- 227 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lake George Shipwrecks and Sunken History

About this book

Discover lost history in the dark waters of Lake George. Lake George is bustling with boaters, swimmers, fishermen and many others, enjoying its scenic, quintessentially Adirondack shores. But the depths below hide a whole other world--one of shipwrecks and lost history. Entombed are remnants of Lake George's important naval heritage, such as the legendary Land Tortoise radeau, which sank in 1758. Other wrecks include the steam yacht Ellide and the first famed Minne-Ha-Ha. These waters hold secrets, too, like the explanation behind the 1926 disappearance of two hunters. After years of exploration across the lake's bottomlands, underwater archaeologist Joseph W. Zarzynski and archeological diver Bob Benway present the most intriguing discoveries among more than two hundred known shipwreck sites.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lake George Shipwrecks and Sunken History by Joseph W Zarzynski,Bob Benway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

NATIVE AMERICAN WATERCRAFT

NATIVE AMERICAN CANOES FROM LAKE GEORGE

For many centuries, long before Lake George became a popular resort destination, the thirty-two-mile-long waterway and the forestland around it were seasonal fishing waters and hunting grounds for Native Americans. The earliest Native American vessels at Lake George were dugout canoes, wooden watercraft fashioned from logs. After removing the log’s bark, the timber’s interior was hollowed out by a controlled burn, and then it was hand carved, using an adze or other tool. The log’s ends were often tapered to give it a more hydrodynamic design. The indigenous peoples at Lake George later used bark canoes that were considerably easier to maneuver in the water and were also lighter to pull up on shore or to portage.

Canoes were powered by one or more Native Americans, each canoeist with a single-bladed paddle. Because the paddlers faced in the direction they were going, unlike traditional European-style rowed watercraft, it gave the occupants an advantage in navigation.

The Lake George Historical Association (LGHA), a museum in the Old Courthouse Building in the town of Lake George, has a Native American dugout canoe on exhibit. The 15.5-foot-long watercraft dates to the fifteenth century. The LGHA’s dugout canoe was reportedly discovered in 1915, found by Edward H. Moon and Clayton N. Davis of Fort Edward, New York. The crude vessel was recovered from the mud of Dunham’s Bay Creek on the east side of Lake George. Several dugout canoes are also in Fort William Henry Museum’s collection in Lake George.

This 15.5-foot-long, fifteenth-century Native American dugout canoe is exhibited at the Lake George Historical Association. It was discovered in 1915, recovered from “the mud of Dunham’s Bay Creek on the east side of Lake George.” Courtesy of Bob Benway/Bateaux Below.

In the 1960s, some scuba divers reported seeing Native American bark canoes resting in Basin Bay on the west side of the lake. On September 3, 1983, a partially buried Native American bark canoe was observed in Lake George near Diamond Point by scuba divers Jack Sullivan, his son, John, and Joseph W. Zarzynski.

Bark canoes were built in a variety of sizes, from the one-man hunting and fishing canoe to canoes large enough to transport a war party or a ton of trade goods. Native American bark canoes were generally constructed of birch, elm or hickory bark that was reinforced by a light wooden frame. Its lightweight, relatively fast boat speed and load-carrying capacity impressed the early Europeans. However, bark canoes often required frequent repairs to fix tears and holes.

Finding a centuries-old Native American bark canoe is rather rare since their fragile forms are quite perishable, unlike the durable dugout canoe, whose form is exhibited in many museums around the region. Furthermore, it is difficult to preserve Native American bark canoes for museum exhibition since, as they age, the bark becomes brittle and, therefore, can easily be damaged.

Generally speaking, bark canoes of various sizes, differing materials and methods of construction were found within a single tribal area. Often when Native Americans moved into other areas, they were quick to borrow construction techniques and forms from neighboring tribal groups. Nevertheless, the distinctive feature of an American Indian canoe that generally identifies the tribe is the profile of the ends of the bark canoe.

Ironically, many lake residents and visitors today enjoy canoeing or kayaking on the Queen of American Lakes, using watercraft designs traced back to early Native Americans.

CHAPTER 2

FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR SHIPWRECKS

OPERATION BATEAUX: 1963–1964

Published June 4, 2004, Lake George Mirror

Over forty years ago, Terry Crandall, a scuba diver who worked for the Adirondack Museum, conducted two summers of archaeological fieldwork, mapping several dozen sunken bateaux, the twenty-five- to forty-foot-long French and Indian War–era vessels found on the bottomlands of Lake George. Thus, it was not surprising that on June 5, 2004, the New York State Divers Association honored Crandall as its Diver of the Year at the organization’s state convention held in Lake George.

