- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

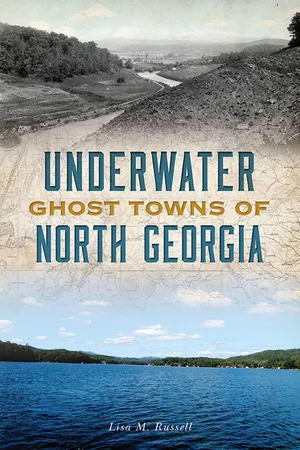

Underwater Ghost Towns of North Georgia

About this book

An archeologist reveals the mysterious world that disappeared under North Georgia's man-made lakes in this fascinating history.

North Georgia has more than forty lakes, and not one is natural. The state's controversial decision to dam the region's rivers for power and water supply changed the landscape forever. Lost communities, forgotten crossroads, dissolving racetracks and even entire towns disappeared, with remnants occasionally peeking up from the depths during times of extreme drought.

The creation of Lake Lanier displaced more than seven hundred families. During the construction of Lake Chatuge, busloads of schoolboys were brought in to help disinter graves for the community's cemetery relocation. Contractors clearing land for the development of Lake Hartwell met with seventy-eight-year-old Eliza Brock wielding a shotgun and warning the men off her property. Georgia historian and archeologist Lisa Russell dives into the history hidden beneath North Georgia's lakes.

North Georgia has more than forty lakes, and not one is natural. The state's controversial decision to dam the region's rivers for power and water supply changed the landscape forever. Lost communities, forgotten crossroads, dissolving racetracks and even entire towns disappeared, with remnants occasionally peeking up from the depths during times of extreme drought.

The creation of Lake Lanier displaced more than seven hundred families. During the construction of Lake Chatuge, busloads of schoolboys were brought in to help disinter graves for the community's cemetery relocation. Contractors clearing land for the development of Lake Hartwell met with seventy-eight-year-old Eliza Brock wielding a shotgun and warning the men off her property. Georgia historian and archeologist Lisa Russell dives into the history hidden beneath North Georgia's lakes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Underwater Ghost Towns of North Georgia by Lisa M Russell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THE ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS LAKES

1

THE ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) improved navigation on U.S. waterways. It has served as part of the army since the American Revolution. The Continental Congress organized the Corps to assist General Washington, and the organization is still part of the U.S. Army.29

The USACE, named in 1802, had a larger mission between 1900 and the 1930s, flood control. The Corps was required to benefit the national economy and include waterway navigation. While the Corps manages hundreds of multipurpose dam projects today, it ambled along in 1918 with its first hydroelectric project at Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Thus began the big dam era for the Corps.30

The USACE and hydroelectric power helped usher in the New South. The government infused the agrarian economy with federal monies to build up the region beginning in the Depression through World War II. The South Atlantic Division (SAD) of the USACE has four major themes, according to The History of the South Atlantic Division of the US Army Corps of Engineers, 1945–2011: military support, environmental protection and restoration, civil works and management leadership.31 Mistakes were made over the fifty years, but the USACE was steadfast in its mission of flood control, hydroelectric generation and navigation. The original purpose of the Corps was not to ensure water supply or create places for recreation, but those undertakings grew in importance.32

After the USACE built and supplied the war effort and helped with a postwar deconstruction of military installments, it returned to its first love of water control. Postwar Georgia, along with the rest of the Southeast, took baby steps toward environmental concerns, and the Corps moved to a more balanced approach. Environmental issues and economic benefits were growing concerns. Increased water use and environmental impact became obvious in the 1960s and 1970s. No major construction in the South Atlantic Division has been planned for over twenty years. The Corps now focuses on maintenance and environmental restoration.

The USACE began building dams and forming reservoirs in Georgia for navigation and flood control in the 1940s and 1950s under the Flood Control Act of 1944 and the Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Act of 1954.33 The reasons for the dams and lake have evolved. In 1950, Allatoona Dam was the first USACE project completed in North Georgia. It was followed by the Clarks Hill project in 1953, later renamed for J. Strom Thurmond. Lake Sidney Lanier began and was completed in 1957 with great pomp and circumstance. Lake Hartwell was filled with controversy in 1962. Carters Lake, the deepest Georgia lake, delivered the area from flooding in 1977. The Corps stopped building dams in 1985.

Just as the USACE evolved from a navigation and building wing of the U.S. Army, the reservoir projects changed in scope and purpose. The History of the South Atlantic Division of the US Army Corps stated, “No attention was paid to adverse effects to the land or fish and wildlife except as it involved a federally protected preserve.”34 The division had specific objectives: flood control and regional development. The USACE outsourced jobs that did not fit the mission. Archaeologists were hired to relocate cemeteries. The forestry division was utilized. The Corps saw no need to focus on biology, archaeology or forestry.35

Ignorant of the environmental impact of human-made lakes in the 1940s and 1950s—when most of the work was completed—in more recent years, the Corps has become environmentally responsible, reversing any damage caused by these reservoirs. The USACE also has cooperated with the more recent looter’s law protecting the historic remains when drought pulls back the waters and exposes lost communities. Steep fines discourage relic hunters from scavenging the lakes’ secrets.

Without breaking any laws, let’s dive deep into each lake and the communities that once thrived under the lakes managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Imagine a time in the ghostly past when North Georgia was filled with natural rivers and the souls who once thrived along the banks.

2

ALLATOONA LAKE

1950

History-minded Georgians and visiting historians from other States are preparing today for a final pilgrimage to a soon-to-be-submerged land where some of the lustiest, liveliest dramas of the past were played out.

