- 130 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The animal wealth of the western "wilderness" provided by talented "savages" encouraged French-Americans from Illinois, Canada and Louisiana to found a cosmopolitan center of international commerce that was a model of multicultural harmony. Historian J. Frederick Fausz offers a fresh interpretation of Saint Louis from 1764 to 1804, explaining how Pierre Lacl de, the early Chouteaus, Saint Ange de Bellerive and the Osage Indians established a "gateway" to an enlightened, alternative frontier of peace and prosperity before Lewis and Clark were even born. Historians, genealogists and general readers will appreciate the well-researched perspectives in this engaging story about a novel French West long ignored in American History.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Founding St. Louis by J. Frederick Fausz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Founding St. Louis:

ORIGINS

In all they wrought, the souls of these still live; Their deeds, their thoughts, each brave word bravely said, Live past the grave and master it, to give The living help and strength when life is fraught With sorest need of courage.16

THE PIONEER FROM THE PYRENEES

French he can speak, with such an air, As if the ways of courts he knew; And if he wore a sword, you’d say, It was the King who passed this way.

—Cyprien Despourrins

We cannot understand the founding of St. Louis without investigating the formative influences on its founder, Pierre de Laclède (1729–1778). All prior histories of St. Louis have neglected his first quarter century spent in the Pyrenees province of Béarn—more than half of his entire life—leaving a critical gap in our understanding of the man. The personal origins of those who change history are intertwined with their professional achievements in ways that are both evident and intangible. Genealogy, genetics and family relationships are critical aspects of heritage, of course, but distinctive landscapes and regional subcultures are also important for shaping individual experiences, developing personalities and determining destinies. It is particularly important to investigate the background of a native Frenchman who was legally a citizen of France but culturally a product of only one tiny part of that country.

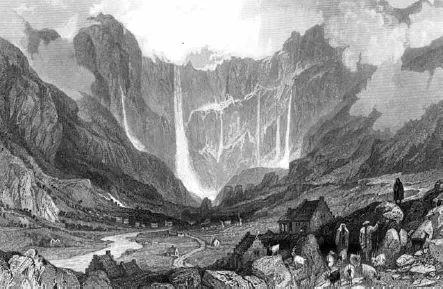

Laclède’s heritage and early life were firmly rooted in Le Béarn, a small and special world unto itself in southwestern France. That ancient province, now within the French Département of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques, is wedged between the Basque Country to the west and the Pyrenees Mountains on the east and south. Beyond that stoney southern boundary are Spain’s historic kingdoms of Aragon and Navarre; the former ruled Béarn until the ninth century, while the Béarnais “kings of Navarre” later lived in Pau, France. Located closer to Pamplona than Paris, Béarn was influenced by the Spanish and the Basques much earlier and for far longer than it was by the French. The Béarnais traded with Spain “since time immemorial,” and every year thousands of Béarnais, Basques and Spanish traveled to market towns through the Pyrenean passes that Laclède patrolled as a soldier in the 1750s. Merely exchanging commodities did little to alter varying values, cherished customs, distinctive dress or ancient languages—an important lesson for a future Indian trader.17

Spectacular Pyrenean waterfalls of Gavarnie with sixteen-hundred-foot drop. Drawing by Thomas Allom in France Illustrated (London and Paris, 1847). Author’s collection.

Béarn’s raging rivers, mineral springs, deep lakes and heavy rainfall fully justified its inclusion in Roman Aquitania, but political integration was another matter. The variegated topography of Béarn, including both broad, fertile plains and high, sterile mountains in a very small space, created a paradox between multicultural inclusion and subcultural exclusivity. For centuries, a vast variety of peoples—Romans, Visigoths, Franks, Vascons, Muslims, Normans, Spanish, Basques and even Calvinists from Geneva—entered Béarn. But like the pilgrims from around the world who still trek through the province to reach the famous shrine at Santiago de Compestela, Spain, the mere presence of foreigners did not transform local traditions. The choice to accept or reject cultural change remained with the native Béarnais. While the prohibitive highlands provided asylum from invaders, economic independence was sustained well below those snowy peaks by the rich soils and mild climate that nurtured vineyards, grain farms, huge flocks of sheep and pastures filled with Béarn’s famous cattle.18

