![]()

FORK NINE – A THIRD MENTOR GIVES ME A CHANCE

On the road less traveled, I stumbled into Fork Nine. Once again, through pure luck, I had found a unit at the right time. I had been exceedingly fortunate to find a unit with a vacancy for a colonel and a command that would take me. Sills, although he had not known me personally, gave me an opportunity to serve in a large unit, approximately 500 strong. “Wow!”

As I predicted, the staff members of the comptroller’s office were highly competent and gave me the support I needed to perform my duties. The real challenge came with the need to commute from my house in Blacksburg to Fort Belvoir. On a good driving day, it required a little over four hours. In addition, as a member of the general’s staff, I had a monthly staff meeting to attend.

The armory of the 310th Theater Army Area Command, where my office was located, was near Davison Army Airfield. I received permission to fly into the airfield and soon began landing there. I bought a used car to keep at the airfield. The first car I purchased looked good, and it was promptly stolen. I did not make that mistake twice; for my next purchase, I bought a battered clunker that looked terrible, but I kept a new battery in it and a good set of tires. No thief would ever be caught driving such a disreputable car, and I had no further trouble. At the armory, I parked it next to the car driven by Colonel Willoughby, which happened to be a Jaguar. Yes, you get the picture.

Brigadier General Montgomery exiting his Cessna 182

The colonels who served on the staff of the 310th at that time had high-ranking positions in the government and were very competent. Many had risen through the ranks of the 310th, and as a consequence, had little or no opportunity for command experience … other than being the heads of various sections in that unit. But I had command experience, and against that competition, I looked good. Almost immediately, Metz named me the chief of staff. That role called for much responsibility. In the absence of the commanding general, the chief of staff chairs the meetings of the staff, carries out the directions of the commanding general, and seeks to keep the various sections working together and the unit functioning. It is a command position in every sense of the word. The 310th had two subordinate units commanded by colonels and a couple of companies that also drilled in the armory at Fort Belvoir. This organization was similar to the structure I had observed during my stay at Fort Mason.

Reassignments now occurred. Metz became the commander of another Army unit with the responsibility for other reserve units and won his second star to become a major general. Brigadier General Harry Treadway, whom I knew from the 80th Division, transferred to the 310th and picked up his second star in the process. I moved into the position of deputy commander of the unit. Shortly thereafter, the U.S. Army Headquarters sent my name forward to the U.S. Senate for promotion to brigadier general, and when I received its affirmative vote, I won my promotion. So in 1977, after twenty-five years as a commissioned officer, I made my first star. I was behind my officer group in promotions, but at age forty-seven, I remained spry and, hopefully, ready to perform.

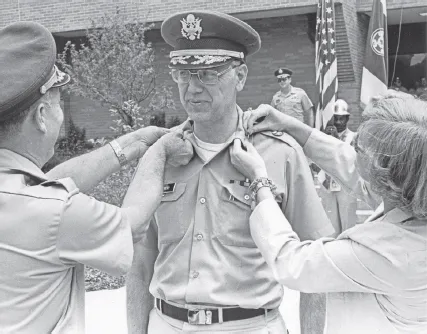

Major General Treadway, in command of the 310th TAACOM, and Mary Montgomery pin stars on Brigadier General Montgomery during promotion ceremony.

Shortly after my confirmation to general, I received orders to report to Washington, D.C. for a one-week orientation session for all newly appointed general officers. We called it “charm school.” There we received the latest material on command and control issues in the Army. The course also had a segment on personal conduct expected of the new generals:

1.Keep control of your drinking.

2.Avoid a personal relationship with members of the opposite gender within your command.

3.Do not use government aircraft for personal use.

We shortened these rules to no booze, no broads, no high flying.

Brigadier General Montgomery, official photo

Up until this time, the 310th had been a relaxed unit where nothing much happened. Many said the unit was a great country club. A member of that era told me that some of the officers took a nip during drills. That lax condition ended in 1977 when FORSCOM gave the 310th a new mission to reinforce NATO in Europe. I arrived just in time to be a part of this new mission. While I cannot attest that no drinking occurred thereafter, the pace intensified, and the country club atmosphere disappeared. FORSCOM aligned many reserve units to be in the command structure of the 310th upon mobilization. This assignment of units and missions was part of the CAPSTONE strategy program of FORSCOM.

When the Allies assigned sectors of Germany to the U.S. at the end of WWII, the U.S. Army had the responsibility for the southern sector of Germany. The northern plains of Germany had little in the way of natural defense barriers, except the rivers that flowed south to north. The northern sector had been assigned to Great Britain to defend with the help of Belgium and the Netherlands. NATO wanted more forces in that northern sector, and FORSCOM complied by naming the U.S. Army III Corps, headquartered in Fort Hood, Texas, for that role. But III Corps could not operate without support, and the 310th was tasked with the responsibility for the equipment supply and maintenance of III Corps. In addition, we were to provide those same services to other U.S. Army units all the way to the North Sea. Consequently, the command structure of the 310th grew with many new units, which upon activation would have a strength of about 18,000 personnel. To fulfill our new responsibilities, the 310th now commanded units of engineers to maintain the roads and buildings, military police, stevedores, truck companies, and quartermaster, signal and anti-aircraft units, plus many, many more. The 310th had embarked on an entirely new mission and new direction.