Crandall, a former teacher and school administrator, started exploring the deep in the 1950s when he dived Canadarago Lake in Richfield Springs, New York, using Miller Dunn hard hat equipment. In the early 1960s, he taught scuba classes in Johnston, Gloversville, Oneonta, Herkimer and Cooperstown, New York. From 1964 to 1965, Crandall was president of the New York State Divers Association when the group’s annual convention those two years was held at Dunham’s Bay Lodge at Lake George.

In 1963, Crandall was hired by the Adirondack Museum and was designated as a “diver archaeologist” by the Blue Mountain Lake museum’s Dr. Robert Bruce Inverarity. Crandall’s task was to explore the depths of Lake George, searching for shipwrecks of the Sunken Fleet of 1758, 260 bateaux and several other classes of warships deliberately sunk by the British to prevent them from falling into the hands of their enemy, the French. The 1963–1964 project was conducted under a permit granted by the New York State Education Department, and the endeavor was appropriately dubbed “Operation Bateaux.”

Terry Crandall was the Adirondack Museum’s archaeological diver during Operation Bateaux from 1963 to 1964. Courtesy of Terry Crandall.

Although Operation Bateaux was primarily a one-person dive operation, Crandall often teamed up with other local divers who volunteered their time and expertise. Most notable of these were Lee Couchman, Charlie Dennis, Gene Parker and Jack Sullivan. According to Crandall, search dives were conducted along “a bottom contour depth of from fifteen- to twenty-five-foot average” following a zigzag pattern “forty-five degrees east and west of [a lubber line].” Warren County sheriff Robert Lilly and the Lake George Park Commission provided boat support to and from the dive sites. After completing these scuba forays, Crandall recorded his search area and finds French and Indian War Shipwrecks on the Lake George Power Squadron charts “using a gridded overlay…[so that] a day’s search [zone] could be described with a few six digit codes.” Crandall’s grid system permitted him to accurately record his shipwreck discovery locations onto lake charts. The two-year effort resulted in a site map of more than thirty colonial bateau wrecks being located and mapped.

When Crandall found a sunken bateau whose structural integrity looked good, he would hand-fan the mud overburden to expose the pine planks and oak frames for photographic purposes. In some cases, artifacts such as “clay pipe fragments, musket and bird shot of all sizes, even…cuff links [that] were found lying on [bateau] floor boards” were removed. Those artifacts and his numerous field reports were then transported back to the Adirondack Museum.

Crandall was innovative, too. He collected measurements of bateaux using “a metal retractable ruler on a piece of clear plexiglass panel.” The plexiglass “enabled site drawings to be made looking through the panel to approximate angles as they existed.”

Crandall discovered that many sunken bateaux had amazing states of preservation, as some “showed definite signs of caked mud tracking from the shoes of the ‘troops,’ which could be removed quite intact from the bottom boards themselves.”

Unfortunately, bureaucratic problems and the departure of Dr. Inverarity from the Adirondack Museum in the mid-1960s contributed to the cessation of Operation Bateaux after only two years’ duration. However, in 1988, Crandall became a member of the archaeological organization Bateaux Below, and he now serves as one of the not-for-profit corporation’s trustees.

The legacy of Crandall’s 1963–1964 Operation Bateaux is very much evident today. His pioneering archaeological recording conducted over four decades ago established baseline data that is frequently utilized today by Bateaux Below in its study of the lake’s Sunken Fleet of 1758.

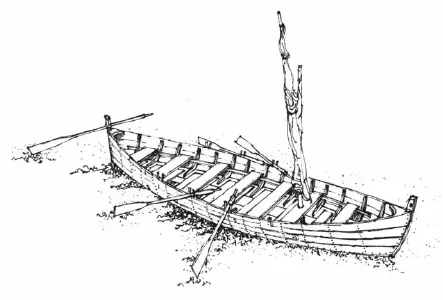

Terry Crandall’s drawing of a typical 1758 British bateau, based on the archaeological record from Lake George. Courtesy of Terry Crandall.

