- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Don Giovanni" Captured considers the life of a single opera, engaging with the entire history of its recorded performance.

Mozart's opera Don Giovanni has long inspired myths about eros and masculinity. Over time, its performance history has revealed a growing trend toward critique—an increasing effort on the part of performers and directors to highlight the violence and predatoriness of the libertine central character, alongside the suffering and resilience of his female victims.

In "Don Giovanni" Captured, Richard Will sets out to analyze more than a century's worth of recorded performances of the opera, tracing the ways it has changed from one performance to another and from one generation to the next. Will consults audio recordings, starting with wax cylinders and 78s, as well as video recordings, including DVDs, films, and streaming videos. As Will argues, recordings and other media shape our experience of opera as much as live performance does. Seen as a historical record, opera recordings are also a potent reminder of the refusal of works such as Don Giovanni to sit still. By choosing a work with such a rich and complex tradition of interpretation, Will helps us see Don Giovanni as a standard-bearer for evolving ideas about desire and power, both on and off the stage.

Mozart's opera Don Giovanni has long inspired myths about eros and masculinity. Over time, its performance history has revealed a growing trend toward critique—an increasing effort on the part of performers and directors to highlight the violence and predatoriness of the libertine central character, alongside the suffering and resilience of his female victims.

In "Don Giovanni" Captured, Richard Will sets out to analyze more than a century's worth of recorded performances of the opera, tracing the ways it has changed from one performance to another and from one generation to the next. Will consults audio recordings, starting with wax cylinders and 78s, as well as video recordings, including DVDs, films, and streaming videos. As Will argues, recordings and other media shape our experience of opera as much as live performance does. Seen as a historical record, opera recordings are also a potent reminder of the refusal of works such as Don Giovanni to sit still. By choosing a work with such a rich and complex tradition of interpretation, Will helps us see Don Giovanni as a standard-bearer for evolving ideas about desire and power, both on and off the stage.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access "Don Giovanni" Captured by Richard Will in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médias et arts de la scène & Musique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Clouds of Feeling

Excerpt Audio Recordings

CHAPTER ONE

Imagining Excerpts

The early recording industry loved the opera excerpt. Companies relied on opera to legitimate their enterprise, pitching records and playback equipment as a means of accessing high culture. Advertisements showed living rooms filled with star soloists, and to judge from the records, their “performances” were mostly of songs.1 The dominant formats of the era, the “short-playing” wax cylinder and the shellac 78 rpm disc, delivered individual numbers more elegantly than whole dramas, and the brief, emotionally concentrated vignette proved enduringly popular. From the late nineteenth century, when recording emerged, through to the 1940s, longer-playing formats fell flat and complete opera recordings remained a rarity. Among them was a single complete Don Giovanni, issued on twenty-three double-sided discs in 1936.2 Though an invaluable document, it barely registers against the several hundred excerpt recordings that were released for this opera alone.

Those recordings can tell us a lot about the performance of the parent opera. Mainly arias and small ensembles, they offer a kind of aural dramatis personae, a roster of characterizations undoubtedly reflective of stage practice, at least to an extent. The industry and the new field of record journalism promoted the connection, offering translations, synopses, and photographs to illuminate the original context of each selection. At the same time, excerpts have always done more than evoke complete operas, whether the printed numbers that have circulated since the earliest days of the genre or the recorded “highlights” that appear to this day. They bring to mind performers, occasions, places, moods, musical styles—a whole world of associations that may or may not have anything to do with a given opera, or indeed any opera. Where excerpts on record are concerned, consumers who were not operagoers (and many who were, for that matter) may well have heard Don Giovanni discs in terms of other kinds of music, or experiences surrounding the buying and playing of records themselves. As much as they preserve operatic performance practice, excerpt recordings also bear witness to a broader culture of lyrical expression and exchange, most of it vocal, and all of it mediated by evolving technologies and markets.

How to Read a Record

My own introduction to short-playing opera dates to the same period in the early 1990s when I was first trying to teach Don Giovanni (see the introduction). In the midst of debating which version to play for my students, I discovered the Offenbacher Mozart Collection at the University of Washington, an archive of over fifteen hundred cylinders and 78 rpm discs of the composer’s vocal music.3 Encompassing well-known recordings that have appeared in LP and CD transfers, along with many others that have not, it opened my ears to a diversity of interpretation no less striking (or daunting) than what I encountered in the full-length audio and video releases of the Mozart bicentennial years. This invaluable resource forms the basis for part I.

