- 163 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A look at the plant's influence on the history and culture of the Old North State.

The days when rural life revolved around tobacco planting and harvest are gone, but many fondly remember when North Carolina was the state of farming, planting and picking tobacco. In this book, historian Billy Yeargin takes readers back to the days when communities were founded and built upon tobacco culture, and when traditions developed as industries were born. Yeargin recounts the deeply intriguing influence of tobacco on the history and culture of the state.Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access North Carolina Tobacco by Billy Yeargin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Agribusiness. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE BEGINNING: THERE WERE MARKETING PAINS

Archaeological discoveries reveal the herbal and medicinal qualities of the tobacco plant as one of the most critical factors in ancient global societies. Quite probably it was used in tribal rituals and religious ceremonies dating back to 3000 BC. Without question, however, it was used for these purposes as early as 800 BC.

Columbus recorded tobacco consumption among Native Americans when he landed here in the late fifteenth century. It was introduced to Spain in 1519. And in 1573, on his return from the Florida territory, Sir John Hawkins introduced tobacco to England for the first time. Sir Walter Raleigh is credited for introducing tobacco to the elitist circles of Great Britain when he returned from North America in 1585. In fact, England was already enjoying tobacco pleasures when Raleigh returned from the Carolina coast. His only contribution was to give prominence to the art of smoking a pipe. However, Raleigh’s great name and celebrity status drew more attention to tobacco habits than someone who might have been less notable.

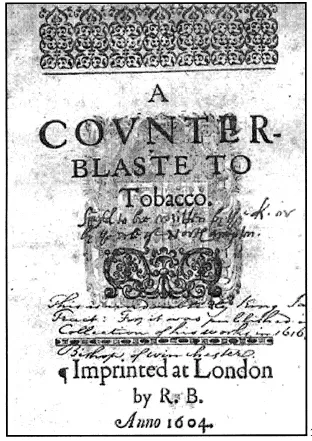

Even during this era, tobacco lacked public respect. King James, for example, suffered with an extreme distaste for it. In 1604, he issued his famous “Counterblaste to Tobacco,” warning of the detriments in consuming this “foul herb.” But even he enjoyed the economic abundance of it.

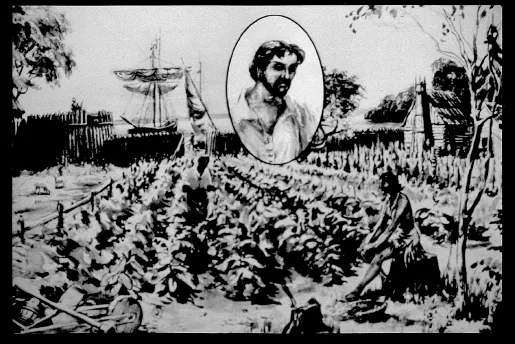

The first tobacco industry on the North American continent was started in 1612 by John Rolfe. Rolfe, more widely known as the husband of Pocahontas, shipped two hundred pounds of native tobacco from his James River farm to England. The English, who had traditionally been at the mercy of Spanish tobacco prices, immediately responded with demands for more. Knowing he would ultimately have to compete with Spanish trade, Rolfe smuggled the sweeter and milder strain of seeds from Varina, Spain, into the colonies. With great ingenuity and determination, he began producing a more desirable product. Demand from Europe rose even more. As a commemorative gesture, Rolfe named his plantation Varina Farms. Though tobacco has not been produced there in almost three hundred years, Varina continues to be a working farm today.

“Counterblaste to Tobacco,” issued by King James in 1604.

After four previous failed attempts, Rolfe’s pioneer commercial venture reversed the fate of the colonists’ effort to settle on American soil from failure to success. Thus, the British government enjoyed its first success in establishing a new colony on another continent. Tobacco trade from Jamestown made the difference. Upon returning from his first trip to England in 1616, Rolfe discovered tobacco growing all over the Jamestown settlement, even in the streets, and as far west as present-day Richmond. Colonists began to neglect planting much-needed food crops. Consequently, this mandated the first governmental intervention. In 1616, the deputy governor of Jamestown sought to balance the settler’s obsessive tobacco production by prohibiting anyone from growing it unless he grew at least two acres of corn for nourishment. At least to some extent this act provided better variation in agriculture production and encouraged the population to reap a broader subsistence from the new land. However, the New World responded to England’s skyrocketing tobacco demand with increased production of this different form of “gold.”

