- 131 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A "compelling" account of the little-known bloody skirmishes that took place in this picturesque part of West Virginia (

Civil War Monitor).

The three rivers that make up the Coal River Valley—Big, Little and Coal—were named by explorer John Peter Salling (or Salley) for the coal deposits found along their banks. More than one hundred years later, the picturesque valley that would separate from Virginia a short time later was witness to a multitude of bloody skirmishes between Confederate and Union forces in the Civil War.

Often-overlooked battles at Boone Court House, Coal River, Pond Fork, and Kanawha Gap introduced the beginning of "total war" tactics years before General Sherman used them in his March to the Sea. Join historian Michael Graham as he expertly details the compelling human drama of the bitterly contested Coal River Valley region during the War Between the States.

Includes illustrations

The three rivers that make up the Coal River Valley—Big, Little and Coal—were named by explorer John Peter Salling (or Salley) for the coal deposits found along their banks. More than one hundred years later, the picturesque valley that would separate from Virginia a short time later was witness to a multitude of bloody skirmishes between Confederate and Union forces in the Civil War.

Often-overlooked battles at Boone Court House, Coal River, Pond Fork, and Kanawha Gap introduced the beginning of "total war" tactics years before General Sherman used them in his March to the Sea. Join historian Michael Graham as he expertly details the compelling human drama of the bitterly contested Coal River Valley region during the War Between the States.

Includes illustrations

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Coal River Valley in the Civil War by Michael B Graham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

PRELUDE

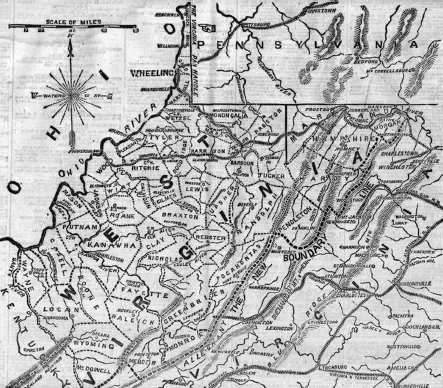

In the first few months of the Civil War, the South faced its first serious challenge in the mountains of western Virginia. In Washington, politicians, railroad and business interests and civilian groups urged President Abraham Lincoln and the general in chief of the U.S. Army, General Winfield Scott, to occupy western Virginia with Federal forces. Foremost, the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad crossed the northwestern part of the region. Enormous financial investments had been made in the railroad that would be critical to moving troops and supplies in the war. Both sides foresaw the significant strategic benefits. Therefore, the North and South each coveted the B&O Railroad, and it became a guiding strategic concern of both the Union and Confederate forces.

There were other important reasons, as well, to control western Virginia. Second, occupying western Virginia would also disrupt Confederate recruiting in the region, depriving the South of a significant source of manpower for its armies. Third, occupying the region would deny the Confederacy access to the mountains’ abundant strategic natural resources of coal, oil, saltpeter, wool and, especially in the Kanawha Valley, salt. Finally, for political reasons, it seemed important for the North to support the pro-Union elements among the western Virginia population disaffected with the Old Dominion.12

The Confederacy was similarly motivated to hold western Virginia. If the mountains could be retained, the North would be squeezed to a narrow corridor of only about one hundred miles between the Great Lakes and Virginia through which to transport western troops and supplies overland to the East. The Confederates hoped to move north and westward to take over, or at least break, the B&O Railroad that brought men and supplies eastward from Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin. Finally, the South wanted to control the northwestern part of Virginia to stop the newly formed pro-Union Restored Government of Virginia at Wheeling from progressing. Throughout the region, the Confederacy initially was able to gather only a scattered token force of fewer than one thousand troops to repel invasion from Ohio and Pennsylvania and hold on to western Virginia.

West Virginia. A primary focal point early in the Civil War, both sides were anxious to control the Old Dominion’s vast western mountain wilderness region. West Virginia Department of Natural Resources.

