- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A look at the generals who were either born in the state or directly commanded its troops, including Braxton Bragg, Louis Addison Armistead, and others.

Confederate Generals of North Carolina provides a brief but compelling biography of each of the forty-six Confederate Generals who served from North Carolina during the Civil War. Each biography includes, in addition to the war service, a summary of a general's prewar and postwar careers. Author Joe Mobley (editor of the North Carolina Historical Review) also discusses the generals collectively: how many were killed or wounded, who attended West Point before the war, who achieved the highest levels of success both on and off the battlefield, and more.

"The Old North State could also boast some of the finest general officers in the Confederate army. Mobley provides a biographical sketch of each general's life with emphasis on his Confederate service record—as well as a wartime image of each." — Civil War News

Confederate Generals of North Carolina provides a brief but compelling biography of each of the forty-six Confederate Generals who served from North Carolina during the Civil War. Each biography includes, in addition to the war service, a summary of a general's prewar and postwar careers. Author Joe Mobley (editor of the North Carolina Historical Review) also discusses the generals collectively: how many were killed or wounded, who attended West Point before the war, who achieved the highest levels of success both on and off the battlefield, and more.

"The Old North State could also boast some of the finest general officers in the Confederate army. Mobley provides a biographical sketch of each general's life with emphasis on his Confederate service record—as well as a wartime image of each." — Civil War News

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Confederate Generals of North Carolina by Joe A Mobley,Joe A. Mobley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

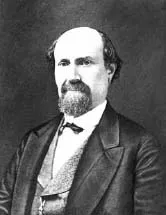

Rufus Barringer

1821–1895

Brigadier General

Rufus Barringer was born at Poplar Grove in Cabarrus County. His formal education began at Sugar Creek Academy in Mecklenburg County and continued at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, from which he graduated in 1842. He studied law first in Concord, the seat of Cabarrus County, with his eldest brother, Daniel Moreau Barringer, a U.S. congressman and minister to Spain. He then continued his law studies with the well-known jurist Richmond Mumford Pearson, who later became chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court.

Admitted to the bar, Barringer began practicing law in his home county and soon entered state politics as a Whig. Elected to the House of Commons in 1848, he played an important role in the incorporation of the North Carolina Railroad Company. He served in the state Senate in 1850–51 and then returned to the practice of law in Cabarrus County. In 1854, he married Eugenia Morrison, daughter of the Reverend Robert Hall Morrison, the first president of Davidson College. Two of Morrison’s other seven daughters also married Confederate generals. Isabella Sophia Morrison married D.H. Hill, and Mary Anna Morrison wed Thomas J. (Stonewall) Jackson.

Amid the bitter sectional discord tearing the nation apart in the 1850s, Barringer remained a staunch Unionist and opposed secession. During the presidential election of 1860, he served as an elector for John Bell, the candidate of the Constitutional Union Party. That party included many former Whigs, opposed secession, and called for the states to stand by the Union and the U.S. Constitution. But after Confederates fired on Fort Sumter in April 1861 and President Lincoln called for troops to suppress the rebellion, Barringer believed that the secession of his state was inevitable, and he began to prepare for war by raising a company of state troops for possible Confederate service. In late May, North Carolina seceded from the Union and joined the Confederate States of America.

Captain Barringer’s unit became Company F of the Ninth Regiment North Carolina State Troops (First Regiment North Carolina Cavalry) when it was organized at Camp Beauregard in Warren County in August 1861. Colonel Robert Ransom Jr. commanded the regiment, which transferred in October to Richmond and then to Manassas Junction in Virginia, as a component of General J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry. The regiment performed mainly scouting and guard duty until it was ordered back to North Carolina in March 1862 to meet a possible Federal attack in the eastern part of the state. A Federal expedition led by General Ambrose E. Burnside had recently captured Roanoke Island and New Bern and controlled a number of coastal counties, posing a threat to the interior of the state.

