- 147 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Wicked Detriot

About this book

The Motor City boasts a long and sordid history of scoundrels, cheats and ne'er-do-wells. The wheeling and dealing prowess of founding father Antoine Cadillac is the stuff of legend. Fur trader and charlatan Joseph Campau grew so corrupt and rambunctious that he was eventually excommunicated by Detroit's beloved Father Gabriel Richard. The slovenly and eccentric Augustus Brevoort Woodward, well known as a judge but better known as a drunkard, renamed himself, reshaped the city streets and then named them after himself, creating a legion of enemies along the way. Local historian and creator of the Prohibition Detroit blog Mickey Lyons presents the stories of the colorful characters who shaped the city we know today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Wicked Detriot by Mickey Lyons in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

ANTOINE CADILLAC

Detroit’s Founding Scoundrel

Motor City. City of Champions. Motown. Paris of the Midwest. Murder City. Arsenal of Democracy. A city as grand as Detroit in its heyday, with its storied three-hundred-year history, must certainly have an equally epic story of origin, with the dashing Antoine Laumet de la Mothe, Sieur de Cadillac, as its heroic founder. Braving the wilds of winter and the perils of war, the great Cadillac, noble son of Burgundy, planted the flag of France on the banks of a narrow strait between two lakes on July 24, 1701. For years after, Cadillac guided the burgeoning colony with a firm but benevolent hand and defended its citizens against privation and predation by Jesuits, Iroquois and greedy voyageurs.

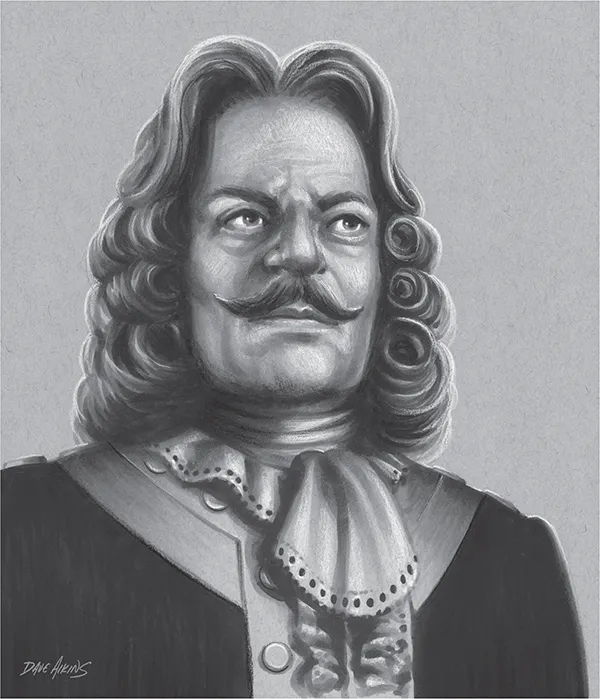

At least, that’s the PR version of Detroit’s founder. As it turns out, though, almost nothing we know of the city’s founder is true—even down to his very name and origin. Antoine Laumet was born on March 5, 1658, in St. Nicolas-de-la-Grave, a provincial town in southern France, halfway between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. Situated at the confluence of the Tarn and Garonne Rivers, the sleepy little hamlet offered very little in the way of grandeur—so Antoine Laumet decided to make some up. Antoine’s father, he later declared, was Jean de la Mothe, Sieur de Cadillac, Launay et Le Moutet, counselor to the parliament in Toulouse—his mother, Jeanne de Malenfant. In fact, his father was a simple small-town clerk-bailiff, and Antoine grew up in a middle-class home. So far as his later letters indicate, he received a decent education, with Latin and military history being among the subjects he studied.