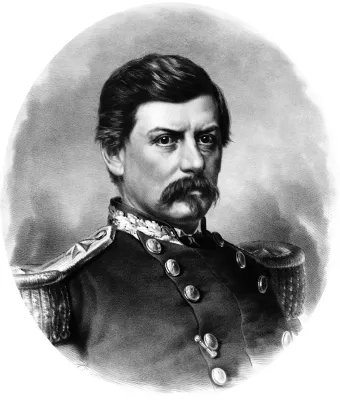

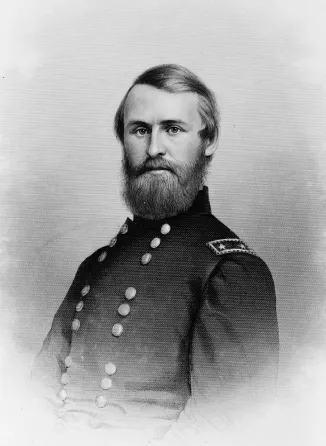

In response, a general counterplan was conceived in the North. Major General George B. McClellan, in overall command of the Army of Western Virginia, would cross the Ohio River and drive out the westward-facing Confederate forces organizing to defend the region. McClellan’s invasion had two wings. He directed the northern wing, while Brigadier General Jacob D. Cox directed the southern. Together, the two wings would invade and secure the region for the North. In May 1861, General McClellan, with twenty thousand men under his control, advanced from Ohio.13

Union major general George B. McClellan commanded the Federal army that invaded western Virginia in the summer of 1861. Library of Congress.

McClellan’s campaign opened with startling success as the Confederates were routed in a series of brisk battles, and within six weeks, the North’s conquest of northwestern Virginia was completed. For the South, the defeat of the Confederate forces was ruinous and viewed as a tremendous blow. The Union had control of both the Ohio River and the B&O Railroad.14 The successes made McClellan a national hero and launched him to command of all the Federal armies. More importantly, the catastrophic flight of the Confederate forces enabled the work of the Union political elements in the region to continue their advancement of a new state, West Virginia, without interruption.15

Southward, General Cox carried out his part of the invasion of western Virginia. He crossed the Ohio River in July, landed with a brigade at Guyandotte and continued east toward the Kanawha Valley city of Charleston.16 Cox’s force first encountered resistance at Barboursville (July 14). The Federals met six hundred Rebel militia dug in atop a ridge paralleling the Mud River and dominating the covered Mud River Bridge. The action was as sharp as it was brief. The Southern troops waited for the Federals to cross the bridge before firing, inflicting serious casualties. After an exchange of fire, the Federals conducted an uphill bayonet charge, driving the Rebels from the ridge, and took the town. Confederate losses were one mortally wounded and three to five injured, while five Federals were killed and eighteen wounded.

Union brigadier general Jacob D. Cox commanded the Federal forces under McClellan that invaded the Great Kanawha Valley in the summer of 1861. Library of Congress.

As Cox pressed eastward, Confederate resistance strengthened around Charleston, the center of Rebel control in the Kanawha Valley. At the crossing of Scary Creek, a tributary of the Kanawha River, Cox’s leading regiments and six hundred Confederate infantry, cavalry and artillery clashed on July 17. Four hours of hard fighting were needed to drive back the Federals. Considering the number of troops engaged, Federal losses were heavy, including fourteen killed, thirty-three wounded and twenty-one captured or missing. The Confederates lost five killed and twenty-six wounded and two pieces of artillery.17

The Rebel victory’s effects were temporary as the fight at Scary Creek merely slowed Cox. With more Federal forces closing from the north and west, the Confederate commander, former Virginia governor Brigadier General Henry A. Wise, abandoned the Kanawha Valley and retreated 125 miles to Lewisburg.18 In the Confederate retreat, Major Thomas L. Broun led a force of three hundred Rebel volunteers from Boone and Logan Counties up the Big Coal River through Boone and Raleigh Counties, southwest of Charleston, in the war’s first large movement of military forces through the Coal River Valley region. Broun knew the land well since he recently had been the prewar president of the Coal River Navigation Company at Peytona, a post held before him by future Union army general William S. Rosecrans.19

Instead of stopping at Charleston, General Cox pursued the fleeing Confederates up the Kanawha Valley and marched his army thirty-eight miles directly to Gauley Bridge, entering the town on July 29. Cox’s swift seizure of Gauley Bridge was one of the more significant early strategic achievements of the war in the mountains. The Federals’ possession of Gauley Bridge, with its concentration of strategic lines of river and road communications throughout the region, significantly impeded Confederate resistance in south-central western Virginia. The Confederates were well aware that this force blocked their return to the Kanawha Valley and would need to be removed. Therefore, the forces of Brigadier Generals John B. Floyd and Wise engaged in numerous probing skirmishes in a wide arc to the south, southeast and northeast of Gauley Bridge, notably Big Sewell Mountain (August 16), Hawks Nest (August 20), Piggots Mill (August 25) and Kessler’s Cross Lanes (August 26).