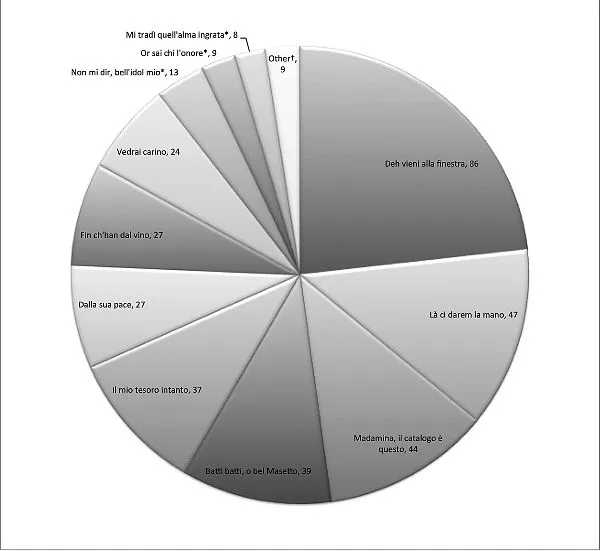

The contents of the collection’s 370 Don Giovanni recordings reveal something of the industry’s priorities. They lean heavily toward certain numbers, notably the arias of Don Giovanni, Don Ottavio, Leporello, and Zerlina, as well as the duettino for Don Giovanni and Zerlina, “Là ci darem la mano” (fig. 1.1). Donna Anna’s and Donna Elvira’s solos appear much less frequently, and other ensembles even less so. The proportions may differ somewhat from those found across all Don Giovanni releases of the era,4 but the chosen numbers suit both the general practices of the format and some specific preferences regarding this opera. They have much in common with the ballads and popular songs that dominate early recordings in general; in addition to being brief, they favor tuneful melodies, clear melody-and-accompaniment textures, and (mostly) straightforward romantic texts. They also support the industry’s interest in emphasizing love and comedy over violence and supernaturalism. As we shall see, the marketing vision for Don Giovanni could better accommodate the suave romancing of the title character’s Serenade, “Deh vieni alla finestra,” or the antic boasting of Leporello’s Catalogue Aria, “Madamina, il catalogo è questo,” than it could the rage and sorrow of the noblewomen’s arias or the complexities of Mozart’s ensembles.

FIGURE 1.1 Don Giovanni in the Offenbacher Mozart Collection. Totals include multiple recordings by the same singer(s), but not multiple releases of the same recording.

* Includes versions with and without the foregoing recitatives.

† Includes the ensembles “Ah taci ingiusto core” (two recordings), “O statua gentilissima” (2), and “Eh via buffone” (1); Leporello’s solo, “Notte e giorno faticar” (2); an excerpt of the act 1 finale, the menuetto (1); and an excerpt of the act 2 finale, “Già la mensa è preparata” (1).

The physical discs and cylinders suggest additional priorities, not all of them related to the parent opera. They came with comparatively little information, mere labels as opposed to the illustrated boxes and explanatory booklets that would accompany operas on LP and CD. Yet still they sought to direct listeners, especially discs, which proved the more enduring medium. Disc labels for opera, splashes of color against the solid background of the shellac, often signal the high-art pretensions of the contents (fig. 1.2). Several firms mixed modernism with neoclassicism, associating records with columned temples, lyres, and figures of myth (an angelic muse on Fonotipia’s labels, Romulus and Remus on Cetra’s). The images evoke cultivation and privilege, as does the frequent use of gold or silver lettering on a deep-colored background. The latter practice lends a rarified air even to Victor’s labels, with their homely drawing of Nipper the dog, and indeed Victor and its corporate descendants would use color to signal exclusivity well into the LP era, issuing opera and classical music on a special “Red Label.”