The colonies weren’t yet capable of manufacturing utensils, implements, foods, clothing, home supplies or other necessities. Industrially, England was centuries ahead and it provided a natural trade forum for colonial bartering in export/import goods. The stage was set for a “goods and service” trading environment between planters and Europeans.

John Rolfe is depicted as supervising cultivation of his tobacco crop at Varina Farms, west of Jamestown and about nine miles southeast of what is now Richmond, Virginia.

Until the mid-eighteenth-century French and Indian War, there was no coinage or paper currency in the colonies. Being of such great and consistent colonial value, tobacco became a necessary substitute. The process wove its way from the planter to the merchant and then to exportation. Planters were extended credit for tobacco production, and at the point of sale, all debts were paid in pounds of tobacco. Then the cycle would repeat itself: i.e., the planter reentered into debt to the merchant for the cost of another crop, plus additional goods. He would remain in debt until the next crop was sold. In turn, the merchants receiving the tobacco engaged in European trade for imported goods and, again, supplied the planter for another crop year.

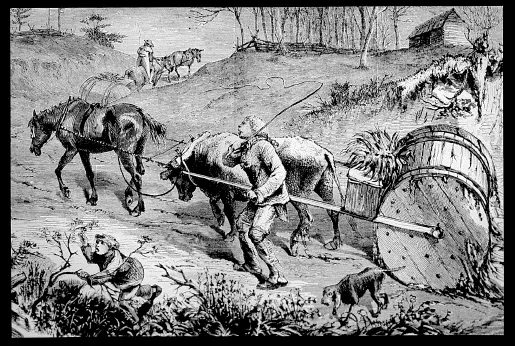

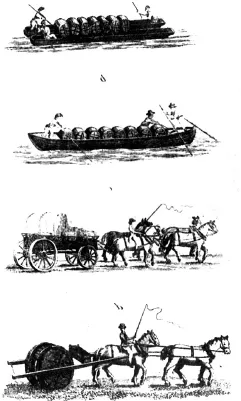

Tobacco was usually delivered at a wharf (otherwise referred to as a rolling house, tobacco magazine or storage house) located at a convenient and suitable port along the river. It was packed tightly in various sized barrels, called hogsheads. Each end, or head, of the hogshead was reinforced to accommodate insertion of a stout pole into one end, through the middle and out the other end. Enough of the pole protruded out of each end to allow attachments for pulling the hogshead, in a rolling fashion, to the shipping point by oxen, horse or other means. Upon possession by the merchant or receiver, a tobacco note was given to the planter, who then used it to pay his debts. Soon he discovered that, as a rule, the merchant didn’t thoroughly probe and examine the goods inside the hogshead. Instead, he placed it onboard the ship destined for England along with the other cargo.

A planter taking tobacco to the port nearest his plantation. Tobacco is inspected, weighed and then put aboard a ship bound for European merchants.

Even though the waterways provided the general mode of seventeenth-century transportation around Jamestown, Virginia, settlers who grew tobacco farther inland used barrels and wagons to move tobacco to the wharfs or ports. Many present-day roads in North Carolina and Virginia were carved out by these settlers as they took their tobacco to the waiting ships.

The merchant’s nonchalant attitude in assuring the quality of his newly purchased goods invited a practice among planters known today as “nesting.” “Nesting” tobacco simply means placing the good quality tobacco in the top of the hogshead and bad quality at the bottom or deep inside to conceal it from the merchant. Thus, even if the merchant should question the integrity of the planter and look inside, he surely wouldn’t tear it apart and waste a lot of time trying to qualify it. By 1619, nesting had risen to such proportions that English customers began complaining to colonial merchants and to British authorities. This resulted in the second government intervention of regulation for New World tobacco producers. This was the first general inspection law, passed by the House of Burgesses, mandating that all tobacco offered for exchange and found to be “mean” in quality by the magazine (warehouse) custodian be burnt. In 1620 and 1623 the inspection law was amended to provide for the appointment of sworn men in each settlement to condemn bad tobacco.

