![]()

1

ALL IN THE FAMILY

(1870)

She was a strange figure with a shadowy past, condemned by the press as having a “depravity of human nature that is horrible beyond anything developed [in Detroit] for many years.” Detroit reporters dubbed her the “Colored Lucretia Borgia,” and her case was so shocking that the story spread from the midsized midwestern metropolis to the headlines of the nation’s largest newspapers.

No known photographs of Virginia Doyle exist, but the historical record has left some tantalizing clues. Census records describe her as “white,” her death record describes her as “black” and newspapers characterized her as “mulatto.” Born a slave in Virginia in 1833, she may have ridden the freedom train to station one—Detroit—along the western route of the Underground Railroad.

Once in Detroit, Doyle joined a growing enclave of former slaves who settled in the vicinity of Beaubien Street. Death seemed to follow her every step, and in 1870, she became the focus of a headline crime that both stunned and bewildered Detroiters. The case also taught the reading public to be wary of pudding and port wine served up by overly ambitious relatives.

Nineteen-year-old George Talliaferro began to wonder if some strange curse had descended on the house at 274 Beaubien near Mechanic, where he lived with his grandmother Catherine De Baptiste and his best friend, James E.D. Ellis. The hardy De Baptiste had an iron constitution that served her well in the harsh climate of Michigan, but in February, she suffered from the first in a sequence of sudden, violent illnesses.

Talliaferro had cause for concern. De Baptiste was the family matriarch and the only real mother he knew—a woman he called “Ma.” His birth mother and De Baptiste’s daughter, Virginia Doyle, lived in another part of the city. She kept her distance, rarely visiting unless she wanted something. At some point, De Baptiste and her daughter had a falling-out; there were whispers, but whenever the issue arose, De Baptiste dismissed it with a grunt and a wave of her hand. Then, suddenly and unexpectedly, Doyle showed up on De Baptiste’s stoop in mid-February. The first bout of Ma’s mysterious illness occurred a few days later.

It was a serious omen. Several people closely associated with Virginia Doyle had an unexpected visit from the angel of death.

Doyle came with baggage that included three husbands, two of whom died untimely and highly suspicious deaths.

A longtime friend of the family, James Ellis knew all about Virginia’s marital history. Her first husband—George’s father—died about fifteen years earlier. He suffered from sudden, acute stomach pain and died in bed amid whispers of “arsenic.”

History repeated itself when Virginia remarried a few years later. Her second husband died after a sequence of crippling stomach pains left him prostrate and weak. On his deathbed, he confided to Ellis that he suspected Virginia had poisoned his food and asked Ellis to order a postmortem.

The postmortem never took place, but Ellis witnessed something sinister that convinced him Virginia had something to do with her second husband’s demise. Just days after the suspicious death, Virginia hired a boy to shimmy under the crawl space beneath her house. Ellis watched as the boy emerged, carrying a packet of white, crystalline substance that Virginia promptly tossed into the stove.

Virginia went on to husband number three—a mechanic from New York named Doyle who boarded in Virginia’s house. When Doyle left for New York on February 15, he suggested Virginia go to stay with her mother on Beaubien. At least, that was the story Doyle told when she knocked on De Baptiste’s door.

Three days later, Catherine De Baptiste suffered a sudden bout of illness after Virginia served her a saucer of pudding. Just minutes before the near-fatal desert, Ellis had noticed Virginia dividing the pudding into sections and ladling the portion for De Baptiste into a saucer. De Baptiste immediately felt “awful strange.” A dull sense of nausea became knots in the stomach that quickly evolved into agonizing abdominal cramps.

Ellis called Dr. Edward Kane, who administered an emetic to purge the old woman’s stomach. After De Baptiste vomited up the “mush,” she began to feel better.

The next day, the pains returned after De Baptiste downed a baked apple served up by Virginia. Since Dr. Kane’s treatment during the previous incident seemed to work, Talliaferro raced to the nearest chemist and purchased castor oil to induce vomiting. When De Baptiste recovered, Ellis and Talliaferro told her they thought Virginia was trying to poison her. Incredulous, she demanded proof before she would ever believe such a thing.

Ellis vowed to stop Doyle. He put all of the food prepared for De Baptiste under lock and key and set a trap. He made a bottle of beef tea, marked the cork, set it on the dining room table and left the house for twenty minutes. He figured Doyle would jump at the opportunity to make another attempt on De Baptiste. Sure enough, when he returned, the mark on the cork indicated that someone had tampered with it.

Talliaferro and Ellis confronted Doyle, who predictably denied everything.

Doyle’s next opportunity came on February 23, when De Baptiste asked Talliaferro to buy her some port wine. Ma poured a large glass for herself but left it on the dining room table when she went upstairs to bed. Remembering the goblet, she sent George to fetch it for her.

Talliaferro found the glass sitting in the exact spot where De Baptiste said it would be, but he also noticed something strange: white flakes floating on the surface. He looked at Doyle, who was sitting at the table. “My grandmother didn’t want any sugar in this,” he said. Doyle shrugged. She turned her head as Talliaferro sipped the wine.

It didn’t taste sweeter or different than any other port wine he’d had, so he went ahead and served it to De Baptiste. Both he and his grandmother spent the night writhing with sharp stomach pains. When Talliaferro awoke the next morning, he found the half-filled wineglass sitting on the night table besides De Baptiste’s bed. White specks hovered at the bottom of the glass.

He took it downstairs to the kitchen and poured off the wine, leaving just a little fluid and the mysterious white sediment in the glass. He and Ellis were studying the sediment when Doyle came into the kitchen. Talliaferro pointed out the white stuff to Doyle and asked her how she thought it got there. “I don’t know,” she said, her voice filled with irritation. “I don’t know.”

