- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Florida was the third Southern state to secede from the United States in 1860-61. With its small population of 140,000 and no manufacturing, few Confederate resources were allocated to protect the state. Some 15,000 Floridians served in the Union and Confederate armies (the highest population percentage of any southern state), but perhaps Florida's greatest contributions came from its production of salt (an essential need for preserving meat and manufacturing gunpowder), its large herds of cattle (which fed two southern armies), and its 1500 mile shoreline (which allowed smugglers to bring critical supplies from Europe and the Carribean). Florida in the Civil War: Blockaders will focus on the men and ships that fought this prolonged battle at sea, along the long and largely vacant coasts of the Sunshine State and on Florida soil. The information will be drawn from official sources, newspaper articles and private accounts. Approximately fifty (50) period photographs and drawings will be incorporated into the text.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Florida Civil War Blockades by Nick Wynne,Joe Crankshaw in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

In the Beginning

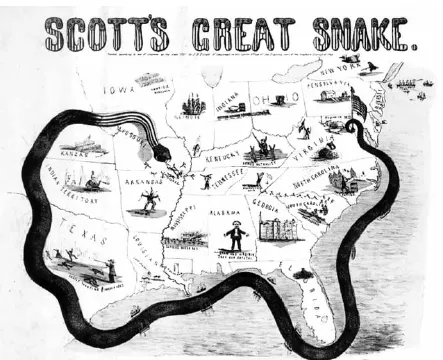

We rely greatly on the sure operation of a complete blockade of the Atlantic and Gulf ports soon to commence. In connection with such blockade we propose a powerful movement down the Mississippi to the ocean, with a cordon of posts at proper points, and the capture of Forts Jackson and Saint Philip; the object being to clear out and keep open this great line of communication in connection with the strict blockade of the seaboard, so as to envelop the insurgent States and bring them to terms with less bloodshed than by any other plan.

—Winfield Scott, May 3, 1861

With these words, written in a letter to Major General George B. McClellan, Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, the commanding general of the United States Army, proposed a key part of the Federal strategy for winning the Civil War. Although Scott, who had served as an American general for forty-seven years, would soon retire from active service and although his plan for enveloping and splitting the Confederacy would soon be modified by other generals, his basic proposal to isolate the Confederate states and to split the Confederacy remained largely intact. Labeled the Anaconda Plan by Unionist newspapers, Scott’s proposal was based on the idea that quick and decisive action by Federal land and naval forces would bring a rapid end to the rebellion. It was not to be, however, and the War Between the States lasted for four long years at the cost of almost two million casualties of all kinds.

Aged Winfield Scott, the top United States general in 1861, proposed his Anaconda Plan—as it was labeled in the press—to split the Confederacy and blockade its ports. Courtesy of the Wynne Collection.

Winfield Scott was an American hero from the Mexican-American War. When the Civil War started, Scott decided he was too old and infirm to lead the Union army. Courtesy of the Wynne Collection.

The essence of Scott’s plan was to implement a naval blockade of the three thousand miles of Confederate coastline from Virginia to Texas and prevent the importation of critical war supplies and to ensure that the Confederate government could not wield economic pressure on European nations—dependent on Southern cotton—to gain diplomatic recognition or military assistance. The plan was flawed from the beginning because the Union navy consisted of only a few ships, most of which were designed for open ocean sailing, not shallow coastal waters. Although the Federal government embarked on a crash program of building a “ninety-day” navy through the purchase of existing merchant ships and the construction of small coastal warships, progress was slow. Additionally, manning such ships required recruiting crews from merchant vessels and training raw recruits for sea duty. As a result, the blockade, when first adopted, was porous and easily circumvented by ships of the Confederate navy, as well as by privately owned Southern blockade runners. Even at war’s end in 1865, blockade runners and Confederate ships of war continued to be effective. For example, the CSS Shenandoah, under the command of James Iredell Waddell, continued to operate against Union commercial interests until late June 1865, two months after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House and Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. There were persistent rumors, although none can be substantiated, that Africans continued to be imported for use as slaves at the height of the Civil War.