In 1630 a companion act was passed prohibiting the sale or acceptance of inferior tobacco in payment of debts. A commander stationed at each plantation or settlement was authorized to appoint two or three competent men to help him inspect all tobacco offered in payment of debts. If the inspectors declared the tobacco’s quality to be mean, it was burnt and the delinquent planter was barred from planting tobacco. Only the general assembly could lift this disability. From 1619 through 1785, Virginia passed numerous laws to protect the purchaser from being victimized by nested tobacco, but none were effective. With each new law the planter created more discrete and innovative methods. Being aware of this persistent and damaging practice, and not having the collective defense against it, the merchant responded by dropping the value per pound.

Sir Francis Wyatt attempted to deal with the problem by reducing the yield per planter. In 1621 he mandated that each planter limit production to one thousand plants with no more than nine leaves each, or a maximum net yield of 100 pounds. The effort was designed to discourage the planter from bringing a larger and more bulky hogshead port. The planter easily found ways to circumvent this new mandate and soon Wyatt’s order was rescinded. In 1629 the maximum cultivation each planter was allowed rose to three thousand plants, plus an additional one thousand for each nonlaboring woman and child. By this time the export figure had climbed to 1,500,000 pounds.

As with any social and economic phenomenon, the situation required some form of order, authority and organization. If colonization was to be permanent, clearly the structure of the trade must be designed to ensure social and economic progress, not just for the colonist, but the European investors as well. Colonial tobacco production was the major influence in geographic expansion along the rivers and bays of the Virginia Peninsula, the Carolinas (or Rogues Harbor as the seventeenth-century Tarheel area was referred to) and into the Delmarva (Delaware-Maryland-Virginia) Peninsula, then northward into Pennsylvania. Production was demanding on coastal soil and no effective fertilization plans or agronomic instructions were available at the time to replenish the soil from one year to the next. In order to get a satisfactory crop yield, the planter was forced to relocate and clear new fields every two or three years. Aside from the movement northward and southward, many gathered up their families and laborers and moved westward into inland areas.

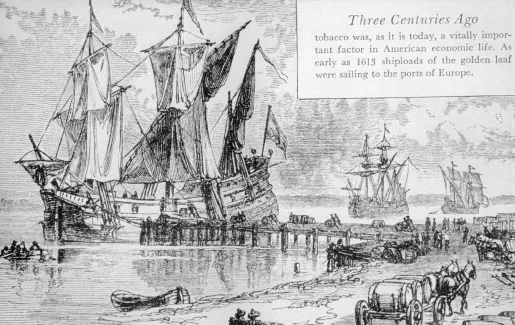

The colonial wharf was the seventeenth-century version of today’s tobacco warehouse. It is where the “American Tobacco Culture” manifested itself…the gathering place for settlers to discuss important issues such as the value of their crops, politics, social and civic matters. It was also where the value of the crops was decided.

Three Centuries Ago.

Those who owned deep-water ports enjoyed extra value by amassing several smaller crops into one shipment to European markets. This was where many disputes over the value and integrity of the crop occurred.

Other factors also promoted expansion, including the planter’s need for enough “elbow room” between himself and authority. As tobacco production began saturating the area, the abundance of navigable rivers up and down the eastern coast offered flexibility in choosing new areas of production. In a few short decades after Rolfe’s great entrepreneurial venture began, tobacco dominated and molded all mid-Atlantic social and economic life. It regulated the life of all commercial interests more than any product of a modern community.

In 1633 tobacco became the basic measure of value. Paradoxically, that same year it was demonetized by an act of the assembly, but the act was completely ignored by the people. A repeal in 1642 restored tobacco as a monetary factor. Thereafter, only debts contracted in tobacco were recoverable by law.