FIGURE 1.2 78 rpm disc labels, 1907–55

a. Giuseppe Anselmi, “Il mio tesoro intanto.” Fonotipia 62167, 1907. Courtesy Music Library Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries. Photograph by the author.

b. Elisabeth Schumann, “Schmäle, schmäle, lieber Junge” (“Batti batti, o bel Masetto”). Odeon 76726, 1917. Courtesy Music Library Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries. Photograph by the author.

c. Ezio Pinza, “Fin ch’han dal vino.” Victor 1467, 1930. Courtesy Music Library Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries. Photograph by the author.

d. Giuseppe Taddei, “Deh vieni alla finestra.” Cetra AT 0403, 1955. Courtesy Music Library Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries. Photograph by the author.

The texts of the disc labels convey more tangible information and still another set of priorities. The largest print names the company, drawing attention to its role as cultural curator. Next in prominence is most often the opera, sometimes set in large type or all caps (figs. 1.2a, 1.2b, and 1.2d). Companies may have thought the work titles would be more familiar than those of the individual numbers; along similar lines, where an aria or ensemble title appears first, it sometimes bears an attribution, as in “Serenata from Don Giovanni.” To this extent, the labels do highlight the parent opera; to purchase an opera record was to buy into a story or a stage event.5 On the other hand, it was also to invest in a singer, whose name and credentials generally overshadow those of accompanists or even composers. Many labels indicate voice types, and some identify cities or opera companies with which the soloists are associated (e.g., fig. 1.2a). By contrast, the composer’s name may be set in small type or parentheses, and the accompaniment reduced to a generic “piano” or “orchestra” (figs. 1.2b and 1.2c)—if it is mentioned at all (fig. 1.2a). Just as the content of early recordings revolved around song, so performance did around singers, and everyone else remains subsidiary through much of the short-playing era. Record company, selection, and soloist were the items the industry considered essential, the initial stimulus to the listener’s imagination.

Musical Companions

Programming combinations were a different kind of prompt. As short as they were, wax cylinders and the original single-sided discs sometimes included more than one selection: a 1909 Victor disc, featuring the baritone Antonio Scotti, follows Don Giovanni’s “Deh vieni alla finestra” with the equally brief “Quand’ero paggio” from Verdi’s Falstaff. Once the two-sided disc prevailed in the 1920s, nearly every selection came with a partner. Of course, the phonograph operator had the final say over what was heard and in what order, but two-sided discs invited consumers to think of multiple selections in relation to one another, selections that were usually performed by the same soloist.

Across the Offenbacher collection, Don Giovanni excerpts are most commonly paired with other music from Don Giovanni, especially other numbers for the same characters. About 20 percent of the recordings of “Deh vieni alla finestra” appear together with renditions of “Là ci darem la mano” or of Don Giovanni’s Champagne Aria, “Fin ch’han dal vino,” and roughly a third of recordings of Zerlina’s “Batti batti, o bel Masetto” and Don Ottavio’s “Il mio tesoro intanto” flip over to play the same characters’ “Vedrai carino” and “Dalla sua pace” (the other popular number, Leporello’s “Madamina, il catalogo è questo,” generally takes up both sides of a two-sided disc and thus appears by itself). Whether or not they were heard in sequence, two excerpts from the same opera point again toward the parent work, and two arias by the same character suggest a kind of profile, sometimes reinforced by attributions. When Maria Cebotari recorded “Batti batti, o bel Masetto” and “Vedrai carino” in 1941, Deutsche Grammophon subtitled each one “Arie der Zerlina,” as if they were elements in a characterization.

When Don Giovanni is matched with other sources, the choices differ by character. The arias of Zerlina and Don Ottavio tend to appear with like examples. The most common partner for “Batti batti, o bel Masetto” is Susanna’s “Deh vieni non tardar” from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, another pastoral love song for a buffa heroine; and for “Il mio tesoro intanto,” it is Tamino’s “Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön” from The Magic Flute, another romantic effusion for an idealistic aristocrat (tables 1.1 and 1.2). Both choices point up affinities between characters in different operas, as do, for the most part, discs featuring music by other composers. The non-Mozart selections paired with Zerlina’s and Don Ottavio’s arias all have romantic overtones of some...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Note to Readers

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- part i

- part ii

- part iii

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Discography

- Videography

- Bibliography

- Index