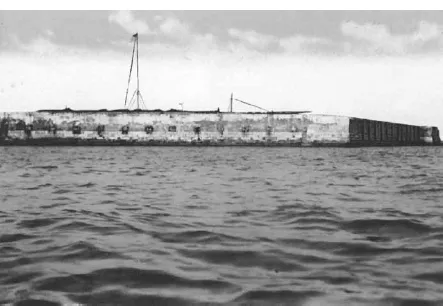

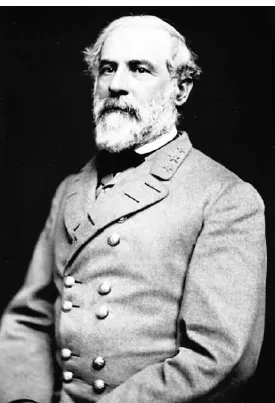

Confederate military and political leaders were no slouches, and they quickly directed state militias to take control of the series of coastal forts—Fort Clinch, Fort Pulaski and Fort Pickens—that provided protection for blockade runners at Fernandina, Savannah and Pensacola. Although Fort Clinch and Fort Pulaski were quickly brought under Southern control, Fort Pickens was occupied by Federal troops and remained in Union hands throughout the war. Some forts, like Fort Taylor in Key West and Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas, remained under the control of Union forces. Key West was simply too far down Florida’s landmass and difficult to access for Confederate forces to occupy and hold. So, too, was Fort Jefferson, which was even more difficult to capture and hold successfully. Both of these forts became important cogs in the blockade for Union ships. Lesser fortifications, like those at Apalachicola, passed in and out of Union and Confederate hands throughout the war. Robert E. Lee, who had been a secretary of a panel that conducted a survey of these forts prior to the outbreak of hostilities, recommended to Confederate president Jefferson Davis that these forts be held, if possible, but with little expenditure of men and equipment, and abandoned if Southern possession was directly challenged by a Federal invasion.

Fort Taylor became the stronghold of the Union army in Key West. The Federal army and navy quickly took control of the coastal forts on the Florida peninsula. Courtesy of the Ada E. Parrish Postcard Collection.

Robert E. Lee was offered command of the Union army by General Winfield Scott, but he refused to take sides against his native state of Virginia. He served the Confederacy initially by conducting an engineering survey of coastal fortifications in 1861. Courtesy of the Wynne Collection.

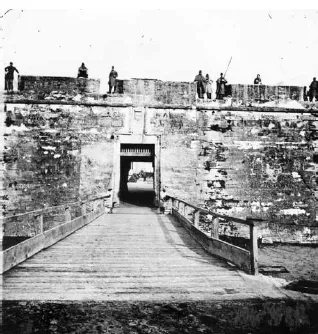

Florida, the third Southern state to secede, had few resources to dedicate to protecting coastal fortifications on its own. With barely 145,000 residents—half of whom were slaves—the Sunshine State was sparsely populated, and most of the 15,000 Floridians who served in the Confederate forces were sent to fight as part of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia or in the western theater of the war—Tennessee, Mississippi or Louisiana—under Braxton E. Bragg and Joseph E. Johnston. Quickly, Federal forces, already in possession of Key West and Pensacola, secured control of Fort Marion (Castillo de San Marcos) in St. Augustine, the port at Cedar Key with its railroad connection and the critically vital deepwater port at Jacksonville, which was occupied four times by the Union army. The early capture of Fort Clinch effectively blocked the direct shipment of war materiel and civilian supplies into Fernandina. The closing of these ports also prevented the out-shipment of beef, pork and salt to Rebel armies in more northern Confederate ports.

Unlike more developed Southern states, when war came in 1861, Florida had only one cross-state railroad, which had opened in 1860 and ran from Fernandina to Cedar Key. With the Union control of both ends of the road, it was quickly abandoned as a major transportation artery, and the rails from that road were ripped up and used to build shorter lines connecting Florida with larger, longer railroads in Georgia and Alabama. Cedar Key became a staging point for Union ships and minor incursions of Federal troops into the interior of the state. Seahorse Key, which effectively controlled entrance and exit from the harbor at Cedar Key, became a refugee camp for Floridians loyal to the Union cause and a prisoner of war camp for captured Confederates. Even after it was occupied by the Union forces, Cedar Key played only a minor role in the war.

Fort Marion in St. Augustine, formerly known as the Castillo de San Marcos, quickly fell to Florida state troops in 1861, although it was eventually abandoned to Union forces in 1861. Courtesy of the Florida State Photographic Archives.