During our first year in Europe, III Corps and the 310th occupied an old WWI prisoner of war facility that Germany had previously operated near the border with the Netherlands. Conditions were spartan. Our second year was spent in Mönchengladbach on the east side of the Rhine River near the border with the Netherlands. There, the Army leased a former knitting mill where we not only trained, but we slept as well. The enlisted personnel had their meals there, too. Here we had ideal training facilities.

Typically, the 310th traveled to Europe by chartered aircraft. For the most part, the trips proved routine. Trouble developed in 1981. On the trip over, a security guard stopped one of our officers who carried a bottle of whisky in his bag. He elected not to drop the bottle in a waste can. Instead, displaying the initiative one expected from an Army officer, he gathered his friends, and they all left the terminal. They found a spot under a shade tree where they soon eliminated the problem of a full bottle of whisky. This slightly tipsy crew passed through security without incident, proving there are more ways than one to be high in an airplane.

Starting in 1979, the 310th and associated units began training in a variety of exercises in Europe each year. In one year, it would be a Map Exercise (MAPEX), where the unit participated in on-paper exercises. The next year the unit would join in REFORGER, the exercise to return forces to Germany. The 310th continued this role until the U.S.S.R. broke apart, soon after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. In addition, we received a task to work with the European countries on a project called “Host Nation Support.” The 310th received this mission because the Regular Army forces had too many other responsibilities. In this role, the unit interfaced with Army Headquarters for the Netherlands, Belgium, Great Britain, and West Germany. The main objective was to help bring forward supplies or to permit such supplies to flow to the front and thus to III Corps. In a state of war, such agreements would have been invaluable for the handling of supplies and reinforcements in a timely manner.

Little did we know what a nightmare awaited us on the return trip to the States. On Friday, the morning of our departure, we rose at 0600 and boarded buses. Upon arriving at the airfield, we discovered the air traffic controllers had called a strike. Travel to the U.S. slowed or ceased. Our pilots found they could not fly the usual great circle flight path past Iceland, Greenland, and Labrador. The controllers who did elect to work directed us to take a southern route. Eventually, the plane flew with its first stop in Ireland. After a long wait on the ground, we flew to the Azores, arriving Saturday night. I remember arranging a box dinner for our contingent with the Air Force duty officer. Later in the night we took off again, this time flying to an air base in New Jersey. As we made the approach to the field, one of our officers led the weary troops in singing songs – well, not all of them were bawdy. From there, we had about a seven-hour bus ride to the armory at Fort Belvoir. After reaching the armory, we still had to travel to our respective homes. By the time I arrived home late on Sunday night, I looked and smelled every bit as well as you might imagine I did.

I wanted the 310th to have an opportunity to grow its own high-ranking officers. Why should a Treadway or Montgomery come from other units to staff the 310th as commanding generals? I reasoned the way to do so would be to develop a strong cadre of officers who could step into such roles. I put out the word that officers needed to have completed or be enrolled in the Army War College or an equivalent course to be a colonel in this outfit. Also, personnel needed command experience. The senior officers had good common sense, and they met the challenge. By the time I retired, all the colonels on staff, with one exception, had completed the Army War College. This vision soon started to bear fruit. The 310th now provided general officers for itself and other commands. From the ranks of the 310th came Lieutenant General Tom Plewes and other generals, to include Herb Quinn, Robert Diamond, Robert Ruth, Robert Sullivan, Jeff Henderson, and Alvin Bryant.

I continued to try to find ways to develop the officers of the 310th. I learned that the wartime mission of the 510th Field Depot, a reserve unit in Maryland, was to provide a short-term storage point for supplies not immediately needed on the battlefield. I wanted that unit as part of the command structure of the 310th in order to offer another location to train colonels and other personnel. I had the objective; now I needed to reach it. First, I visited officers in my higher headquarters, the U.S. First Army. I was told to take the issue up with FORSCOM. Needless to say, I received a good lesson in how to work with higher headquarters. But no one could fault the logic of the situation, as the 310th and the 510th were both logistical units. Eventually, the 510th became a subordinate unit of the 310th. With more positions available to train personnel, the road became easier to prepare general officers.

General Treadway did not like to visit First Army Headquarters, to which the 310th reported. However, I tried to develop a relationship with the deputy major general and other staff officers of the commanding general, including the G-1 (head of personnel matters) and the G-3 (head of operations and training). Also, First Army assigned a full colonel to the 310th as a liaison officer. He served as the eyes and voice of First Army, but he could be convinced to see events through the eyes of the Reserve. I never forgot his role or his power.

After four years, the commander of the 310th typically moved on unless given an extension of time. General Treadway announced that he wanted to be extended. However, his continuation would mean I could not move up. But Treadway did not know the personnel in First Army headquarters, and I did. I discussed with the deputy commanding general of First Army, Major General Vince Russo, Treadway’s desire and my interest in taking over the unit. Also, I alerted the liaison officer to what was going on. The liaison officer and other officers in First Army observed that I had become the driving force in the preparation of the unit for its wartime mission. Ultimately, First Army decision makers decided that Treadway should complete a regular tour without extension and retire. In 1982 when Treadway retired, First Army named me the commander. Colonel Pete Cox from the 80th Division followed me into the role of deputy.

Lieutenant General Rosenblum officiates at the promotion ceremo...