- 211 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Murder & Mayhem in Central Washington

About this book

Crime ran rampant at the turn of the twentieth century across Central Washington, from jail breaks, lethal bootleggers and assassinations in Kittitas County to shootouts and burglaries in Benton County. In Zillah, the Dymond Brothers Gang were known for stealing horses between prison stints. In Yakima, residents reeled in shock over the premeditated killing of a gambler, a riot and the discovery that a respected brewer had committed murder. Through it all, sheriffs like Jasper Day tried to keep the peace with mixed success. Author Ellen Allmendinger recounts the tales that once made this the roughest region of the Pacific Northwest.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Murder & Mayhem in Central Washington by Ellen Allmendinger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

KITTITAS COUNTY, WASHINGTON

THE ASSASSINATION OF DR. LYON (ROSLYN)

The community of Roslyn, Washington, began with the discovery of coal in 1883. Three years later, the area was platted and became a coal company town. The coal mines provided the main source of employment and also owned most of the city’s businesses. As a community, Roslyn’s successes were a direct result of the success of mining in the area. Likewise, the community’s failures were often centered on mining failures. Not unfamiliar with tragedy, Roslyn’s citizens experienced more than their share of tragic disasters in the late 1890s and early 1900s.

As a company town, the Northern Pacific Coal Company provided several services for its employees. Such services included the hiring of physicians to care for employees and their families. One of the first physicians hired to work for the company was Dr. John H. Lyon. Dr. Lyon experienced the devastating effects of coal mining accidents through the care of his patients. Such tragic effects on his patients’ lives may have also been the direct cause for the loss of his own life years later.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1852, John H. Lyon was about thirty-five years old when he arrived in Roslyn, Washington, as a doctor and single man around 1887. Little is known about his early life or his medical education prior to his arrival. Once in Roslyn, Dr. Lyon worked alongside Dr. Sloan as a Northern Pacific Coal Company physician.

Two years after his arrival in Roslyn, in September 1889, John married Jesse Mable Condit in Ellensburg, Washington. Born in 1864 in New Jersey, Jessie was twelve years younger than John when they married. It is unknown why Jessie had traveled across the country or when she arrived Kittitas County, although her arrival appears to have occurred within four years of their marriage.

John and Jessie lived in a home in Roslyn while John continued to work as a railroad company doctor. He earned one dollar per month for each miner he treated or prescribed drugs for. Practicing as a physician was not John’s only invested interest in Kittitas County. He was also very social and politically active and appeared to be living a happily married life. Sadly, he would soon endure a personal tragedy.

On April 16, 1892, three years they were married, the couple welcomed their first child, a baby daughter, into the world. Just weeks after their daughter’s birth, Jesse died on May 4, 1892. After her death, John had Jesse’s body transported back to New Jersey for burial in the Pleasantdale Cemetery. She was laid to rest at the cemetery where other members of her family had been interred. Now a widower with a baby daughter to care for, John remained in Roslyn practicing medicine. He would have little time to grieve his wife’s passing before disaster would strike the Roslyn community.

In 1892, Mine No. 1 of the Northern Pacific Coal Company caught on fire. Forty-five miners were killed in the fire, and many were also injured. More than twenty widows and eighty grieving children lost their husbands and fathers. The death toll, community grief and economic impact of the tragedy weighed heavily on the shoulders of the citizens of Roslyn, including Dr. Lyon.

Although life for many in Roslyn would never return to normal after the horrific fire, the damages from the fire were not significant enough to completely stop mining. As a result, the city’s main source of income was still mining. Sadly, this would lead to more tragedies.

Just months after the fire, a mining rail car accident occurred. As the mine’s night crews were leaving on the rail cars from the inside of the mine, the rail cars sped out of control down the hill. Most of the workers on board jumped from the car; however, two men did not. Joseph Erman, a single man, died immediately from the accident, while Charles Jones was seriously injured.