As Antoine Laumet, he entered the military—probably. It has been suggested that he forged or borrowed the military record of an older brother. Regardless, by the time he set sail for the New World in 1683, the young man had dubbed himself Antoine de la Mothe, Sieur (Squire) de Cadillac. His family crest and noble name were likely borrowed from a neighbor in southern France, Baron Sylvester of Esparbes de Lussan, lord of Lamothe-Bardigues. Landing in Port Royal, a small peninsula in present-day Nova Scotia just across the Bay of Fundy from Mount Desert Island, Cadillac (as we will call him henceforth, for the sake of convenience) soon fell into the company and employ of Francois Guyon, a privateer plying the seas all along the East Coast, from Maine to the Carolinas. The young Cadillac ingratiated himself with his employer, and on June 25, 1687, he married Guyon’s niece, seventeen-year-old Marie-Therese Guyon.

Just two days after his marriage, Cadillac, then twenty-nine, applied for land grants from the French Crown and, no doubt thanks to his legendary arts of persuasion, received the gift of land in what is now northern Nova Scotia at Port Royal. Soon after, Cadillac wheedled his way aboard an excursion on the battleship Embuscade (Ambush) to explore and map the coast, noting English forts and strategic holdings. Gale winds and unfavorable seas, though, forced the ship to divert and make for France, where Cadillac immediately took advantage of the opportunity to ingratiate himself at court. There he convinced various ministers and hangers-on that he was intimately familiar with the British American coast and was promptly granted a lieutenancy in the naval forces.

Back on the coasts of North America, his young wife, Marie-Therese, was not so lucky. She had endured an attack on the Lamothe estates in Acadia and attempted to flee to France. Unfortunately, her ship was attacked by a British privateer outside of Boston, and the bulk of the Cadillac fortune, such as it was to this point, was lost.

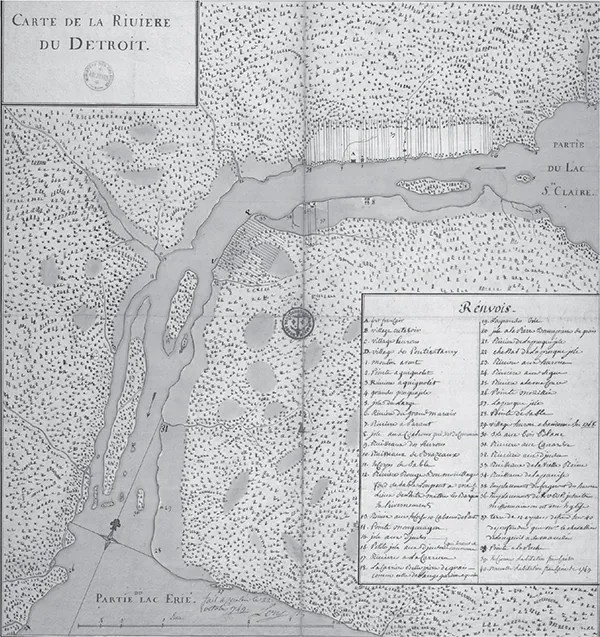

Once again nearly penniless and landless, Cadillac sprang into action. From 1691 to 1693, he busied himself with producing a map of the North American coast; it is unclear exactly how much of that coastline he personally surveyed and how much he simply manufactured from his vivid imagination. If contemporary maps are any indication, it mattered little. He presented them at court and was duly recognized as a master of military mapmaking; on his return to Quebec, Cadillac moved quickly through the ranks, collecting money and promotions as he went. In 1694, his ally Governor Frontenac promoted him to commander of all French forts in the northern territories, including its most strategic possession, Fort Michilimackinac. Demonstrating a pattern that would become all too common, though, Cadillac tarried at Quebec and Montreal for several months, then set out on a leisurely expedition to study his new domain.

Artist’s rendering of Antoine Cadillac, based on descriptions by his contemporaries. By David Aikens, author’s collection.

Another common Cadillac trademark was his remarkable ability to turn a profit, despite the strictures imposed on government agents in charge of trade in New France. Although rumors of his misconduct had begun circulating by the time he sailed for France to hand over his maps of the East Coast, he’d managed to reassure his patron, Count Pontchartrain, sufficiently that Pontchartrain’s ally Frontenac continued to support Cadillac’s swift promotions in the New World. By 1696, however, the allegations had become more heated. Cadillac’s rancorous relationship with the Jesuit priests stationed at Michilimackinac prompted a flurry of angry letters to the provincial governors.