The Béarnais, like the Basques, were a tribal “people apart,” speaking a unique language while resenting and resisting the imposition of authority by outsiders. Until the nineteenth century, Béarn gave more to France than France gave to Béarn, and the province was not even loosely incorporated into that nation until 1620. As late as 1788, the Béarnais claimed to live “in a country foreign to France” and still regarded Navarre and Béarn as “nations.” The French language was only a school subject until the end of World War II, and even today, a large percentage of the native Béarnais prefer to speak their distinctive dialect of the Gascon-Occitan language. Such pride and clannishness, according to Pierre de Marca’s 1640 Histoire du Béarn, were owed to the “natural fortifications” of the Pyrenees, giving the Béarnais an “elevated” opinion of themselves as “remarkably intelligent, and at the same time, simple in their habits and manners.” They cherished Béarn’s independence as a “republic of shepherds,” gently governed by local counts, princes and kings for half a millennium. The Béarnais expected their rulers to live among them as familiar celebrities, like clan chiefs, whose main concern was their welfare. The most beloved of their rulers, Henri III of Navarre (1553–1610), who would become the first Bourbon king of France as Henri IV, began life with garlic and the local Jurançon wine rubbed on his lips. His grandfather insisted that he be raised as a hardy, outdoor peasant lad rather than as a pampered prince. An expert swordsman and a womanizing playboy, that warrior king was a Calvinist who became a Catholic for his coronation as France’s monarch. His Edict of Nantes in 1598 reaffirmed Catholicism as the state religion but also granted freedom of worship to the Huguenots he once championed. “Good King” Henri’s concern for his subjects (desiring a “fowl in every pot”), his efforts for religious toleration, his preservation of Béarn’s forests and his impressive support of early French colonization in North America made him an excellent role model for a young Laclède. His study of local history surely made him aware that King Henri was descended from Saint Louis IX on his father’s side.19

Since the Béarnais did not subscribe to the gender bias of France’s Salic Law, their province also enjoyed a rich and rare heritage of strong and intelligent female rulers. King Henri’s mother was Jeanne d’Albret, queen of Navarre, who promoted Protestantism in her realm, and her mother was Queen Marguerite d’Angoulême de Navarre, sister of King François I of France. Marguerite was a patroness of Rabelais and an accomplished author herself, publishing the popular Heptaméron (1559), seventy-two short stories inspired by Boccaccio’s Decameron. Henri, “the Green Gallant,” married Margaret of Valois and then Marie de Medici, and his three daughters from that second marriage were Elizabeth, queen of Spain; Christine Marie, duchess of Savoy; and Henrietta Maria, queen of England.20

The attention that King Henri paid to finding excellent mates for his children was a dynastic necessity. But the value placed on family life and the perpetuation and reputation of one’s surname was shared by all landowning classes in Béarn, which included most of the peasants. “The single most important social organizing principle in the French Pyrenees is ‘the house,’ a complex value encompassing dwelling, property and family.” The House of Laclède, like the House of Bourbon, sought sustainability and continuity over the centuries through primogeniture—bequeathing all property, as well as “authority, reputation and status,” to a single, usually the eldest male, heir in each generation in order to preserve the maximum accumulation of property that symbolized social status. Younger males would receive a small settlement in cash or minor lands for renouncing their claims of inheritance, while women retained their material possessions in a marriage, as was the liberal French practice on both sides of the Atlantic. The so-called stem family tradition of primogeniture in the Pyrenees considered the local reputation of The House and its members to be the truest measure of “wealth,” and the mountain topography created the kin-based “neighborhoods” where a “sterling reputation” counted the most.21