—Celestine Sibley

Allatoona has more identifiable towns underneath its waters than all the great lakes of North Georgia. Remnants of the lost towns of Etowah and Allatoona lie above the water line. Until recently, Abernathyville was hidden. The Etowah Valley Historical Society has unearthed the existence of a community that lies just off the shores of the lake. Abernathyville lies just below the Old Macedonia Cemetery in Bartow County. Allatoona has been the subject of archaeological studies that reveal a civilization that predates these forgotten towns.

ABERNATHYVILLE (OLD MACEDONIA COMMUNITY)

He uncoiled the cords that guarded his weathered wallet and paid the man at the Cartersville News. He apologized, “The cold weather has kept me in, or I would have been down earlier to settle my subscription.” The seventyeight-year-old bewhiskered Bardy Larkin Abernathy sat down on a bright March morning in the newspaper office and bragged, “I was one of the first subscribers to the newspapers in this town.” He continued, “I took the old Standard and Express and all of the papers that have come on after it right straight along to now, and I can’t begin to do without your paper, that is right up to the times.”

The news staff plied him with more questions about being among the early settlers of Bartow County, then known as Cass. In 1836, Abernathy’s father moved his family from Lincoln County, North Carolina, about three hundred miles of rough terrain, “never crossing a railroad track and forded nearly all the rivers as we found only two or three bridges over streams on the whole trip.”

Abernathy, a Primitive Baptist preacher, explained that the “Indians had just gone, and we could see their bark shanties they had left in the woods. There were only pig trails over most of the territory around here, and human habitations were far apart.”

The inquisitors continued to ask him questions, “Living near them, you knew the old Cooper Works on their better days[?]” Reverend Abernathy answered by detailing how people would come and buy iron and cookware before the Civil War. During the war, the Confederate government contracted for cannons and cannonballs. He reflected on the appearance and how the weapons were “turned loose on the Yankees to their great sorrow, I reckon.”

Abernathy, knowing he could talk away the day about a place he once knew, returned his corded wallet to his pocket and went out the door but looked back and said, “Send me up some writing material, and I will tell you more stories from the Macedonia settlement where lots of Abernathys live.” It was 1904.

The Cartersville News followed up with Elder Bard Abernathy six years later to report about his ten-month confinement from a fall and hip displacement. The News reported on his temperament: “No picture of pious resignation we have ever seen has equaled that which Mr. Abernathy displayed as he lay on his bed recently and talked so calmly and cheerfully to those around, never murmuring because of the confinement and suffering he had to endure, merely saying that those possessing good health should appreciate such a blessing.”36

The newspaper called him one of the most “interesting figures in Bartow County’s history. When he came to the area as a 9-year-old boy, the Western & Atlanta was under construction; he even helped lay the track.”37 He bought forty acres and lived in the community for seventy-two years before his death in 1914.

Elder Bard Larkin Abernathy was part of the Abernathyville community and is now buried in the Old Macedonia Cemetery There were many Abernathys, but there were also markers with the prominent names of Summey, Atkinson, Keever, McGhee, Blackburn, Cox, Dellinger, Howell, Tidwell and many others. The community nicknamed “Abernathyville” now resides beneath the murky green waters of Lake Allatoona

Abernathyville was lost to history before it was lost to the lake. Joe Head and the Etowah Valley Historical Society maintain an interactive map of communities at the Etowah Valley Historical Society map gallery.38 The map exposes areas lost to impoundment in the 1940s. One town that was unheard of until recent years was personal to Joe. He is an Abernathy.

The town was named for the large family, but it may be a nickname because the Macedonia community was built from the Stamp Creek District. The locals say that Abernathyville existed before the Macedonia Community. Once the Macedonia church was established, its neighbor, Abernathyville, surrendered its significance.

The cemetery was dedicated in the mid-1800s, and the first burial was Lintford Abernathy’s child. Lintford later donated the land to the church. The church was built following the cemetery, and the area became known as Macedonia. Inserts of the Macedonia school prove the town existed. On the banks of Allatoona Lake, this cemetery was saved from the flood waters, although it feels ominously close to the edge and some graves seem ready to slide in.

As early as the 1920s, the Georgia Power Company began plotting to dam up the Etowah River for hydroelectric power production, but the Great Depression ended those plans. In 1941, the Army Corps of Engineers began preparing the land for impoundment.

The land was purchased while workers dismantled the structures and homes in preparation for the coming waters. Macedonia assumed the graves were to be moved. Many cemeteries were condemned to rest on the bottom of the lake, including the famed industrialist Mark Anthony Cooper and family. However, in 1946, the Army Corps decided not to move the graves at Old Macedonia Cemetery. They built a new road. The old road to Macedonia (Abernathyville) was drowned.

Now the cemetery is cared for by the loving families, descendants of the pioneer town of Abernathyville and Macedonia. The remote area slopes down to the water’s edge, as if holding on as not to slip in and join the drowned town.

Driving down the desolate road that ends at Old Macedonia Cemetery, you wonder how many families once covered these red hills so close to the Etowah River. Arriving at dusk, the flickering of the lightning bugs is eerie. The light was marking the grave of a young man who died recently. His mother gave him a nightlight. The young death was likely tragic—as most are. The young soul, however, has a beautiful place to rest. He...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Land before the Lakes: The Difference between God-Made and Human-Made

- I. THE ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS LAKES

- II. THE GEORGIA POWER LAKES

- III. THE TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY LAKES

- Afterword. The Haunting Question, “What If ?”

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author