Map of Detroit River, 1749. Library and Archives of Canada.

Simply put, Cadillac’s beef with the Jesuits can be boiled down to two factors: money and booze. Since the earliest days of French exploration in the Great Lakes, the court—convinced by the Jesuit missionaries who had been there since the 1630s—strictly limited the amount of brandy that could be traded to individuals or tribes in the Great Lakes. Constitutionally unaccustomed to the potency of the brandy and rum now available through trade, the Ottawa, Miami, Potawatomi and other tribes that traded with the French soon came to prefer the wet stuff as payment for the beaver pelts and deerskins they brought to the fort. Aside from the obvious effects brought by drunkenness, brandy proved a portable, consistent and stable currency in the backwoods and was traded among the tribes and the coureurs de bois with far more frequency than was reported.

Cadillac was more than happy to aid in the circulation of brandy throughout the region, regardless of decrees and quotas imposed by Montreal. It certainly helped Cadillac that, with demand and a limit to the official supply, he could charge up to twenty-five French pounds for a pot of brandy that would fetch only three pounds in Montreal.

The Jesuits, however, knew firsthand the liquor trade’s detrimental effect on the social and spiritual constitution of the First Nations tribes. Complaining that the tribesmen who came to the fort to trade were neglecting to purchase food, tools and other necessities to prepare for the harsh winters in favor of accepting only brandy as payment, the Jesuits began a series of strident letters to their superiors in the order begging for sanctions against Cadillac’s excessive trade. Another concern, they warned, was that the French could not compete with the lower prices and greater abundancy of liquor offered by the English trading in the area at the time. With tensions in the area between the Iroquois to the east and the Ottawa, Miami and Huron’s shifting alliances in the north and west, a catastrophic uprising was never far off.

At first, Cadillac, ever loquacious in his frequent letters to Quebec and Paris, brushed off the Jesuit’s complaints. On getting along with the Jesuits, he said, “I have found only three ways of succeeding in that. The first is to let them do as they like; the second, to do everything they wish; the third, to say nothing about what they do.”1 Despite this affable chaffing, though, Cadillac’s demands on the priests at his missions were intense. Claiming that the Jesuits “prefer certain hucksters, who have no weight with our allies” the Native American tribes, Cadillac essentially circumvented the Jesuits’ demands and those of the government by using government boats and soldiers to smuggle his contraband all over the northwestern area. In fact, within three years of his penniless arrival at Michilimackinac, Cadillac had sent 27,600 livres to France for safekeeping. Considering that the average late seventeenth-century settler in New France made an annual income of 75 livres, Cadillac’s scheme was highly profitable. By the time he reached Detroit, he had perfected this model.2

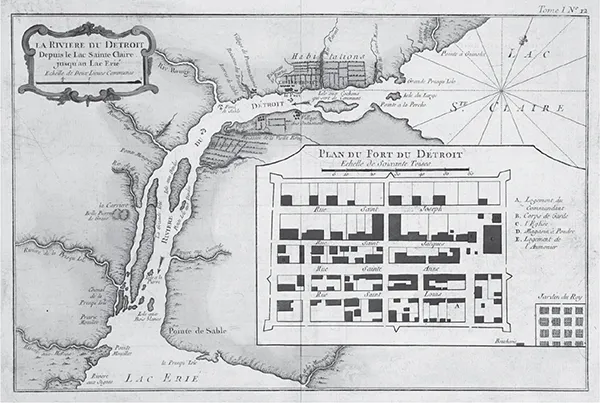

Fort de Detroit, 1749. Library and Archives of Canada.

