grids of ancient Rome to the caste segregation of Vedic India. In the American context, many major cities, beginning with Thomas Holme’s grid plan for Philadelphia, had adopted master street plans. This effort to plan cities went up a notch in the 1890s, with the City Beautiful movement giving rise to monumental public spaces across the country.2 Similar movements surrounding parks and sewer improvements meant that by the 1910s, robust city planning institutions were already forming in most cities.

Thomas Holme’s 1682 grid plan for Philadelphia. Note the regular interspersed parks and the central plaza. Physical planning of this nature precedes zoning by thousands of years. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College)

What Changed?

By the 1940s, something had changed such that most major US cities had adopted a new and far more comprehensive set of land-use regulations: zoning. The noise and pollution associated with industrialization and the need to coordinate densities with public infrastructure improvements are often offered up in retrospect as the basis for modern zoning. Yet by the 1910s, neither issue was getting worse—indeed, after a century of trial and error, both were almost certainly getting better, with most American cities sporting sophisticated sewer and transit systems. What changed, such that a dramatic rethink of how we plan cities was seen as necessary?

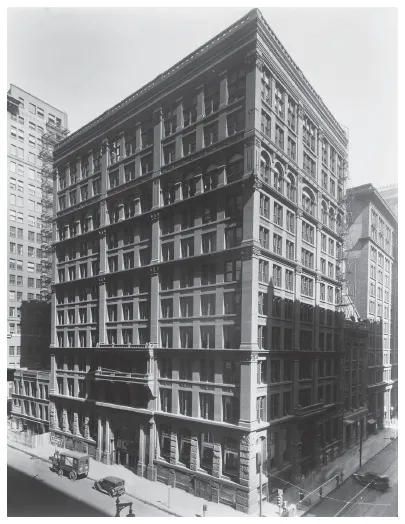

In the late nineteenth century, major technological innovations removed traditional barriers to urban growth: innovations in building technology removed barriers to vertical expansion in the second half of the nineteenth century. With the first steel-frame building going up in Chicago in 1885, the physical constraints associated with load-bearing walls were removed, allowing structures to efficiently rise ten stories and above for the first time. Rapid improvements in elevator technology, such as Elisha Otis’s safety locking mechanism, took the burden out of having an upper-floor office or warehouse. Collectively, these innovations allowed developers to build exponentially more floor area on the same plot of land, allowing densities to follow demand.3

All of this building supported ongoing urban industrialization between 1890 and 1920, leaving cities with a near insatiable appetite for labor. Between the mechanization of agriculture and this surging demand for industrial labor, mass migration from the countryside began, including among African Americans moving from the South as part of the Great Migration.4 Concurrently, millions of immigrants flowed from southern and eastern Europe into northeastern and midwestern US cities, and to a lesser extent from East Asia into West Coast cities. Cities such as Providence, Cleveland, and Los Angeles grew by a startling 50 percent or more between 1890 and 1920. This in turn triggered a boom in apartment construction, as demand for housing ballooned.

The Home Insurance Building in Chicago, completed in 1885, is widely regarded as the first skyscraper for its use of a steel frame. The building was subsequently demolished and replaced with an even taller skyscraper in 1931. (Chicago Architectural Photographing Company, Library of Congress’s National Digital Library Program)

These innovations also gave rise to high-rise offices, supporting the agglomeration of major business districts and assembling the remarkable skylines that many American cities enjoy today. Never before was it easier to locate a firm in a central area, and never was it more important, as industrialization gave rise to a new class of big businesses with substantial office-space demands. While successive cycles of office building boom and bust were good for these commercial tenants, the steady supply of new office and industrial space kept rents low, creating uncertainty for landlords, who could see rents—and thus property values—plummet with the construction of a new skyscraper down the block. Thus, a constituency for comprehensive density restrictions that might temper this growth in major cities like New York City was born.

On the transportation front, the invention of the electric streetcar in the mid-1880s—and the rapid spread of new transit systems through roughly 1910—removed barriers to urban horizontal expansion. Often developed privately as part of a broader land development plan, streetcar lines soon stretched far outside cities and gave rise to streetcar suburbs, with apartments around stops gradually giving way to detached single-family homes.5 The democratization of the car, beginning in 1908, shifted this suburbanization into overdrive.

The Anglo-American pastoral ideal of a detached single-family house surrounded by a yard dates back at least to Jefferson, with home life characterized by privacy and domesticity.6 Yet when the modern American suburb first began to take shape in the post–Civil War period, it was largely restricted to the wealthiest by high transportation costs.7 With a car, many middle-class households were no longer restrained to living within walking distance of work or transit, resulting in the rapid development of strictly low-density residential subdivisions at the edges of nearly every American city. Suburbia was no longer the exclusive domain of wealthy elites.

In the same way, cars released working-class households—and the apartments they inhabit—from downtown, while trucks released industry—and the warehouses it required—from needing to cluster around traditional transportation hubs like ports and rail depots. This gave both apartments and industry the opportunity to decamp for cheap land in the suburbs, threatening the strict class and use segregation that had historically characterized suburbs.8

One way of dealing with this problem, from the point of view of an affluent homeowner concerned with change, was through restrictive covenants. These covenants were in many ways a kind of proto-zoning, placing tight restrictions on land use and densities—no corner groceries, no subdividing homes into apartments. Their provisions would control issues like landscaping and architectural aestheti...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Subscribe to Island Press

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Conclusion

- Appendix: What Zoning Isn’t

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Recommended Reading

- Index

- About the Author