Dr. Lyon was placed in charge of treating Charles’s injuries—sadly, to no avail. Although it was decided that the engineer and wire rail worker were at fault for the accident, the finding did nothing to calm the anguish of Charles’s two brothers, J.J. and Thomas Jones, who were also miners in Roslyn.

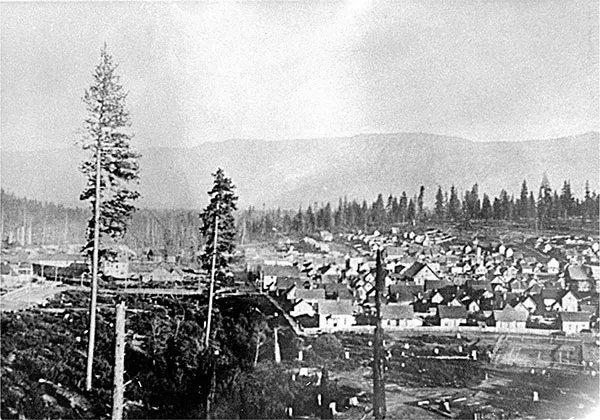

Overview of the city of Roslyn, Washington, in 1890. Courtesy of Yakima Memory, a joint project of the Yakima Valley Museum and Yakima Libraries.

Roslyn, Washington, in 1890. Courtesy of Yakima Memory, a joint project of the Yakima Valley Museum and Yakima Libraries.

Soon after Charles’s death, J.J. and Thomas Jones began making public threats against Dr. Lyon. Their threats were thought to have stemmed from what they perceived to be his failure to save their brother. Dr. Lyon, as well as others in Roslyn, was very aware of the brothers’ threats, although they were quickly forgotten when another historic event occurred.

In September 1892, Dr. Lyon entered the Ben Snipes & Company Bank. Upon entering, he quickly became involved as a witness to bank robbery. Although he survived the robbery, the ensuing trials would soon consume a great deal of both Dr. Lyon’s and the community’s time. As a witness, John became involved in identifying the bank robbers as well as attending the numerous trials held in Ellensburg, Washington.

None of the individuals identified by Dr. Lyon as participants in the bank robbery was found guilty, and their release led many in the community to question the verdict of innocence. Such unanswered questions continued in Kittitas County until four years later, when unknown criminals would murder Dr. Lyon.

On the evening of March 19, 1896, Dr. Lyon and Mr. Samuel Isaacs, a local merchant, were walking through Roslyn toward their homes. The two men eventually parted ways to continue their journeys. It would be the last time anyone would see John Lyon alive.

Just steps from his home, John was attacked from behind. During the attack, he received two blunt strikes to the base of his skull. It is believed that he dropped to the ground instantly and remained there until dying from a fractured skull. His body was not discovered until sometime after his death. No one is reported to have witnessed the attack, nor did anyone notice his body near his home. Reports claim that the attack and the delay in the discovery of his body were likely due to the evening being especially dark with rain clouds.

Once Dr. Lyon’s body was discovered, initial assumptions for the motive of his attack and murder were robbery—a theory that was quickly ruled out when his pocketbook and other personal belongings were discovered on his body. Along with these, other evidence relating to the crime was also found at the scene. A wooden table leg with hair and blood on it was discovered near Dr. Lyon’s body. Investigators were confident that the hair and blood belonged to Dr. Lyon. Investigators also found footsteps that led from Dr. Lyon’s body to the home of J.J. and Thomas Jones.

The footsteps combined with the earlier public threats made against Dr. Lyon were enough for the Roslyn City marshal to arrest the two Jones brothers. Other individuals involved in the investigation did not agree with the arrest. One such person was Detective Dan W. Simmons, who had formerly served as the Yakima County sheriff. Simmons was working on the murder case and felt that the evidence gathered was too circumstantial for a trial or conviction.