The golden leaf was accepted as payment for taxes, purchasing wives and even as payment to preachers and the settlement guards (the military). In 1660 the Lord Proprietors of Carolina organized a plan to officially colonize what is now North Carolina. King Charles II granted a vast area from Spanish Florida to the southern border of Virginia and from the Atlantic to the Pacific, to become the Carolinas. One condition of that grant was that settlers of this area would not produce tobacco. This was done largely to appease Virginia and Maryland leadership, who complained that opening up territory to the south, would only add more trade competition and increase the already over-produced crop. However, settlers seeking new tobacco soil had already entrenched themselves in the “Rogues Harbor” area and had begun tobacco production before Charles II granted the colony. The increasing movement to the outskirts of settled territory, along with the ingenuity of planters, gave constant and effective resistance to the regular barrage of laws dealing with nesting tobacco. By 1644 the practice was so obvious that merchants and dealers collectively turned to English rule for assistance in arresting the problem. Planters had begun to hide tobacco stalks, tree leaves and other worthless objects deep inside hogsheads. Even liquor, starch and spikes were retrieved when the hogshead was opened at its final destination. Any bill Parliament could produce only served to sharpen the planters’ imaginations.

In 1666 Virginia leaders convinced producers in the Carolinas and Maryland that supply was exceeding demand and that it would be in the interest of all tobacco colonies to abstain from production for one year. An agreement was made to this effect, only to be vetoed by Lord Baltimore. Carolina planters responded to the veto by opening up more cultivatable land below the Virginia border. In 1669 the Albemarle Assembly of North Carolina passed a law designed to attract more settlers into Carolina. Virginians, already hostile to the Carolina settlers because of increased trade competition, passed a law in April 1669 that prohibited tobacco from being shipped directly out of the Carolina Colony into Virginia or other trading areas. For the one hundred years that this act remained in place, “Rogues Harbor” ignored it, and the Southern colony’s tobacco trade felt no real effect from it. The planters were as astute at smuggling into Virginia, or bypassing Virginia’s patrolling forces, as they were in continuing to nest tobacco. By 1731 London’s Privy Council finally recognized the economics of commerce in the Carolinas and repealed the law of 1679. Even so, all tobacco produced, whether in Virginia or Carolina, was referred to as “Virginia” tobacco.

Between 1619, when the first law dealing with nesting tobacco was imposed, and 1730, numerous legislative efforts were brought forth to deal with the issue. All inspection laws passed between 1619 and 1641 were repealed, except the Act of 1630, which prohibited the sale or acceptance of inferior tobacco in payment of debts. The Act of 1630 remained in force until 1760. In 1723 the general assembly passed an act authorizing the county courts to build warehouses at public expense. For the sake of expediency and to ensure closer observation and policing of inspection laws, these were to be built within a mile of a public port or landing. Governor Spotswood of Virginia introduced an act requiring licensed inspectors at warehouses. This act was opposed by Colonel William Byrd and ultimately vetoed by the Privy Council of London.

Colonization of the New World was moving into a second century. The vested interest of European financiers and governments were being born from the colonial tobacco fields. And greed was deeply ingrained through this trade. Regulation and government enforcement, designed to ensure maximum profit for the mother country, was made difficult because of the distance between the governed and the governors. Even with regular visits and monitoring by English rule, as well as a host of appointed colonial authorities, it was impossible for the Crown to maintain an objective view of the day-to-day business proceedings on American soil. While nested tobacco continued to pour into Europe, the distance and lack of perception of the nature of the proceedings at the local level rendered the Crown unable to comprehend a true formula for correction. That, to a large extent, was left to local authorities, who even at close range had serious problems dealing with this persistent problem.

In 1730, after 110 years of legislative failure, the Virginia General Assembly passed the most comprehensive inspection bill ever introduced. In part, it provided that no tobacco was to be shipped to England in hogshead cases or casks without having first been inspected at one of the legally established warehouses. Two inspectors were employed at each warehouse, and a third was summoned to settle disputes between the two regular inspectors. These officials were bonded and forbidden, under heavy penalty, to pass bad tobacco, engage in tobacco trade or take rewards. Tobacco offered in payments of public or private debts had to be inspected under the same conditions as that to be exported. The inspectors were required to open the hogsheads and extract and carefully examine two samples. All trash and unsound tobacco was to be burned in the warehouse kiln in the presence of the owner and with his consent. If the owner refused consent, then the entire hogshead would be destroyed. After it was sorted, the good tobacco was repacked and the planter’s distinguishing mark, the net weight, tare weight and the name of the inspector and the warehouse were stamped on the hogshead. In part, this act was a desperate effort by the government to lay to rest, once and for all, the planter’s bad habit of nesting. Also, for the first time, this act addressed the increasing need for a more orderly marketing system.

