- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Style: An Approach to Appreciating Theatre

About this book

Style: An Approach to Appreciating Theatre offers brief, readable chapters about the basics of theatre as a starting point for discussion, and provides new adaptations of classic plays that are both accessible to students learning about theatre and fit for production.

In this text, style is the word used to describe the various ways in which theatre is done in real space and time by humans in the physical presence of other humans. The book uses style, the "liveness" of theatre that makes it distinct from literature or history, as a lens to see how playwrights, directors, designers, and actors bring scripts to life on stage. Rather than focusing on theatre history or literary script analysis, it emphasizes actual theatrical production through examples and explores playscripts illustrating four theatrical styles: Realism, Theatricalism, Expressionism, and Classicism. Susan Glaspell's Realistic play Trifles is presented as written, while The Insect Play by the Brothers ?apek, The Hairy Ape by Eugene O'Neill, and Antigone by Sophocles are original, full-length adaptions.

Style: An Approach to Appreciating Theatre is the perfect resource for students of Theatre Appreciation, Introduction to Theatre, Theatrical Design, and Stagecraft courses.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1 Introduction

Drama or Theatre?

Drama

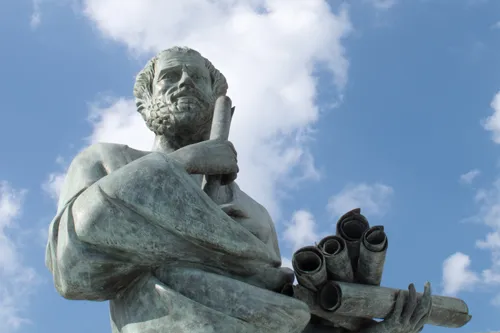

Aristotle

- Plot—the events that occur onstage in the play. You might also include events that occur offstage (such as the death of Romeo’s mother), but you wouldn’t include things that happened before the events of the play or that you could imagine happening afterwards. Willie Loman kills himself at the end of Death of a Salesman. We don’t see his suicide, but we could include that as the climax of the plot of the play. We couldn’t include Willie’s childhood or what his family might do after the funeral at the end of the play. Aristotle considered plot the most important of the six elements.

- Character—the agents of the action of the play. Their decisions, words, and actions make the plot happen.

- Language—the words the characters use. This would include specific word choice (having a character say, “Let’s get outta here” instead of “Let’s go”) as well as overall style of language. Some plays are meant to seem like everyday life, so those characters would speak using words and phrases appropriate to the setting of the play. Other plays use language that’s very flowery, or poetic, or somehow unlike the way people “really talk.” At the climax of Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones, when Yoda says, “Around the survivors a perimeter create,” that’s not the way people normally talk. But it is the way Yoda talks in the Star Wars universe. It’s not a flaw; it’s a choice.

- Theme—the larger ideas of the play. This goes beyond plot. A theme of Romeo and Juliet, for example, wouldn’t be “Romeo and Juliet fall in love” or “Romeo’s mother dies.” The play is about passionate love, family loyalties, unintended and unexpected consequences, gang violence, murder, suicide, death. These are some of the thematic issues the play grapples with. It’s better to understand theme in terms of ideas and questions rather than messages and answers. Try not to think of theme as “the moral of the story,” like “Don’t judge a book by its cover.” Good plays tend to ask questions, requiring the audience to think, rather than providing easy answers.

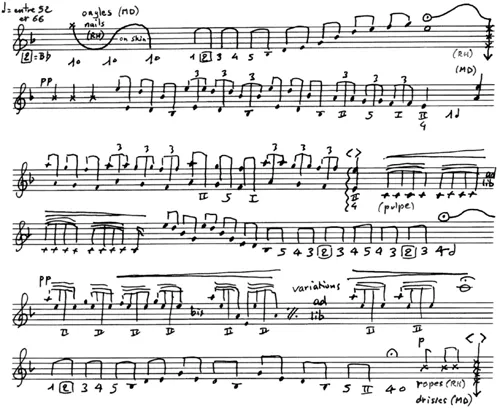

- Rhythm—the tempo and “feel” of the play in performance. Rhythm is found in the actions of the characters as well as the language they use. Is a scene in the play fast or slow? Does it build in intensity over time? Do characters move in graceful arcs or pace frantically? Like we discussed with a piece of music, a play has rhythm and mood—really, a variety of rhythms and moods. And, like music, rhythm includes the sounds we hear when watching a play: things like the actor’s voices, sound effects, and music. In fact, Aristotle used the term “music” for this element, and was mostly referring to actual music. In modern usage, we’ve broadened the term.

- Spectacle—everything you see and experience when you attend a play. This includes of course sets, costumes, makeup, lighting, props—all things we’ll discuss later. But it also includes things you might not immediately think of. Imagine yourself sitting in a theatre, watching a play. What is literally in your field of vision besides the things mentioned above? The stage itself. The walls of the theatre building. The seats. Other audience members. What can you hear? Smell? Everything you experience while watching the play is part of the overall spectacle. Again, this is very much connected to the idea that theatre is essentially about live performance.

Theatre

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Prologue

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Style

- 3 Realism

- 4 Theatricalism

- 5 Expressionism

- 6 Classicism

- 7 Musical Theatre

- 8 The Playwright

- 9 The Director

- 10 The Designers

- 11 The Actor and Other Collaborators

- Bibliography

- Glossary

- Index