Barringer’s company returned to Virginia to aid in repulsing General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac advancing on Richmond along the peninsula between the York and James Rivers. In the Peninsula Campaign (March–July 1862), General Joseph E. Johnston originally commanded the Confederate force opposing McClellan. But after he was wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31, General Robert E. Lee took his place and reorganized the Confederate troops into the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee then launched a series of counterattacks known as the Seven Days Battles (June 25–July 1) to drive the Federals from the peninsula. That operation ended on July 1 with the Battle of Malvern Hill, where a Confederate attack on a strongly fortified Union position produced heavy casualties among Lee’s troops and failed to dislodge McClellan’s men, who nonetheless would soon evacuate eastern Virginia.

After Malvern Hill, Lee divided his cavalry into two brigades under the command of General Stuart. The Ninth Regiment (First Cavalry) was assigned to Stuart’s first brigade, commanded by General Wade Hampton of South Carolina. The regiment was left behind to guard Richmond during the Second Battle of Manassas (August 29–30, 1862), in which the Army of Northern Virginia defeated the U.S. Army of Virginia, commanded by General John Pope. Barringer’s company took part in an action at White Oak Swamp as McClellan’s troops retreated from the peninsula. The Ninth then rejoined the rest of Lee’s army on September 2 in time for its invasion of Maryland. Barringer’s Company F did not participate in the subsequent Battle of Sharpsburg (or Antietam) on September 17, but it did engage in skirmishes as the Confederate cavalry reconnoitered the Federals and screened Lee’s retreating column. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac had repulsed the Army of Northern Virginia and forced its withdrawal across the Potomac River.

During the Confederate victory at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December, Barringer’s regiment attacked the supply lines of Burnside, who had replaced McClellan in command of the Army of the Potomac. At Fredericksburg, Burnside ordered a disastrous charge against the heavily fortified Confederate position on Marye’s Heights. Because of his loss at Fredericksburg, he was replaced by General Joseph Hooker.

Lee defeated Hooker at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, but during the decisive Confederate victory, Hampton’s brigade was “south of the James River recruiting.” It then assembled with other units of the Army of Northern Virginia at Culpeper Court House for an anticipated campaign. At the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, Barringer’s regiment fought for most of the day and at one point routed the Tenth Regiment New York Cavalry, capturing its standard. During the fighting, Barringer received a severe wound to his face, but according to General Hampton, he “bore himself with marked coolness and good conduct.” A minié ball struck him in the right cheek, passing into his mouth and fracturing the superior maxilla and dislocating the upper teeth. Surgeons tended the wound the same day, but the injury remained permanent. Barringer was hospitalized in Salisbury, North Carolina, and remained on medical leave through August, missing the famed Battle of Gettysburg (July 1–3).

Upon returning to duty in Virginia, Barringer was promoted to major and transferred from Company F to the field and staff of the Ninth Regiment (First Cavalry). Other changes also took place in his brigade. Colonel Laurence S. Baker was elevated to brigadier general and command of what had been Hampton’s brigade. Hampton became the commander of one of the divisions of the newly organized cavalry corps of General Stuart, and when General Baker was given special duty because of wounds, Colonel James B. Gordon rose to command the brigade in Hampton’s new division.

In early October, Lee crossed the Rappahannock River and engaged the Army of the Potomac, commanded by General George G. Meade, in an action that came to be known as the Bristoe Campaign, which lasted until October 20, when Lee’s army withdrew across the Rappahannock. During the operation, Barringer and his fellow cavalrymen were engaged at Russell’s Ford, James City, Culpeper Court House, and Auburn Mills. At the latter site, on October 14, Colonel Thomas Ruffin, who had replaced Gordon as regimental commander, led a charge against infantry skirmishes threatening Confederate artillery. After Ruffin was wounded, Barringer quickly rallied the regiment and led another charge that forced the enemy to flee.