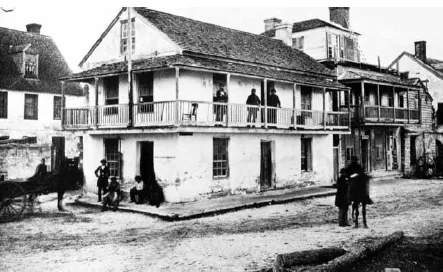

The city of St. Augustine was occupied by Federal troops through most of the war. It became a haven for runaway slaves and Florida Unionists. Courtesy of the Florida State Photographic Archives.

Still, Florida’s 1,500 miles of coastline presented a vexing problem to Federal military leaders, who envisioned hundreds of small blockade runners landing and unloading critically needed war materiel in the thousands of small inlets and bays along the coast. On the Atlantic side of the Sunshine State, the Indian River Lagoon, 155 miles long and protected against Union warships by barrier islands, presented a particularly onerous task to the Union navy to control. Mosquito Inlet, near present-day New Smyrna Beach, also offered numerous opportunities from small sloops and flat-bottomed steamships to land cargo unobserved since its shallow waters effectively blocked entrance by large seagoing vessels of the Union navy.

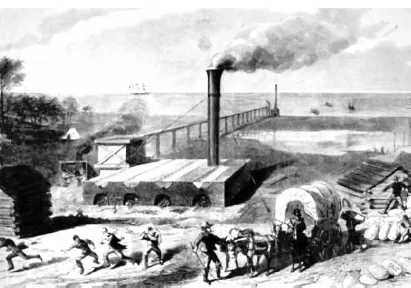

Added to the mission of the blockading ships was the job of finding, preventing and destroying thousands of small salt manufacturing operations, usually consisting of little more than a few copper kettles, fueled by driftwood and manned by a few men. The long coast and hundreds of broad beaches presented countless opportunities for Confederates to construct such distilleries overnight with little difficulty. Salt was such a valuable commodity—used in food preparation and the manufacture of gunpowder—that interior states sent special units to Florida’s coasts for the purpose of distilling seawater and harvesting the salt residue. After the Confederacy instituted a draft, salt workers were exempted from military service.

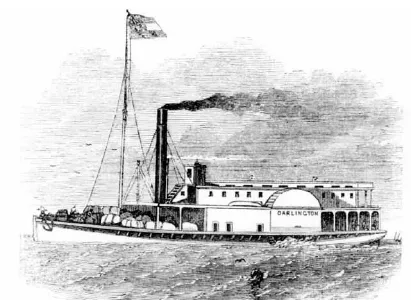

The Darlington, which was captured by Union naval vessels in Fernandina, was typical of the small steamers used by blockade runners to evade the larger ships of the Union navy. Its shallow draft allowed it to avoid the main channels of a harbor and escape capture by using small creeks and inlets. Courtesy of the Wynne Collection.

Saltworks were scattered along the coasts of Florida and produced tons of this much-needed preservative. Destroying saltworks became part of the routine duties of sailors on the vessels of the East Gulf Blockading Squadron. Harper’s Weekly, 1862. Courtesy of the Florida State Photographic Archives.

Florida’s long coastline also presented myriad opportunities for small sailing vessels and steamers to head out of Florida ports, loaded with cotton, cattle and tobacco, for Southern destinations. Cuba, the Bahamas and the ports of Mexico and Central America were popular places to carry the agricultural products of Florida, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas. Once offloaded, Southern exports could be sold and the money used to purchase military and civilian supplies, which were ferried back to the Confederacy. Once again, the Union navy faced the difficult challenge of stopping these operations, a task that it never completed successfully throughout the war.

Like the United States, the Confederate States had a navy, and like the Union, the Confederacy, which had no ships at all when the war began, purchased existing tonnage from commercial enterprises in Southern states or European companies or commissioned entirely new ships to be built at French and British shipyards. As the need for more ships grew, including ironclad riverine vessels, Confederate shipyards were constructed in several small cities. As the war dragged on, Confederate naval strategists began to envision a fleet of ironclads, heavily armored and steam powered, that could slip from small coastal harbors to wreak havoc with ships of the Union blockade and to offer protection for blockade runners.