The last remaining colonial tobacco warehouse, or as it is sometimes referred to, wharf, or “magazine,” in Urbana, Virginia. This building, erected sometime between 1690 and 1710, now houses a library.

Europeans who, for many reasons, were dissatisfied in the mother country and who had heard about the promise of riches from tobacco production in the New World, opened up a continued wave of migration into Virginia’s tidewater and Carolina’s coastal area. By the turn of the eighteenth century, tobacco exports from Carolina had risen to eight hundred thousand pounds annually. Combined exports out of Virginia and Maryland and into Europe were now exceeding twenty-two million pounds. Along with this trend in production volume came the intensity of the nesting problem. The Carolina colony, now rapidly becoming a major tobacco exporter out of Port Roanoke (Edenton), suffered the same nesting problems as its neighbors to the north. Tobacco shipped out of that port to Scotland was perpetually nested with undesirable materials. Inevitability, Carolina would be forced to adopt an inspection act of its own in 1754. Like all others before, these comprehensive bills failed to bring real relief to the nesting problem.

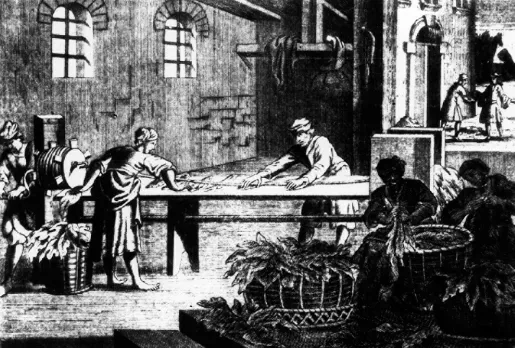

Tobacco being prepared for market. In some cases, this process was done before the tobacco was presented for inspection. In others, it was done after purchase by the local merchant who, in turn, loaded it for passage to Europe.

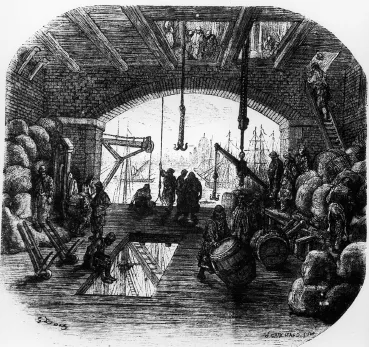

While production and marketing of raw tobacco flourished in the colonies, processed tobacco became a tremendous business in all European areas. Here is a scene of a tobacco-receiving warehouse on the Thames River in England.

While marketing began to take some form of order and organization, disputes over quality and prices persisted between seller and buyer. The buyer would use price reduction to offset against the prospects of receiving undesirable tobacco. The planter would cry foul. The government inspect...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Tobacco Days

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- The Beginning: There Were Marketing Pains

- “The Duke Homestead,” by Linda Funk

- The Tobacco Auctioneer

- A Story of the Tobacco Market Opening in Smithfield, North Carolina

- Courier-Times Accounts of the First Tobacco Market Opening in Roxboro

- “First Warehouse Believed Erected in Oxford in 1866,” by Frances B. Hayes

- “Tobacco Tales, Told from the Ground Up,” by John Barbacci

- “Tobacco, Seen ‘from Other Side of Desk’”

- “Tobacco Towns: Urban Growth and Economic Development in Eastern North Carolina,” by Roger Biles

- “Fifty Years of Tobacco: How Did We Get to Where We Are?” by John H. Cyrus

- “Between You and Me,” by Carroll Leggett

- “Question & Answer with Pender Sharp,” by Rocky Womack

- “Hicks Honored by Stabilization,” from Flue-cured Tobacco Farmer Magazine

- “Remarks to Tobacco Workers’ Conference,” by J.T. Burn

- Tobacco Terms