Although slightly wounded at Auburn Mills, Barringer remained on duty and, on October 19, led his regiment in a drastic charge at Buckland Mills, near Warrenton, Virginia. Frequently referred to as the Buckland Races, the attack completely routed a detachment of Union cavalry, who “fled in great confusion and were pursued for several miles with unrelenting fury.” Stuart sent Barringer a complimentary letter in which he referred to the North Carolinian’s command “as a pattern for others.” He soon received promotion to lieutenant colonel. William H. Cheek was promoted from lieutenant colonel to full colonel and given command of the regiment. In the ensuing Mine Run Campaign below the Rapidan River, Lee managed to force Meade’s withdrawal across the river. During the operation, the Ninth Regiment served as support for artillery and dismounted troops and engaged in some skirmishing. Both armies then went into winter quarters.

On January 1, 1864, Barringer left the Ninth Regiment to assume temporary command of the Fifty-ninth Regiment North Carolina Troops (Fourth Regiment North Carolina Cavalry). That unit traveled to eastern North Carolina for recruiting and picketing duty and in May was assigned to the District of Petersburg, Virginia, where it took part in operations in the Richmond vicinity.

In the meantime, General Ulysses S. Grant had become general in chief of the Union army, taken personal command of the Army of the Potomac, with Meade as a subordinate, and launched his Overland Campaign (May–June 1864). Grant’s objectives were to keep constant pressure on Lee’s army, force it back toward Richmond, and eventually effect its surrender. The Federals had heavy losses at the Battles of the Wilderness (May 5–6), Spotsylvania Court House (May 7–19), and Cold Harbor (June 1–3), but they ultimately forced the Army of Northern Virginia into trenches at Petersburg. At about the same time, the Army of Northern Virginia transferred its North Carolina cavalry brigade from Hampton’s division to the division of General William Henry Fitzhugh Lee, where it remained for the rest of the war. Before and during the Battle of the Wilderness, the brigade rendered important service in helping to check Grant’s advance, reporting hostile movements, protecting the infantry, and taking prisoners.

When General Philip H. Sheridan and twelve thousand Yankee horsemen launched a raid toward Richmond on May 9, Gordon’s brigade undertook to thwart their progress and, in the fighting that followed, lost soldiers and horses. With his other brigades, Stuart managed to get in front of and halt the Federal advance. But the dashing Confederate cavalry commander fell mortally wounded at Yellow Tavern. Gordon also received a wound on May 12 and soon died.

Barringer continued to lead the Fifty-ninth Regiment (Fourth Cavalry) until Gordon’s death. Then the North Carolinian returned to his old regiment, the Ninth (First Cavalry), and soon took command of the deceased Gordon’s Tar Heel brigade, with the date of rank of brigadier general from June 1. As part of the Army of Northern Virginia’s cavalry corps, newly commanded by Hampton since the death of Stuart, Barringer and his North Carolinians participated in numerous engagements leading up to and including the Battle of Cold Harbor.

With the main body of Lee’s army entrenched, Barringer’s brigade performed a number of raids and operations in the Petersburg area, including preventing Union troops from cutting or controlling the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad and the Richmond and Danville Railroad. At Reams’s Station on August 25, 1864, a combined attack of Confederate infantry, artillery, and cavalry finally drove the Federals from the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad. During that engagement, General William H.F. Lee was absent because of illness, and command of his division fell to Barringer. The cavalry attacked the Federals in their front, while the infantry and artillery assailed them in the rear. General Robert E. Lee subsequently remarked that “the brigade of Genl. Barringer bore a conspicuous part in the operations of the cavalry.”

After Reams’s Station, Barringer’s brigade participated in “eight severe actions” in the vicinity and “fought with varied success” in the famed Hampton’s Beefsteak Raid, in which the Confederate cavalry halted a stampede and secured a large herd of cattle for Lee’s starving troops. After the raid, Barringer’s men took part in a number of further actions to protect the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad before going into winter quarters near Belfield, where they rested, recruited, and performed picket duty.