On March 25, six days after the murder of Dr. Lyon, the judge assigned to the case agreed with Detective Simmons. After a preliminary examination, the judge felt that the circumstantial evidence of the footsteps to the Jones brothers’ home was not enough to press charges or hold a trial. As a result, the brothers were released from jail.

After the release of the Jones brothers, the citizens of Roslyn applied public pressure to find the murderer by raising a $400 warrant for their arrest and conviction. The City of Roslyn’s leaders posted an additional $300 warrant at a city meeting the day afterward. Further rewards for the killer’s capture were also posted by Kittitas County, which added an additional $300, and the Washington State governor, who added another $500. In total, $1,500 worth of reward money was raised. Advertisements were also posted throughout the Northwest for the arrest and conviction of the killer of Dr. Lyon.

The large sum of money posted for the capture of Dr. Lyon’s killer, as well as the widespread advertising, ultimately proved to be futile. No known individual was ever arrested or tried for his murder, and the exact reason was never determined.

When Dr. John Lyon died, his daughter became an orphan, losing both of her parents one month shy of turning four years old. With no known relatives in Roslyn, Jessie was relocated to New Jersey, where she lived with an aunt and uncle on her mother’s side of the family.

THE VINSON MURDERS AND LYNCHING (ELLENSBURG)

Samuel Boyce Vinson was born in New York in 1841. He was in his early twenties and working as a laborer when he married his wife, Martha. Following their marriage, the couple had two children before they began their journey westward to Minnesota. In 1866, not long after their arrival in Princeton, Minnesota, a third child was born, a son named Charles. After his birth, the family remained living in Minnesota for almost two decades before once again moving west.

In the 1880s, the Vinson family arrived in Spokane, Washington, where they settled for a time. While there, Samuel supported his family by working as a U.S. marshal. A few years after relocating to Spokane, the Vinsons’ son Charles traveled farther west and ultimately moved around Western and Central Washington. It was during this time that Charles is reported to have started living a troublesome life that included multiple encounters with the law.

By the time Charles Vinson was in his early twenties, he was living under an alias by the name of Charles Collins and was thought to have committed various crimes throughout Western Washington. Those suspicions ultimately proved to be true when Charles’s lifestyle and real name eventually caught up with him.

In 1887, Charles was arrested in King County, Washington, for resisting an officer of the law. No known outcome of the arrest, or of any resulting trial, could be found in research. Although it appears that Charles managed to have avoided jail time for the incident, it wouldn’t be the last time he was arrested. The following summer, in July 1888, Charles was arrested for robbery. At his trial, he was found guilty as charged and was sentenced to two years in a Washington State Penitentiary. Sadly, he would not leave prison a changed man.

After serving his time for the robbery, Charles left Western Washington and relocated to the Kittitas County vicinity. By 1895, Charles had become a member of an outlaw gang in Central Washington. The gang was thought to have been responsible for various robberies throughout the region, although for a substantial amount of time none of the members was reported as being arrested or spending time behind bars—that is, until Charles helped law enforcement officials foil one of the gang’s robbery attempts.

In April 1895, the gang developed a plan to rob a passenger train near Cle Elum, Washington. The plan consisted of standing armed at the railroad tracks while wearing masks. Once the train stopped, they intended to rob the passengers of their money and valuables. Charles was reported as being included in the train robbery plan, although he is believed to have ratted out the rest of the gang’s plans.

After hearing Charles’s story, law enforcement investigated his claims. During the investigation, they went to the location Charles had described and found the gang members standing on the tracks armed and prepared to rob the train. The gang members were apprehended by law enforcement, arrested and taken to the Kittitas County Jail. Charles was also in jail at the time, although not for long.

Because Charles provided information about the robbery, he managed to escape any formal charges. After his release, he remained in the Ellensburg and Kittitas County vicinity, although many residents still considered him to be a criminal.

