Chapter 1

Journey to the centre of ancient Britain

The Orkney enlightenment

Like all the best stories, this one begins in a distant land, far away across the sea. In the islands of Orkney, to be precise. To say that Neolithic British ‘civilisation’ began at the northern edge of Great Britain and then spread south and west from there remains far too categoric a statement to make with any certainty. However, what we can say is that the magnificent stone structures that endure on Orkney date back to around 3000 BC and hence predate Stonehenge and, for that matter, most – though not all – of the stone circles and other ancient sites of Cumbria.

We know as much as we do about Neolithic Orkney in part because of the extraordinary discoveries made in the last two decades at the ongoing excavations on the Ness of Brodgar, which lies between the Neolithic circles of the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness on Orkney’s Mainland.

Speaking with an excitement married with a variety of certainty unusual in their profession, archaeologists told of the discoveries which effectively shattered the prevailing understanding of our prehistory at the time. Speaking in 2012, Orkney archaeologist Nick Card, who discovered the site at the Ness of Brodgar, said: ‘We need to turn the map of Britain upside down when we consider the Neolithic and shrug off our south-centric attitudes.’1 For what has been unearthed these recent years at the Ness of Brodgar is a quite extraordinary complex of buildings that appears to represent a huge ceremonial centre, comprising large buildings clearly designed to ‘make a statement’, and smaller dwellings. It appears to have served a central function in the ceremonial life of the wider Orcadian landscape with its nearby monumental stone circles and countless burial chambers, standing stones and other relics scattered throughout the archipelago.

The ongoing excavations at the Ness of Brodgar were featured in a 2016 BBC 2 series, Britain’s Ancient Capital – Secrets of Orkney. In the course of excavations that summer, charcoal fragments were found and carbon-dated to even earlier: 3512BC, or a whole millennium before Stonehenge. The series’ presenter, Neil Oliver, summed it up thus: ‘It’s beyond speculation that in the Neolithic, Orkney was the centre of something – an idea or a series of ideas, a way of living evolved here and its influence spread the length of the island of Britain.’

Once you accept that Orkney played a crucial role in the evolution of Neolithic culture you also have to accept certain other things as given. Most important among these is that some people in the early days of the new agriculturally-based society moved around a lot and, most importantly, that they must have moved around by boat. Just as Orkney became a hugely important centre in the Viking Age because of its central oceanic location, so must this have also been the case 4,000 and more years previously.

We can say this because all the evidence points to the Neolithic inhabitants of Orkney having arrived from the Scottish mainland with their domestic animals and, although sea levels were most probably rather lower then, they would still have had to cross turbulent open waters. Furthermore, if Orkney was the geographic seat of a strand of Neolithic civilisation, then other seas would have needed to be crossed to enable the ‘export’ of that civilisation to other parts of the British Isles. Some have dubbed this aspect of Neolithic life the ‘cult of the stone circle’. However it is wrong to infer from this that the first stone circles were built on Orkney. Although stone monuments are by their very nature very difficult to date, associated archaeological evidence suggests that Long Meg and Her Daughters may be at least as old.

Of particular importance to the story told in this book is the fact that the numerous spectacular finds made at the ongoing excavations at the Ness of Brodgar include fragments of material originating from the so-called Cumbrian axe factory. Although the total number of stone axes found across Orkney is modest, a single flake of Cumbrian tuff was found at the Ness. Neolithic Cumbrian axes were ‘tuff’ in origin and tough by nature, hewn from seams of volcanic greenstone tuff high in the Langdale Pikes and around Scafell Pike in the central Lake District fells.

Axes made from Cumbrian tuff were of such exceptional quality that some appear to have been used for ceremonial purposes only, rather than for chopping wood or butchery. They are found all over the British Isles and beyond, and appear to have made up close to a third of total axe production in the British Isles. A great many have been found to the east of the Pennines, in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, and so a theme that will recur in this book is the idea that our modern trans-Pennine routes – specifically via the passes of Hartside, via Alston; Stainmore (today’s A66); the Eden Valley and Wensleydale route; and the Aire Gap (A65) – may well have their origins way back in these times.