At the Battle of Five Forks on March 31–April 1, 1865, Barringer’s troops attempted to halt U.S. cavalry led by General Philip H. Sheridan, but they were forced to move to Namozine Church, having heard that the Army of Northern Virginia had finally abandoned its trenches and was fleeing westward. At Namozine Church on April 3, Barringer’s soldiers took a position to await the attack of the Federal cavalry. In the ensuing battle, the brigade was virtually destroyed. “With less than eight hundred men in the line,” Barringer later wrote, “I had to receive the shock of over eight thousand,” along with an order “to fight to the last.” He was captured by a small party of U.S. scouts shortly after the battle. He therefore was not with the remnants of his brigade when they joined the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia as it fled westward. Lee finally surrendered that army to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9.

Barringer was transferred to City Point, Virginia, and placed under guard. While there, he met President Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln had gone to City Point to confer with General Grant, who had established his center of operations there. Accounts of the meeting between the Confederate general and the U.S. chief executive vary, but apparently a Federal officer at the site where a number of captured Confederate officers were housed in tents introduced Barringer to the president. Lincoln at first might have confused Barringer with his brother, Daniel Moreau Barringer, a congressman whom Lincoln claimed had sat with him before the war in the “Cherokee Strip,” an overflow of Whigs across the main aisle in the U.S. House of Representatives.

In the course of the conversation between Lincoln and Barringer, the general asked if he might be sent to the U.S. prison at Fort Delaware rather than the one at Johnson’s Island, Ohio. He had friends in nearby Philadelphia, he said, who might visit or otherwise be of service to him. Lincoln wrote a note, perhaps on the back of an official card, authorizing Barringer’s request and handed it to the general.

The Federals then transferred Barringer to Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C. While he was there, Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, and a week later, Barringer requested to see Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. At the subsequent meeting, the general presented Lincoln’s note to Stanton and requested to be moved to Fort Delaware. Stanton questioned Barringer at length, possibly in part to determine if he had any knowledge of the events leading to the assassination. The secretary of war then assigned Barringer to Fort Delaware. He was released from prison on July 25, arriving home on August 8.

Barringer moved to Charlotte and again took up his practice of law. He joined the Republican Party and supported Congressional Reconstruction, although he was not generally referred to as a “scalawag,” a term often applied by white southerners to native sons who joined the Republican Party and supported its Reconstruction policies. He served as a member of the state Constitutional Convention of 1875 and ran unsuccessfully as the Republican candidate for lieutenant governor in 1880. He retired from the bar in 1884 and devoted himself to writing about his wartime experiences. He supported temperance reform and industrial education and served as a trustee of the North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (now North Carolina State University) in Raleigh, chartered in 1887.

In the spring of 1894, Barringer’s health began to decline, and he sought recovery in northern sanitariums. But he soon accepted that he was not going to live long and returned home to Charlotte, where he died of stomach cancer on February 3, 1895. He was buried in Elmwood Cemetery in that city.

Barringer married three times. His first wife, Eugenia, died in 1858, and in 1861 he married Rosalie Chunn of Charlotte. After her death, he married Margaret Long of Orange County. He had three sons, one with each of his wives.

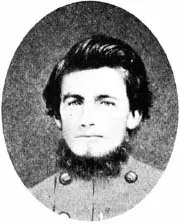

John Decatur Barry

1839–1867

Brigadier General (Temporary)

John Decatur Barry was born in Wilmington, North Carolina, and attended the University of North Carolina from 1856 to 1859. He resided as a banker in Wilmington until August 1861, when he enlisted as a private in Company I, known as the Wilmington Rifle Guards, of the Eighth Regiment North Carolina Volunteers, which transferred from state service to Confederate service around that time. In November, the regiment deployed for service in South Carolina, where its name changed to the Eighteenth Regiment North Carolina Troops.

