![]() New Worlds

New Worlds![]()

Rachmaninoff and the Celebrity Interview: A Selection of Documents from the American Press

SELECTED AND EDITED BY PHILIP ROSS BULLOCK

When, on 10 November 1918, Rachmaninoff sailed into New York on the SS Bergensfjord, it was not, of course, the first time he had visited the United States. He had earlier toured the country in 1909–10, premiering his newly composed Third Piano Concerto in New York on 28 November under the baton of Walter Damrosch (Gustav Mahler would famously conduct its second performance on 16 January). Although there was much about his trip that he disliked, Rachmaninoff came away with a number of more positive impressions. He had been struck by the quality of the American orchestras he heard, particularly in Boston, noted the high regard in which Tchaikovsky’s music was held, and—perhaps most crucially—appreciated the material rewards available to a successful virtuoso. As he confessed in an interview he gave to a musical journal on his return to Russia:

America bored me. Just think: I concertized very nearly every day for three months, playing nothing but my own works. My success was great, and I was obliged to give up to seven encores, which is a lot for local audiences. Audiences are remarkably cold, having been spoiled by tours by first-rate performers, and are always seeking something unusual, unlike what they have heard before. The local newspapers invariably mention how many times one is called back on to the stage, and for the general public, this is a measure of one’s talent.1

When, in 1917, Rachmaninoff was forced to abandon property and possessions in Soviet Russia and found himself providing for himself, his family, and many of his friends and colleagues, he rationally calculated that it was America, rather than Europe, that would provide for his extensive material needs.

A notable aspect of his life in the United States was the frequency with which he gave interviews to the press. It was not, admittedly, a genre in which he felt entirely comfortable. In January 1910, when he was still in America, the Russian critic Emil Medtner proposed a short study of his music. Rachmaninoff tactfully declined:

Dear Emil Karlovich,

I sincerely thank the editors of Musaget for their desire to publish a small book about my compositions.

Only, however flattering and pleasant the appearance of such a book would be to me, I must refrain from suggesting a critic who “knows” and “values” my works and who might write an article about me.

I must also refrain from suggesting “an extract from a letter of mine,” setting forth my profession de foi.

The only thing with which I can help the editors is the question of my portrait. Not only shall I indicate a fine portrait to the editors, but I shall even give them a portrait in my own possession, as soon as I return to Russia (in approximately five weeks).

So, please do not be offended by my refusals, but believe me once again when I say that while the appearance of such a book would be extremely pleasant to me, I simply would not wish to take an active part in its publication.

Yours sincerely,

S. Rachmaninoff.2

If Rachmaninoff had reservations about collaborating with a potentially sympathetic critic such as Medtner (whose brother, Nikolai, was a close friend and much admired fellow composer and pianist), he was yet more reticent about dealings with the press.

Later that year, however, Rachmaninoff found himself obliged to speak out. Writing from Berlin to the newspaper Russkiye vedomosti, he objected to an interview that had appeared in another paper, Utro Rossii, on 2 November. As he explained in his letter to Russkiye vedomosti:

Having read the article, I initially decided that I would not reply. Not because I found it in order and in accordance with the truth, but because it seems to me that few people pay attention to such interviews, and most important, few people believe them, and even if they do, then only one-tenth of what is contained in them. That, at least, is how I always treat them: I divide everything by ten and take into account the result. After all, even when your spoken words are treated entirely properly, there is a distinction between what you express in conversation and how this is expressed and published. After all, you speak in simple, conversational language, yet what you say cannot, of course, be recalled literally. This means that you can allow a degree of imagination on the part of the interviewer, who is guided by your main ideas or by the main contents of your conversation, yet conveys all of this in his, rather than your language. This is why sometimes, when one reads certain interviews, one never tires of being surprised: on the one hand, it is as if one really did say these things, on the other hand, it is as if one is hearing them for the first time.3