So, when the Romans built their road network they would in many cases have simply followed much earlier established trading routes and there is good evidence that some such routes dated back to Neolithic times when they were punctuated by stone monuments that served important cultural roles in the society of the time. Karen Griffiths, Interpretation Officer at the Yorkshire Dales National Park, writes in her blog: ‘The concentration and complexity of some of these ritual places tells us that the communities that built them were able to invest a great deal of time and resources in them. The placing of the imposing avenue of standing stones at Shap, at the entrance to the geological routeway through the hills, seems to be no coincidence.’2

She continues: ‘By the Later Neolithic, long-established lines of exchange were in use. Scarce commodities like salt and polished stone axes had value and were moved long distances. Axe roughouts from “factories” in Great Langdale, in the Lake District, have been found the length and breadth of the country. The rough-outs were polished up into their final beautiful forms some distance from where they were quarried. Sea routes seem to have been the main way these axes travelled such long distances and roughouts have been found at the Humber Estuary and along the west coast of Cumbria. There is also a concentration of axe rough-outs around Penrith to the north and in the Aire Valley to the south. It isn’t too much of a stretch of the imagination to see the Lune Gap as lying along one of the southerly routes for these sought-after axes and other essentials like salt.’

Griffiths suggests that controlling access to the route or to the items which moved along it would have given communities around Shap status and power. ‘Erecting a grand processional avenue would have been a reflection of that status. Power and privilege was reinforced for those who participated in whatever rituals took place along the avenue.’

Moving forward to Roman times, not all Roman roads have been adopted by modern highway-builders: High Street – which runs from Ambleside (not far from the axe factories) to Penrith – traverses a high but relatively gentle ridge and remains popular with walkers. It also passes right through a major site of stone circles and cairns, sitting at an ancient crossroads and offering as clear evidence as you’d wish to find of much earlier traffic. Beyond Penrith, with its mighty henges of Mayburgh and King Arthur’s Round Table – as you head towards the old Roman route up Hartside – are other Neolithic remains, including the magnificent Long Meg and Her Daughters, Little Meg and Glassonby, and the cluster of circles in Broomrigg Plantation, near Kirkoswald.

Join the dots between these ancient sites and what begins to emerge is the idea of a network of trading routes over which one of the commodities traded would have been Cumbrian axeheads. So, we can start to imagine that the various collections of Neolithic and Bronze Age remains east of the Cumbrian mountains may have reflected not just the location of early farming settlements but also the routes that connected those settlements.

But what about the early remains that lie to the west of the mountains, on the Cumbrian coastal strip? Although less dramatic or visible than the magnificent circles and henges, which lie mostly (though by no means exclusively) towards the eastern side of the central Lake District massif, the settlement evidence on the western flanks of that massif offers extraordinary insight into how these early agriculturalists may have lived. The remains of settlements can be found at regular intervals, and many are inscribed on the Historic England register of monuments, which notes that the land above the coastal strip comprises ‘one of the best recorded upland areas in England’, with Tongue How (south of Ennerdale) bestowed with ‘prehistoric stone hut circle settlements, field systems, funerary cairns, cemetery and cairnfield, Romano-British farmstead, shieling and lynchets’. Although much of the settlement activity came in the later Bronze Age, there is also evidence of earlier settlement coincident with the start of the axe quarrying in Langdale.3

The Neolithic axe ‘rough-outs’ from Langdale would have passed through these settlement areas on their way to the Cumbrian coast, some for ‘finishing’ and some to make their way by sea as far as Ireland and Orkney. Excavations at various sites on that coastal strip have yielded artefacts, including axe rough-outs, suggesting that the ‘value-added’ function in the stone axe industry – the grinding and polishing – may have been concentrated here (and in other lowland locations at the edge of the fells). The North West Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment catalogues archaeological finds from the length of the coastline, including a number of key locations at which axe remains have been found. Among these locations is Ehenside Tarn, a small body of water largely drained in the mid-nineteenth century, when it yielded up axes, a grinding stone, dugout canoe and possible paddle. A polished axe and numerous stone tools were found at sites near Askham-in-Furness and Barrow, and there was also evidence of at least another four henges and circles along this strip.4