When a large portion of coastal North Carolina and the town of New Bern fell to a Federal expedition led by General Ambrose E. Burnside in March 1862, the regiment relocated to Kinston, North Carolina, where it became part of the brigade commanded by General Lawrence O’Bryan Branch. On April 24, Barry was elected captain of Company I. At the same time, Robert H. Cowan replaced James D. Radcliffe as colonel of the regiment. In November 1862, Colonel Thomas J. Purdie replaced Cowan, and he led the regiment until his death at Chancellorsville, Virginia, in May 1863.

In early May 1862, Branch’s brigade was ordered to Virginia, where a Federal force under the command of General George B. McClellan was advancing toward Richmond from the east via the peninsula between the James and York Rivers. General Joseph E. Johnston commanded the Confederate army opposing McClellan in the Peninsula Campaign (March–July 1862). During that campaign, Barry saw his first major action at Hanover Court House on May 27. Three days later, General Johnston was wounded, and Robert E. Lee became commander of the Confederate troops in Virginia. Lee soon organized them into the Army of Northern Virginia and then launched a counterattack on McClellan known as the Seven Days Battles (June 25–July 1). During that fighting, Barry was wounded at the Battle of Frayser’s Farm (also called White Oak Swamp) on June 30. He remained absent from duty until probably sometime in October. On November 11, 1862, he was promoted to major and transferred to the regiment’s field and staff.

Barry and his troops went into action on the evening of the first day of the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, when Lee’s army clashed with the Army of the Potomac, then led by General Joseph Hooker. The Eighteenth sustained a large number of casualties, with thirty-four killed, ninety-nine wounded, and twenty-one missing. Colonel Purdie was killed and his second in command wounded. In fact, all thirteen field officers in the Eighteenth Regiment became casualties, except Barry. He then received a promotion to colonel and command of the regiment.

Although the Army of Northern Virginia drove Hooker’s force from the field on May 3 and won a major victory at Chancellorsville, it suffered a serious blow when General Thomas J. (Stonewall) Jackson was killed by fire from his own troops. Apparently, Barry himself ordered the volley that felled Jackson. In the late afternoon of May 2, Jackson, whose brilliant flanking of Hooker’s army helped carry the battle for the Confederates, rode out with his staff to make a reconnaissance of the enemy’s position. When Jackson and his staff returned through thick woods to their own lines, Barry’s regiment mistook them for Union soldiers and opened fire. Jackson was mortally wounded, and Barry took responsibility and blamed himself for ordering the volley that killed the famed general.

After his success at Chancellorsville, Lee marched his army into Pennsylvania, where in the first week of July he fought the Battle of Gettysburg against the Army of the Potomac, then commanded by General George G. Meade. During the vicious fighting, Barry led the Eighteenth North Carol...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- George Burgwyn Anderson

- Louis Addison Armistead

- Laurence Simmons Baker

- Rufus Barringer

- John Decatur Barry

- Braxton Bragg

- Lawrence O’Bryan Branch

- David Clark

- Thomas Lanier Clingman

- James Conner

- John Rogers Cooke

- William Ruffin Cox

- Junius Daniel

- Daniel Gould Fowle

- Richard Caswell Gatlin

- Jeremy Francis Gilmer

- Archibald Campbell Godwin

- James Byron Gordon

- Bryan Grimes

- Daniel Harvey Hill

- John Franklin Hoke

- Robert Frederick Hoke

- Theophilus Hunter Holmes

- Alfred Iverson Jr.

- Robert Daniel Johnston

- William Whedbee Kirkland

- James Henry Lane

- Collett Leventhorpe

- William Gaston Lewis

- William MacRae

- James Green Martin

- John Wesley McElroy

- William Dorsey Pender

- James Johnston Pettigrew

- Leonidas Polk

- Lucius Eugene Polk

- Gabriel James Rains

- Stephen Dodson Ramseur

- Matt Whitaker Ransom

- Robert Ransom Jr.

- William Paul Roberts

- Alfred Moore Scales

- Thomas Fentress Toon

- Robert Brank Vance

- William Henry Chase Whiting

- Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox

- Bibliography

- About the Author