Ice Age glaciers had carved four major valleys of north-flowing rivers (gaves) in Béarn, and since deep gorges and high peaks made overland east–west travel difficult and dangerous, local customs were preserved by upstream or downstream contacts with family and friends. The cultural conservatism of valued traditions that resulted from physical seclusion allowed Béarn to remain relatively unchanged in the eighteenth century. Without serious wars, famines or epidemics to disrupt the region in the 1700s, residents embraced the status quo, which they considered satisfying and already equitable. Even peasants were free farmers who owned their lands, and tenancy was virtually unknown. “Few provinces of Old France,” wrote a nineteenth-century Béarnais, “had such liberal institutions as the small independent state of Bearn.” A sociologist wrote recently that Béarn “society has always manifested an acute awareness of its values and a strong determination to defend the foundations of its economic and social order.” Only gradually, partially and always on their own terms did the Béarnais come to “share a common Atlantic orientation” of commerce and colonization through their proximity to the seaport cities of Bordeaux and Bayonne. There were always some residents who wanted to be involved with the epochal events that transformed the rest of Europe, including Pierre Laclède, who crossed more gaves than most Béarnais and would ultimately seek adventure in a much larger, watery world across the sea.22

A LIFE SHAPED BY ELEVATED EXPECTATIONS

Pierre de Laclède was born in the village of Bedous on November 22, 1729, to Magdeleine d’Espoey d’Arance (1697–1733), from a noble family, and Pierre de Laclède Sr. (1690–1776), a prominent, wealthy avocat (attorney). Their home was a multistoried mansion of whitewashed stone dating to the seventeenth century. While it lacked the size and splendor of Château Lassalle, owned by nearby nobles, the location of the Laclède house on the outer edge of Bedous and its castlelike tower identified the family as old, respectable and willing to defend the town’s two thousand residents. The Laclèdes lived along the small Gabarret River—the first river that Pierre crossed on his way to be baptized in Bedous’ Church of St. Michel. His godparents were from nearby villages: Jean Marie d’Arret was a merchant from Accous, and Suzanne de Lamarque was from Athas. At the baptismal font, Father Gabé probably pronounced the baby’s surname “Laclayed” in the Béarnais language, rather than the French “Lacled,” and certainly not the “Lacleed” that present-day St. Louisans prefer.23

The Gabarret River in which young Pierre played was a tributary of the legendary Gave d’Aspe, connecting Urdos on the Spanish border with Oloron (Oloron-Sainte-Marie since 1858), the largest local town. Bedous was within its Roman Catholic diocese, which is famous for its twelfth-century Romanesque cathedral. Oloron grew wealthy and influential in the medieval textile trade with Aragon due to its location at the confluence of the Aspe and Ossau Rivers. Even though the “green, bright and foaming” Aspe River was only about twenty-five yards wide, it was one of those “magnificent torrents” that contributed to “the charm of the Pyrenees, making the country…a scene of beauty and animation…[and] singular grandeur.” However, as Laclède learned as a child, the “uncontrolled majesty” of such streams could take an angry turn, creating a horror when summer thunderstorms swelled rushing waters from melting mountain snowcaps. Devastating floods did “terrible mischief” in Béarn, as rivers escaped their low and narrow banks to inundate defenseless towns.24

Maison de Laclède in Bedous, where Laclède was born. Photograph by Pier, circa 1960. Courtesy Missouri History Museum, St. Louis.