His unorthodox methods did not go unnoticed. In 1796, while Cadillac was stationed at Michilimackinac, his wife, Marie-Therese, oversaw the departure of two boats from Montreal filled with trade goods destined for the fort, valued at 3,000 pounds. The two men in charge of the shipment, Louis Durand and Joseph Moreau, were authorized to bring a small amount of gunpowder and brandy for trade along the journey. In addition to the declared goods, Marie-Therese loaded the boats with as much contraband as they could carry for her husband to privately sell. Tucked discreetly among the official and not-so-official goods were a few items here and there that Durand and Moreau added for their own profit.

Before the boats departed Montreal, however, they were inspected by the fort’s commissary, and the illegal goods were discovered. The contraband was seized and catalogued, and Durand and Moreau were ordered to sign promissory notes for the value of the goods. Durand and Moreau were then permitted to continue on to Michilimackinac, where Cadillac promptly seized the goods as well as the promissory notes. He tossed the pair into jail, despite the fact that they had merely been following his private orders, and took advantage of their imprisonment to sack their home and small storehouse, taking every last item—including bills of credit the two had amassed totaling 3,100 pounds, to which Cadillac then signed his own name. He had Durand arrested again not long after for killing a dog belonging to one of the Ottawa people staying at the fort. Moreau, meanwhile, had no choice but to scrounge up what he could and set out to trade what little he had in order to start repayment on the seized goods.

Durand and Moreau took their case to court in Quebec. Cadillac fought it bitterly and at length, even going so far as to insist that the case should be heard in France. When the intendant of New France, Jean Bochart de Champigny, ruled that this was an unfair expense on the beggared Durand and Moreau, the case remained in Canada. Nevertheless, the case dragged on for over six months due to Cadillac’s ever-present obfuscations and objections. Durand, utterly penniless by now, was forced to settle his suit and accept a tiny fraction of what was taken from him. Moreau persisted, but after his application for credit based on an initial ruling was denied by Cadillac’s ally Frontenac, he was left with little option. To add insult to injury, Moreau had taken work on a fishing boat in Quebec in order to sustain himself; Frontenac had him arrested at the docks as he was preparing to set off, charging him with attempting to travel without government permission. Eventually, Moreau too settled for far less than was owed to him: Champigny ordered Cadillac to pay Moreau 3,400 pounds. Cadillac drew out the case even longer, dallying about finishing the paperwork, until Moreau settled for half of that amount. To top off his stinginess, Cadillac paid the fine in local (rather than continental French) currency, which meant that Moreau received only 400 pounds in the end, a little more than 10 percent of the original settlement.3

Cadillac’s tenure at Michilimackinac continued in this vein. At every opportunity, he squeezed any penny he could from whoever he could, whether they were Jesuits, settlers, traders or tribe members. His technique of flattery and sheer bullheaded persistence in the face of opposition made him few friends in the colonies. And while it did gain him attention in the French Court, Cadillac’s reputation was never that of an honest, hardworking pioneer; rather, although he strong-armed and cheated his counterparts in the colonies, his patrons and supervisors in France often preferred to let him do what he wanted rather than have to deal with his insufferable letters and outrageous claims of victimhood. They were content to keep him in the New World and out of their hair.

May 1696 dealt Cadillac and his schemes a hefty blow, however. Faced with a massive surplus of beaver skins and a decrease in the demand for them in Europe, the king declared a moratorium on licenses to trade in beaver in the colonies. The outpost at Michilimackinac was ordered shut down, effective immediately. Cadillac, incensed at his loss of position—and, more importantly, his loss of income—raced off to France to argue his case. With the recommendation of his old ally Frontenac in hand, Cadillac was promoted to lieutenant commander on arrival in Paris.