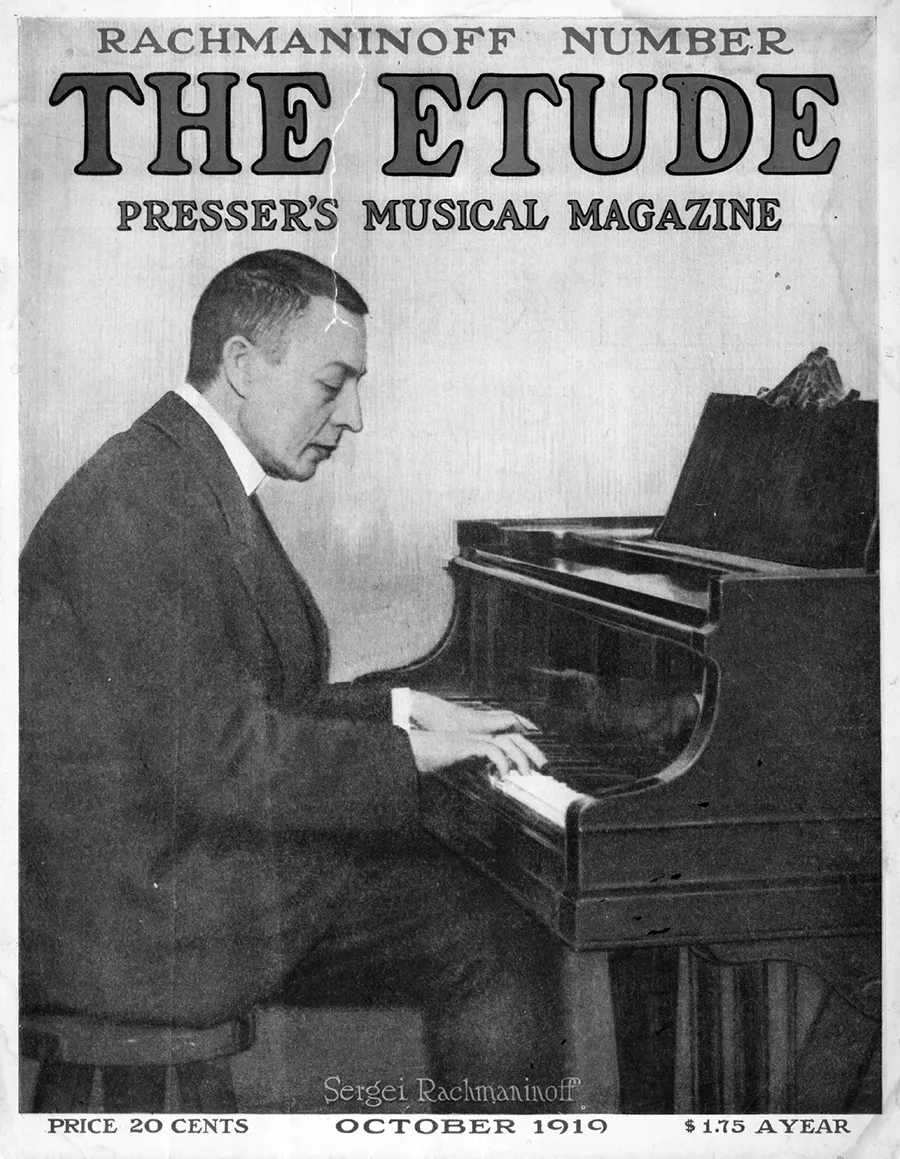

Figure 1. Front cover of The Etude, October 1919.

Yet the number of misrepresentations contained in the interview in Utro Rossii, as well as the fact that it had been published, forced Rachmaninoff to respond in print and to distance himself from the critical remarks about the Bolshoi Theater that he was alleged to have made to the newspaper’s correspondent.

If this incident confirmed Rachmaninoff’s often cautious attitude toward publicity, at least during his career in Russia,4 then his first American tour revealed to him the potential benefits of using the interview format to cultivate his celebrity, while still guarding his deeply felt sense of privacy. He gave at least four interviews during the three months he spent in America in 1909–10, and when he returned in 1918, he willingly responded to American interest in his music by giving regular interviews to a wide range of publications. He spoke to correspondents from musical periodicals, such as Musical America, Musical Courier, Musical Observer, Musical Opinion, The Musician, and especially The Etude, which published a special “Rachmaninoff Number” in October 1919 (Figure 1). As his fame spread through American cultural life, he appeared in Vanity Fair, Good Housekeeping, The New Yorker, and—posthumously—Vogue. His artistic views—as well as his regular comings-and-goings between Europe and North America—were reported in the New York Times, and in January 1931, the paper published one of his rare forays into politics. This was a letter—co-signed by Ivan Ostromyslensky and Ilya Tolstoy—attacking the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore for “his evasive attitude to the Communist grave-diggers of Russia” and lending “strong and unjust support to a group of professional murderers.”5

Unlike those notable tracts by other Russian émigré composers—Nikolai Medtner’s The Muse and Fashion (Muza i moda, 1935) and Igor Stravinsky’s The Poetics of Music (Poétique musicale sous forme de six leçons, 1942)—Rachmaninoff’s interviews cannot be interpreted as a coherent, categorical, or consistent profession de foi. Neither can his so-called Recollections (1934), the result of a series of conversations with Oskar von Riesemann. Rachmaninoff was aghast at the book’s initial draft, even paying for the proofs to be reset and insisting that the manuscript be revised so that “the entire responsibility for words that are supposedly mine should be borne by him instead.”6

Nonetheless, a number of common themes emerge in Rachmaninoff’s interviews. He is emphatic about his sense of Russianness and his place in the Russian musical tradition, something only heightened by his experience of emigration. He is enthusiastic about the level of musicianship to be found in the United States, while noting that many of its orchestras largely consist of European performers and tactfully avoiding commenting on American composers.7 His distaste for musical modernism is frankly expressed, although a rather more reflective attitude begins to emerge from 1926 onward, when he returned to composition and proved to be more receptive to contemporary influences than is sometimes appreciated. He repeatedly emphasizes the primacy of emotion, and the idea of music as an expression of a composer’s biography. He uses his reputation as a leading virtuoso pianist to comment on the importance of a strong technique and rigorous professional training (and offers a gracious and detailed commentary on how to approach the ubiquitous C-sharp Minor Prelude).