At the confluence of the Aspe and Gabarret Rivers near Laclède’s home, the landscape was rural and agricultural. Surrounded by forests, meadows and fields, Bedous was centrally located in the “garden of Béarn”—a region of foothills that were fifteen hundred feet above sea level but in sight of mountain peaks that were eight thousand feet higher. “The plain of Bedous” was “highly cultivated and very picturesque”—a beautiful “little Paradise,” as one visitor discovered. “I could hardly believe my eyes,” wrote Arthur Young, an English agricultural reformer in the late eighteenth century, when he observed the prosperity of even the smallest farms in Béarn. “Neatness, warmth, and comfort” described the bountiful fields, healthy livestock and tile-roofed stone houses he regularly encountered among the peasantry. Adding to the charm of that “happy valley” were several green, conical hills or mounds (called turons) that “constitute one of the most characteristic features of the scenery,” a microcosm of “the buttresses of lofty sugar-loaf mountains” farther south. Bedous was also surrounded by six other small villages, all located along the Gave d’Aspe. Most notable were Osse (present-day Osse-en-Aspe) and Accous. Well into the nineteenth century, Osse had a Protestant church and a thriving congregation, a rare reminder of the Calvinist enclaves that flourished in Béarn, La Rochelle and elsewhere in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Accous, located only a mile and a half directly south of Laclède’s home, was “highly cultivated and adorned with the cottages of the peasantry” but was most famous as the birthplace of the popular pastoral poet and swashbuckling swordsman Cyprien Despourrins (1698–1759), who wrote:

The Aspe and Ossau Valleys, showing Laclède’s Bedous and adjoining villages. Robert (Vaugondy), Partie Meridi du Gouvernement de Guienne…et Béarn, 1757. Author’s collection.

The riches of the world bring only care and pain,

And nobles great and grand, with many a rich domain,

Can scarcely half the pleasures, with all their art, secure,

That wait upon the shepherd, who lives content and poor.25

Despourrins attracted a new audience in the Romantic Age, especially among English gentlewomen, who fell in love with the Bedous area: “It is scarcely possible to imagine a region more fitted to…poetic feeling than this, or more calculated to give sublimity and power to the…human mind.” Despourrins’s theme of contentment amid poverty captured the imagination of Sarah Stickney Ellis, who in 1841 commended the Béarnais for “their obliging good nature and the simplicity which characterizes many of their habits”—especially their lack of “pretension: A peasant is a peasant, a shopkeeper a shopkeeper, a gentleman a gentleman…and men are not ashamed to appear what they really are.” To her, that represented “moral courage…in daring to be poor—in dressing and living according to their means, when these means are extremely limited.” Ellis believed that the “cheerfulness of the Béarnais is that of regularly animated industry, [for] each individual, having his wealth and his power within himself, and no human influence to conciliate or to fear, is able to gather in security and peace the full return of his unremitting activity.” She also linked that “almost uniform cheerfulness” to the “delightful climate” of the lower Pyrenees. “There is an effect produced by the clearness of the atmosphere, the brightness of the sunshine, and the elasticity of the air” that enhanced the “sensation of being alive.” It was “a perpetual enjoyment” that made “another day welcomed as another blessing.”26

English writers, who rarely complimented the French, found the Béarnais to be “clean, active, good-natured, and cheerful,” having the “general appearance of order, industry, and prosperity” that was “far superior to the inhabitants” of the higher Pyrenees to the east. Physically, the men of the Pyrenean foothills were “a noble looking race”—handsome, hardy and tall, often “above six feet in height, thin, agile, and admirably formed.” Visitors commended their white teeth; jet-black, shoulder-length hair; “vigorous complexions”; physical strength; and athletic ability. Shepherd boys were described as “the most beautiful specimens of human nature,” brimming with “glowing health and buoyant youth.” Outdoor physical activity contributed to the “industrious hardihood” of men who climbed rocks for business or pleasure. Shepherds practiced transhumance, ascending mountains with flocks of sheep to pasture them on elevated grazing meadows (estives) all summer long, while the gentry fished for trout and salmon in highland streams and hunted brown bears and wild goats (izards or chamois) amid the peaks. The young women of Béarn were considered “extremely handsome, too, with dark eyes and fine features,” and some were tall enough to be “majestic-looking.” Peasant women got their exercise sowing fields and tending crops while male shepherds were far from home. Entire villages of women, wearing “glitter...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- A Note on Terminology

- Introduction. A French Heritage Lost and Found

- Part I. Founding St. Louis: Origins

- Part II. Fashioning St. Louis: Operations

- Epilogue: Finding and “Fixing” St. Louis

- Notes

- About the Author