Taking advantage of his connections and his time at court, Cadillac presented a scheme for a new outpost in the New World. At a narrow strait between two sweet-water lakes, he declared, sat the ideal spot to control trade and simultaneously defend the Northwest against the imminent threat of conquest by the English and their Iroquois allies. With his trademark hyperbole, Cadillac declared the site a veritable paradise, a pastoral Eden untouched by human hands. Despite the fact that it’s possible he had never visited the spot—and confirmed reports from Jesuits and voyageurs who had been visiting the area for decades that the climate and terrain were problematic—Cadillac described le détroit du Lac Érié as such:

The banks are so many vast meadows where the freshness of these beautiful streams keep the grass always green. These same meadows are fringed with long and broad avenues of fruit trees which have never felt the careful hand of the watchful gardener; and fruit trees, young and old, droop under the weight and multitude of their fruit, and bend their branches toward the fertile soil which has produced them.…Under these vast avenues you may see assembling in hundreds the shy stag and the timid hind with the bounding roebuck, to pick up eagerly the apples and plums with which the ground is paved.…The golden pheasant, the quail, the partridge, the woodcock, the teeming turtledove, swarm in the woods and cover the open country intersected and broken by groves of full-grown forest trees which form a charming prospect which of itself might sweeten the melancholy tedium of solitude.4

Among Cadillac’s other claims for the idyllic new site, he stated that a canal already existed between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario; that a profitable silk factory could be established without delay; that the colony could easily produce wines to rival the best in Burgundy; that the area boasted native citrus similar to oranges, but whose fruit was an immediate and effective cure for snakebite; and that thousands of Huron, Miami and Ottawa were ready to pull up stakes from their settlements at Mackinac and move to the southern locale.

Not everyone at court was convinced. Cadillac’s unfavorable reputation as both a commander and a trader made him plenty of enemies. After several treks back and forth across the Atlantic, though, Cadillac talked his way into a commission to establish a fort at Detroit. Several letters from the time indicate that Cadillac was granted permission simply to remove his objectionable presence from court.

A statue representing Cadillac’s landing on July 24, 1701, stands downtown near Hart Plaza. Photo by the author.

On June 5, 1701, Cadillac departed from Montreal with twenty-five birch bark canoes, stocked with tools and supplies, alongside one hundred men. Soldiers, voyageurs and Native American allies made up the group, which traveled via the northern lakes—up the St. Lawrence River to Lake Huron and then down through Lake St. Clair. They landed at what is now the foot of Shelby Street on the Detroit River on July 24, 1701, and immediately began setting up fortifications and a small church of wooden stakes propped vertically. Although Cadillac’s landing at Detroit is much celebrated now, at the time, there was little to distinguish the fort from any other small settlement in New France—and the fort would remain small and obscure for many decades.

At Detroit, Cadillac continued his practice of extortion and smuggling, many miles away from the watchful eyes of government overseers. His habits of exaggeration and braggadocio continued apace; he declared that over the first winter at Detroit, six thousand settlers were inhabiting the site. Historians agree that the number was likely a fraction of that. Before winter, an important treaty had been passed in Montreal between the French government and more than forty First Nations tribes; this allowed the settlement to go forward, although the peace at Detroit was a tenuous one.

Having barely established his colony, Cadillac left in 1702 for Quebec to continue his manipulations; he secured a complete trade monopoly on behalf of the Company of Merchants, then operating in the area. Calling the company “beggarly and chimerical,” Cadillac insisted that he was the only man qualified to conduct trade around the lower Great Lakes. He also requested that he be made governor of Detroit. Aside from the alleged scheming of the company, he declared that the Jesuits, including his great rival Father Vaillant at Michilimackinac, “have sworn to ruin me in one way or another,” but that “the fox sooner or later eats up the hen.” Despite the generous percentages granted to Cadillac from his monopoly on official trade, not to mention his massive income from his smuggling ac...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Antoine Cadillac: Detroit’s Founding Scoundrel

- 2. Joseph Campau: Excommunicant Extraordinaire

- 3. Augustus Woodward: Brilliant Incompetent

- 4. William Hull: Craven Commander

- 5. Daniel J. Campau Jr.: Merchant Prince of Horsemen

- 6. Billy Boushaw: The Foist of the Foist

- 7. William Cotter Maybury: Not All that Bad, Really

- 8. Paddy McGraw: Much Ado about a Brothel Keeper

- 9. Charles Bowles: A Shameful Chapter in Detroit’s History

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author