Finally, the Union navy had to deal with the problems of establishing a supply line for its blockading ships, constructing new naval bases or modifying and expanding old ones; creating a waterborne medical system for dealing with diseases and wounds and housing; and feeding captured Confederate seamen. Training sufficient numbers of sailors to man the vessels of the blockade was a time-consuming but necessary task, because few of the merchant seamen of the day had experience in gunnery or were familiar with the rules of military service. Since one of the major tools used to recruit able-bodied seamen for Union ships was the opportunity to participate in the prize money from captured ships and cargoes, a workable system of naval courts to deal with confiscated ships and cargo had to be established. Existing federal and state courts in those areas under Union control had little experience with the international protocols that regulated the process.

The Federal navy consisted of a mere seventy-six vessels of all types when the blockade was ordered on April 19, 1861, and of these ships, only forty-two were in adequate repair to be used. Of the forty-two, thirty Federal ships were on station in foreign waters, which left twelve for use as blockaders. Of these twelve, only four ships, which carried a complement of 280 men and twenty-five guns, were pressed into immediate service.

Lincoln might easily proclaim a blockade of the Southern coasts, but it would exist primarily on paper for most of 1861 and early 1862. The lack of available ships meant that only a few harbors could be patrolled, but even then, Confederate shore batteries prevented the establishment of an effective blockade. Some ships that might have been added to the blockade fleet were ordered to work in support of Union army movements and to sail up navigable rivers as far as possible to destroy Confederate gun emplacements. In addition, some Union ships were periodically utilized to carry individuals from Confederate territories who, under a flag of truce, desired to join families or friends in Northern states. These demands further reduced the ability of the Federal navy to carry out its assigned responsibilities.

For the first several months, the Union navy proved to be ineffective in carrying out Lincoln’s order to blockade Southern ports and failed to stop movement into and out of these ports by Confederate or foreign ships. Gideon Welles, the Union secretary of the navy, reminded Flag Officer S.H. Stringham, the first commander of the Federal blockading force, that “a lawful maritime blockade requires the actual presence of an adequate force stationed at the entrance of the port sufficiently near to prevent communication.” Welles also reminded Stringham that “the only exception to this rule which requires the actual presence of an adequate force to constitute a lawful blockade arises out of the circumstance of the occasional temporary absence of the blockading squadron, produced by accident, as in the case of a storm, which does not suspend the legal operation of a blockade. The law considers an attempt to take advantage of such an accidental removal a fraudulent attempt to break the blockade.”

The small number of available Union ships negated widespread enforcement of the blockade and raised the specter of possible war with France and England over it. According to the Declaration of Paris, an 1856 treaty that defined the rights of neutrals and the requirements for a blockade, any recognized blockade had to be effective to be legal, and such was not the case for the United States. Although the United States was not a signatory to this international pact, Lincoln and Welles tried mightily to establish some semblance of effectiveness as a means of preventing European recognition of the Confederacy, but this was difficult to do convincingly.

The Confederate government recognized the need for diplomatic recognition very soon after the creation of the Confederate States. In February 1861, Robert Toombs, the Southern secretary of state, sent a three-man delegation to Europe to convince hesitant leaders there that recognition was deserved. To reinforce their request, Confederate authorities imposed a ban on the shipment of Southern cotton to European factories, an action that was designed to demonstrate the reliance of a large segment of the European economy on this staple. The delegation was composed of William Lowndes Yancey, Pierre Adolphe Rost and Ambrose Dudley Mann. Yancey, Rost and Mann were unlikely choices for such a mission, and the general speculation was t...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. In the Beginning

- 2. Finding a Way

- 3. Florida Goes Dark

- 4. The Blockaders: A Sailor’s Life

- 5. The Blockade Runners’ Friend: Yellow Fever

- 6. For Patriotism and Profit: Blockade Runners

- 7. Florida’s East Coast in the Blockade

- 8. Florida’s West Coast in the Blockade: Fort Myers to Bayport

- 9. The Blockade: From Cedar Keys to Pensacola

- 10. Contrabands and Kettles

- 11. Fish, Corn and Citrus

- 12. Cattle, Contrabands and Conflict

- 13. The Final Year: 1865

- 14. The End

- Additional Reading

- About the Authors