There is no doubting the sincerity of many of Rachmaninoff’s published statements, yet they should be treated with a degree of caution, too. When Basil Maine interviewed him for Musical Opinion in 1936, he observed that “his look was always that of a world-weary man. But I suspected that this was part of the façade that every public artist must devise for self-protection.”8 Rachmaninoff’s interviews were part of that façade too. Just as he embraced the new technologies of the piano-roll and acoustic recording (he rejected the radio, though) and signed to an exclusive relationship with Steinway pianos, he intuited that the celebrity interview could help him to court and cultivate the popular audiences on whom he depended financially, thereby bypassing those critics who dismissed his music as an indulgent hangover of late Romanticism. Rachmaninoff adroitly appealed to interest in a seemingly vanished age of great piano playing, as well as to a vision of a lost world of Russian gentry culture (comparisons with Chekhov and Bunin were routine at the time). This was a dialogue carried out with émigré Russian audiences too, so that it is instructive to compare the content and style of his American interviews with his reception in the publications that circulated in what was known as “Russia Abroad.” It is fascinating to see how Rachmaninoff represented his American life to his rather different European audiences; after all, he regularly returned to the “Old World” throughout the 1920s and 1930s, performing extensively across Western Europe, enjoying the company of close friends and family members, and eventually settling in the villa that he had built on the banks of Lake Lucerne.

Out of more than forty known interviews that Rachmaninoff gave throughout his life, eight are given here, all taken from American periodicals and publications.9 They are presented exactly as originally published and without further annotation or correction of errors of spelling or fact. Although individual phrases and sentences have often been cited in the critical and biographical literature, this is likely the first time that these interviews have been reproduced in full in English.10

“Modernism Is Rachmaninoff’s Bane,” Musical America 11/2 (20 November 1909): 23

Famous Russian Composer and Pianist No Friend to Methods of Strauss and Reger—Deplores Latter-Day Musical Sensationalism—Arduous Labors of a Disciple of Tschaikowsky

Sergei Rachmaninoff, the eminent Russian musician, has no ambition to be known as an ultra-modern composer. Emphatically the contrary.

“I have scant sympathy,” said he to a MUSICAL AMERICA interviewer, “with those who have allowed themselves to succumb to the wanton eccentricities of latter-day musical sensationalism. Unfortunately I cannot express myself as optimistic regarding the ultimate results of contemporaneous tendencies for I do not believe that future composers will manifest any desire to rid themselves of many obnoxious influences which have found their way into our art. The methods of Strauss and Reger have come to stay. But I, for one, shall steer clear of them.”

Americans will have an opportunity of judging Mr. Rachmaninoff’s compositions for themselves during his stay in this country.

“I shall remain in America until January 23,” said he, “playing with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the Russian Symphony, and possibly with some others. Among the most important of my works to be heard during my stay will be my new third piano concerto, and a symphonic poem ‘L’Isle des Morts,’ which was inspired by Böcklein’s well known picture of that name. At some of the recitals the ‘Preludes’ will be given.”

A report recently circulated that Mr. Rachmaninoff had studied under Tschaikowsky was declared by the composer to be untrue.

“If I am a pupil of that master it can be only figuratively speaking,” he observed; “true, I was acquainted with him for a number of years, during which time he displayed an interest in my compositions, which very frequently received the benefit of his criticism. But at the time of his death, I was only twenty-one. Inasmuch as, in my own works, I have followed his methods rather than those which are affected by most of my countrymen at present it may perhaps, however, be permissible for me to regard myself as a disciple of his. My regular teachers were Siloti, with whom I studied piano, and Arenski and Taniev, who instructed me in composition.”

According to his own confession Mr. Rachmaninoff is a hard worker, and the hours he devotes to composition are appallingly long. Most of his time is spent in Dresden, where he can work steadily, uninterrupted by his numerous acquaintances in Russia.

“During the progress of a new composition I can without exaggeration call myself a perfect slave,” he remarked. “Beginning at nine in the morning I allow myself no respite until after eleven in the evening. Just what such Herculean labor means to one of a nervous temperament may well be imagined. But something seems to drive me on until my task is completed.

“It may seem strange that though I am a pianist I truly abhor writing for that instrument, and experience far more trouble in this way than when composing for the orchestra or the voice. I consider the piano to be lacking in those varieties of tone color in which I delight.”

At the mention of Chopin in attempted refutation of this remark the Russian composer smiled. “Of course, of course,” he said, “but Chopin as well as Schumann, and Liszt, are the noteworthy exceptions. They are to my mind by far the greatest composers for the piano, and their wonderful treatment of it has never been surpassed. My opinions of Liszt in particular are of the most exalted. What beauty, what depth in his splendid orchestral conceptions! What a masterpiece in his ‘Faust’ symphony!”

Mr. Rachmaninoff considers a programmatic idea as essential in facilitating his creative labors. “A poem, a picture, something of a concrete nature at any rate, helps me immensely. There must be something before my...