In an act of stunning defiance, Doyle hoisted the glass and sipped the strange lees, swishing it around in her mouth. She stared at the boys for a few seconds, her cheeks bulging and eyes glistening, then ran outdoors and spit it out on the paving bricks.

When Talliaferro said he wanted to have the contents of the glass tested by a chemist, Doyle’s eyes widened for a moment, then narrowed as she smirked—an expression that seemed to say he was being paranoid. At this point, George Talliaferro later testified, he became convinced that he and Ellis had foiled an attempt to poison “Ma” De Baptiste.

Talliaferro took the glass up to De Baptiste, who remained in bed weak from a night of retching, and asked her to hide it some place where Doyle would not find it.

He knew Doyle would begin searching for the evidence that could convict her.

Once again, he correctly anticipated Doyle’s next move. After chopping some wood in the yard, Talliaferro came inside to warm up and found Doyle upstairs hunting for the glass on the pretense of making the beds. He gave the “smoking” glass to Ellis, who locked it in a bureau. For the next few days, they moved the goblet from hiding place to hiding place to keep Doyle from finding, and destroying, the sinister evidence it contained.

A few days later, Talliaferro tiptoed out of the house and took the glass to chemist Alfred F. Jennings. The chemist confirmed Talliaferro’s suspicions: the white powder residue at the bottom of the glass was the heavy metal poison arsenic. Jennings estimated that the wine glass contained as much as five grains—more than enough to do-in Ma De Baptiste.

The chemist’s findings put Virginia Doyle in a cell at Central Headquarters and in the headlines. A Free Press reporter described the accused poisoner: “She took the matter very coolly, wearing a countenance not at all anxious, and smilingly declaring her belief that she would get some one to bail her.”

As the trial approached, public fascination with the mysterious figure grew. The soft-spoken thirty-seven-year-old Virginia native with a light southern drawl captivated the reading public. In between shots of whiskey at the local saloon or over tea in the family parlor, Detroiters debated the case, and for the first time, many of them heard the word matricide. What, they wondered, would motivate a woman to poison her own mother?

Talliaferro supplied one possible answer to this question when he testified at the preliminary hearing. De Baptiste owned her house, which sat on a sizable piece of real estate. Upon De Baptiste’s death, Virginia Doyle would inherit the property.

The trial opened to a packed house on April 9, 1870.

Detroit’s sizable population of female crime aficionados and armchair detectives, whose thirst for melodrama was quenched by high-profile murder trials, flocked to the courthouse. These shows—the best plays in town—always attracted a large audience of women. When they overflowed the women’s section of the gallery and spilled out into other rows, they drew the ire of reporters who had to crane their necks to see over a line of gaudy hats.

Many of them had watched the trial of Rosa Schweisstahl a year earlier, and the inevitable comparisons emerged in hushed conversations from the courtroom gallery. Both Schweisstahl and Doyle chose arsenic to do their dirty work but for different reasons. Schweisstahl used poison to remove one lover and make room for another, whereas Doyle spiked her mother’s food to acquire her property.

Jennings testified about finding arsenic in the wine glass. “I analyzed the contents of the glass brought to me by the last witness and discovered them to be arsenic. Some portion of it was found up along the rim, therefore I judge that there had been a greater quantity in the glass than there was when it was brought me.”

The chemist explained how a heavy metal poison would interact with port wine.

So, Jennings concluded, the tiny white chips floating in De Baptiste’s wine glass had been put there just minutes earlier, when the glass was on the dining room table.

The prosecution’s star witness, James Ellis, took the stand after the morning break. The twenty-seven-year-old from Fredericksburg, Virginia, came to Detroit as a teenager sometime just before the Civil War began.

“Mrs. Doyle had mixed some wine and toast which made ma [De Baptiste] deathly sick from 8 to 9 o’clock that evening.” He described the poisoned goblet. “I poured the wine out of the glass that was nearly full into an empty one and found about half a teaspoonful of sediment in the former. That day the old lady was very sick.”

Ellis never heard Doyle say a cross word to Ma, but he did hear her say something sinister at about the same time she came to stay with her mother. “Last winter I heard her say that she had one more deed to accomplish and then she would be free. I told her that she had better be praying and get her soul converted,” Ellis told the spellbound jury.

In a bizarre twist, the Free Press reporter sent to cover the case, Charles B. Lewis, was called to the stand to collaborate Ellis’s story about the poisoned wine. Ellis, he explained, had told an identical story during an interview.

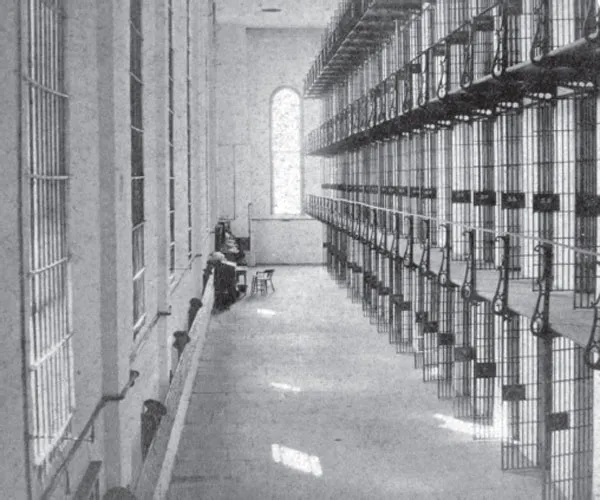

Sundowners stream through the barred windows and fall onto the floor of a cellblock inside the old Detroit House of Correction in this undated stere...