MISSING, FOUR SHIPWRECKS OF THE SUNKEN FLEET OF 1758

Published July 23, 2004, Lake George Mirror

In the autumn of 1758, British forces at Lake George completed a deliberate sinking of its battle craft to prevent them from falling into the hands of the French and their Native American allies. British and provincial soldiers sank 2 floating gun batteries called radeaux, the sloop Earl of Halifax, some row galleys and whaleboats and 260 bateaux. This group, known as the Sunken Fleet of 1758, was submerged because Fort William Henry had been destroyed, and, thus, there was no British garrison to protect their flotilla over the winter. The plan was to retrieve these submerged boats the following year, when the British returned to Lake George. Two centuries later, in 1963–1964, many bateaux of the sunken fleet were investigated by the Adirondack Museum. However, more recently underwater archaeologists with Bateaux Below have studied these French and Indian War–era vessels and are perplexed by their findings. Four bateau wrecks noted during the 1960s are missing!

The colonial bateau was the utilitarian vessel of inland waterways during the colonial period. Courtesy of Mark Peckham.

The bateau (spelled bateaux in the plural) was twenty-five to forty feet long, flat bottomed and pointed at the bow and stern. Fashioned from pine planks and oak frames, a bateau could be rowed, poled in shallow water or rigged with a crude mast and sail. An oar was latched to the stern for steerage.

Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Lake George Mirror newspaper reported that several bateaux were observed in the shallows of the waterway. Decades later, in 1960, two teenage scuba divers “discovered” several submerged bateaux lying near the head of the lake. In September 1960, several of these warships—probably three—were raised by the Adirondack Museum. They were conserved and today are in storage at the New York State Museum.

In 1963–1964, Terry Crandall, a diver hired by the Adirondack Museum, located more than thirty bateau wrecks in the lake’s southern basin. His site map, still used today, provides baseline data for underwater archaeologists.

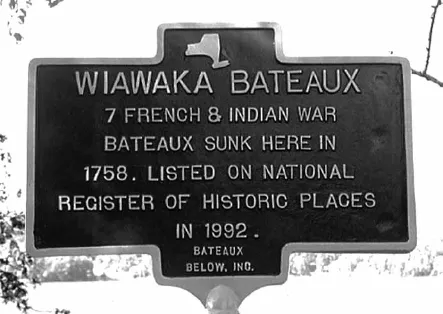

From 1987 to 1991, Bateaux Below surveyed seven vessels known as the Wiawaka Bateaux Cluster. In 1992, these seven shipwrecks were listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

This blue and yellow historical marker was erected on the grounds of the Wiawaka Holiday House. Courtesy of Joseph W. Zarzynski/Bateaux Below.

However, one aspect about the remnants of the Sunken Fleet of 1758 is mystifying. Four sunken bateaux located and mapped forty years ago have vanished.

Crandall mapped eight shipwrecks at the Wiawaka Bateaux Cluster rather than the seven there today. Also gone are 1) a bateau that had been embedded into the lake bottom at the mouth of a stream, 2) a bateau that was located off an island and 3) a bateau that was part of a group of five bateau wrecks.

After years of studying these historic vessels, Bateaux Below members think they know what might have happened to these missing warships.

On July 27, 1965, the New York Times reported that the New York State Police was conducting a “summer-training program” to recover the 1758 bateaux from the lake’s bottomlands. A photograph in that article shows divers handing bateau planks and frames to personnel aboard a state police pontoon boat.

Furthermore, prior to the Wiawaka Bateaux Cluster being opened as a shipwreck preserve for diver recreation in 1993, the site’s bateaux were visited by scuba enthusiasts, and unfortunately, some of the colonial craft were obviously disturbed. During a reconnaissance dive to the Wiawaka site by Bob Benway and Joseph W. Zarzynski on June 19, 2004, the pair may have found the location where the missing eighth bateau once rested.

On October 7, 1995, Benway and Zarzynski made a rec...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Native American Watercraft

- 2. French and Indian War Shipwrecks

- 3. Nineteenth-Century Shipwrecks

- 4. Twentieth-Century Shipwrecks

- 5. Historic Preservation & Threats to Shipwrecks

- 6. Other Submerged Cultural Resources

- 7. Replica Archaeology, Art/Science, Divers and an Urban Legend

- 8. Shipwreck Documentaries, Shipwreck Preserves and Bateaux Below

- Conclusion

- About the Authors