In a paper entitled Polished axes, Petroglyphs and Pathways: A study of the mobility of Neolithic people in Cumbria, Peter Style revisits (in an undated dissertation thought to have been written around 2010) the whole subject of Cumbrian axeheads and the movement of people. He identifies concentrations of axe finds around Derwentwater, along the banks of the Eden and the Eamont and on the coast at the Solway Firth, Seascale, Drigg and the previously mentioned sites in Furness. It was to these areas, and to the polishing ‘workshop’ at Kell Bank, near Seascale, that the rough-outs were transported for finishing.5 This process of movement and transport was of particular relevance to my visit to meet the Cumbrian axe factory expert, Mark Edmonds, in Orkney.

Of course, it would be one thing to transport some rough-outs by boat in Neolithic times; quite another to transport cattle. Which brings us to the inevitable question: what kind of boats did these people build and sail? Mark Edmonds believes they must have been substantial, but that would not be enough to guarantee the survival of any traces of them across thousands of years. Similarly, where are the wooden axe handles? Where are the wooden roof timbers at the surviving stone hut foundations? Where are the heftier timbers that may have supported roofs above some of the cairn circles? In a paper in the 2013 publication, The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age, Benjamin W Roberts does cite one example of a surviving seagoing boat: ‘The rare excavation of shipwrecks such as the Dover boat […] certainly demonstrates that vessels of sufficient size existed when cross-Channel connections were established in the early second Millennium BC.’6

While this may have been later than when the first settlers crossed the Pentland Firth to Orkney, Roberts cites Needham 2009 as his source and this original work refers to a re-emer-gence of sea links following a period of relative isolation in the British Isles, during which a distinct ‘local’ culture appears to have evolved. Given that the Dover Bronze Age boat is claimed to be ‘the world’s oldest known seagoing boat’, it seems reasonable to infer that similar seagoing vessels might quite plausibly have existed for hundreds of years prior to the date attributed to the Dover Boat after it was found by construction workers on the A20 in 1992. The boat is now on display in a customised room at the Dover Museum, whose description states: ‘The workers, who were working alongside archaeologists from the Canterbury Archaeological Trust, uncovered the remains of a large and well-preserved prehistoric boat. This was a transformative discovery: archaeologists estimate the boat would have been in use around 1500 BC, during the Bronze Age. The archaeologists were aware that past attempts at excavating similar boats in one piece had been unsuccessful. Consequently, a decision was taken to cut the boat into sections and reassemble it afterwards. It was also necessary to leave an unknown part of the boat underground as its burial site stretched out towards buildings and excavating close to these buildings would have been too dangerous. After nearly a month of excavation a 9.5-metre length of the boat was successfully recovered and has since been marvellously preserved.’