A few months afterward, Charles’s father, Samuel, who was no longer working as a U.S. marshal in Spokane, moved with his family to the Ellensburg vicinity. Like his son, Samuel had earned a reputation throughout the state, though for unsettled debts rather than crime. Various documents indicate that Samuel and his wife, Martha, spent time in court in both Western Washington and Yakima County for unpaid debts.

Both father and son were also reported as having severe drinking problems. The drinking issues caused the two, as well as other family members, a fair amount of trouble. Drinking would also be the cause of their eventual deaths.

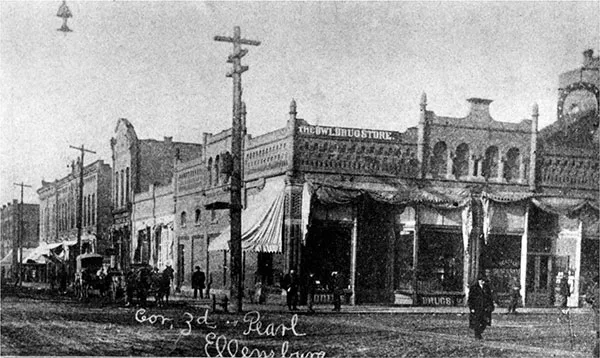

On the evening of Sunday, August 11, 1895, Samuel Vinson was already drunk when he followed Mr. John Buerglin into the Teutonia Saloon in Ellensburg, Washington. Located within the recently new constructed Cadwell-Lyons building at the corner of Third and Main Streets, the saloon was owned by partners Michael Kohlopp and Frank Ubbelacher.

Once the two men were in the Teutonia Saloon, Samuel attempted to convince John Buerglin to buy him a drink. Buerglin refused to purchase Samuel a drink, claiming that Samuel already owed him money. The two men became angry at each other and a fight ensued. At some point during the fight, Samuel stabbed John Buerglin in the chest.

At some point while Samuel was fighting John, Charles walked into the saloon. Seeing his father involved in a fight, he attempted to help. Michael Ubbelacher, one of the bar owners, noticed Charles entering the saloon and attempted to stop him from becoming involved in the fight by grabbing a club or pool stick. His attempts to prevent Charles from becoming involved failed quickly. Charles had entered the saloon with a revolver and immediately shot Ubbelacher in the chest from a distance of about four feet. Severely injured, Ubbelacher somehow managed to still try and hold Charles away from the fighting until he collapsed on the floor from his injury.

Eventually, law enforcement arrived at the saloon and managed to break up the fighting. While medical help was given to Ubbelacher, it was determined that the bullet had gone through his chest and lung. He died from the injury at eight o’clock that evening, just two hours later.

Looking west at the intersection of Third Avenue and Pearl Street after the fire of July 1889. The Cadwell-Lyons Building (at left) is shown at the corner of Third and Main Street. The building once housed the Teutonia Saloon, where the Vinsons’ bar fight led to their lynching. Photo by Otto W. Pautzke, “Corner of Third and Pearl Streets” (1898). Ellensburg History Photographs, no. 64, courtesy of the Local History Collection Photographs STS006001. Courtesy of the Ellensburg Public Library.

A wide-angle view of Pearl Street looking north to Eighth from the intersection of Third and Pearl Street. On the left side of the street is the Kleinberg, Geddis, Cadwell-Lyons (site of the Vinsons’ bar fight) and Lynch Buildings. Postcard titled “Pearl Street, Ellensburg, Wash.” (1905). Ellensburg History Photographs, no. 48, courtesy of the Ellensburg Public Library.

Meanwhile, John Buerglin, who had suffered a stab wound at the hands of Samuel, was able to walk to the office of Dr. Newland on his own accord. He was expected to survive; however, two days later, he succumbed to his injuries, living just long enough to ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I: Kittitas County, Washington

- Part II: Yakima County, Washington

- Part III: Benton County, Washington

- Bibliography

- About the Author