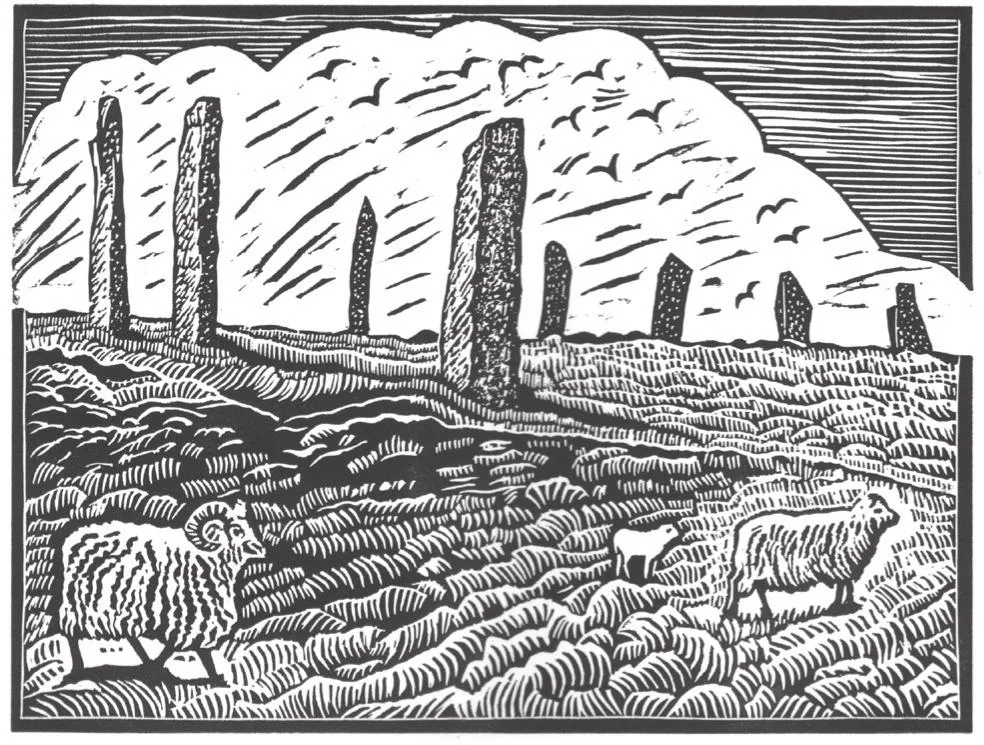

The Dover boat is special because it was found substantially intact, but it is by no means unique: Heritage Daily says there are nine others found in Britain, though these comprise fragments, rather than whole boats. Remnants of three such boats were found near Hull, thirty years previously. They exhibit a significant degree of complexity in their construction, which comprised oak planks ‘sewn’ together using withies. The structure was several metres long and was braced by cross-members and the gaps caulked with wax to seal it. Heritage Daily7 says: ‘It must be said that the construction techniques used to create these types of boats are astounding and Renfrew and Bahn8 agree, saying “in perhaps no other area of pre-industrial technology did the world’s craftspeople achieve such mastery as in the building of wooden vessels…”.’ This is the context in which I find myself weighing up Mark Edmonds’s wry smile when we talk about the ‘Neolithic boat’ reconstructed for the BBC series Britain’s Ancient Capital: Secrets of Orkney. My wife Linda and I meet Edmonds on a perfect Orkney midsummer day, the high sun exaggerating the lush green of the rolling pastoral Orkney landscape, relaxing beneath an unusually windless sky. The world is emerging a little sleepily from lockdown when we meet at the car park at the Ring of Brodgar, Orkney’s premier stone circle. My initial thoughts on learning that the world’s prime authority on Cumbrian stone axes was a Professor at York was that it should be a pretty ‘easy fix’. The visit would be a mere 40 minutes on the train and a bus out to the university. I had, of course, failed to grasp the crucial word ‘Emeritus’ in his title – otherwise known as an academic licence to roam in semi-retirement. Not that Mark looks particularly like a retired man of leisure: in fact, he is every bit the part of the working archaeologist, clad in denim, high-vis jacket, and with a fine head of straw-grey, curly hair.

We are standing beneath one of the towering Stones of Stenness – where else could a Neolithic expert reasonably choose to be? But just being there does not mean that you necessarily have to swim with the crowd on all matters. We quickly find ourselves discussing the boat recreated especially for the BBC series. Its structure comprised lengths of pliable willow covered in animal hide. It was flimsy and, though the team did manage somehow to row it across the Pentland Firth to the mainland, Mark, for one, struggles to imagine heavy cattle aboard a rather fragile vessel of skins. While this reproduction is viable, there would surely have also been more sturdy vessels: ‘There’s just a flow of people back and forth between the isles and up and down the Irish Sea: these trips are not to be sneezed at, even now, but we know that they happened because we have a number of stone artefacts in Orkney that came from mainland Scotland, the Western Isles and from other parts of the country. They must have had better boats than this – the fact that we haven’t found one is neither here nor there.’ Well, why would you find the remains of a five-thousand-year-old boat? Organic matter is the scarce resource that archaeologists yearn to get their hands on so as to put dates upon things that are excavated. The manner in which it has been possible to attach dates to the extensive settlement on the Ness of Brodgar and place Orkney ‘civilisation’ before that of Stonehenge is the exception rather than the rule; the Dover Boat is exceptional; ancient human corpses dug from peat bogs with stomachs still full of undigested food are exceptional.

What does survive is generally fragmentary, though Mark cites the finding of a large oak plank, buried in the sil...