Meanwhile, violence and civil unrest intensified in the areas around the Kanawha Valley during the summer, especially in the Coal River Valley region, the rugged mountainous coal-rich lands astride the Big and Little Coal Rivers and their seemingly innumerable creeks and streams. Control of the Coal River region became an objective for both sides. The valley “was torn by internal strife between unionist and secessionist sympathizers. Although Raleigh County as a whole voted for secession, the Marsh and Clear Fork districts of the Coal River were strong Union sympathizers. Many neighbors and families were split, some sending soldiers to both the Union and Confederate armies.”20

Coalsmouth (present-day St. Albans), at the confluence of the Coal and Kanawha Rivers in Kanawha County, became a major base for the Confederate army early in the war and afterward for the Union army. Before he retreated, “General Wise scuttled many barges of coal in an effort to block Union troop navigation up the Coal river and prevent the coal from ending up in Union hands.”21

The adjacent countryside, however, swarmed with secessionists. The worst turmoil was in Boone County—named in honor of the famous pioneer Daniel Boone—where, throughout the summer in 1861, “the troops under Wise and the militia south of the river kept up a continual skirmishing.”22 On April 17, the county had passed the ordinance of secession, 317 to 226 in favor, and declared strongly for the Confederacy. Most county officials and “residents were on the side of the South.”23 The county’s enlistment rate was two-thirds Confederate.24 Rebel citizens and armed volunteers—characterized as “robbers and murderers” by the Northern press—harassed residents sympathetic to the Union.25 In turn, armed Union volunteers—self-styled “Home Guards”—harassed residents sympathetic to the Confederacy. To defend against thieving and to protect their property, communities began organizing for self-defense.26

In great majority, the citizens were Confederate in sympathy; though there were in spots communities that held fast to their loyalty and allegiance to the old Union. It was these spots that were favorite targets for roving bands of Confederate partisans—for the most part irregulars who preyed upon the Federal loyalists and kept the entire area in a state of turmoil. There were reprisals and house burnings by the Unionists, which was held to be “rebellion” by the Confederate dissidents.27

The situation was only marginally less tenuous in the Clear Fork region, as the diary of a Coal River Valley resident attests:

The day before the election a neighbor of mine, who had professed all the time to be a Union man, came to me and told me that the Union was gone for certain and that we all had better vote for ratification and all secede together and show as bold a front as we could. He said that it would be better for us to divide the Union and set up a new government of our own and call it the Southern Confederacy. He also said his brother was a kind of a lawyer who lived at Raleigh Court House (Beckley) and had been down and explained the matter to him, and also told him that the colonel of the militia of our county would be down to our precinct at the election the next day, and would bring the sheriff and deputy sheriff of our county and armed forces to guard the polls. He said that all who voted for rejection of secession would forthwith be arrested and hanged. He also told me that they had a particular eye on me and if I voted a Union vote I would be certain to be killed…I soon found that all of the Union men would be compelled to keep their thoughts to themselves and not express them to no man, because the rebels had got to such a pitch that there were being quite a number of Union men shot and hanged. So I said as little as possible.28

From the New York Herald, December 14, 1862.

The historical record does not reveal exactly when the Coal River Valley region first arose to Federal attention in the spring and summer of 1861. However, because of the increased danger of war between the North and South and the animated public debate about the West Virginia statehood movement, public meetings were held at largely pro-Union Peytona and pro-Confederate Boone Court House with resolutions calling on the people to prepare for war and steps taken to raise troops. The April 19 Virginia secession ballot was controlled by Confederate sympathizers who prevented the Union sympathizers from voting, and the Confederate flag was hoisted over the county courthouse on April 20 at a mass meeting at Boone Court House.

The state of affairs was comparable in the Clear Fork and Marsh Fork areas of the upper Coal River Valley in Raleigh County:

As the rebels got a few men together, they made great threats against the Union men and all who would not vote for the ratification of the Ordinance of Secession and canvassed every county, threatening to mob every man who spoke in favor of the Union, saying at the same time that they would establish a Southern Confederacy. They said that every man who voted for the Union was a black abolitionist and that as soon as they voted for the Union they would mob him, hang him and shoot him before he left the ground. By that means they kept a great many Union men from going to the polls.29

As Civil War historian Bruce Catton wrote of this early period of the war, “The border states appeared to be exploding like a string of firecrackers”:

Against them was the power of a blazing sentiment, built on an old fondness and raised now by violence to story-book intensity. The bond that pulled American states into the Confederacy was always more a matter of emotion than of cold logic, and…the emotional response to the nineteenth of April was unrestrained. What the North saw as a mob scene looked in the South like a legendary uprising, with gallant heroes brutally done to death by the ignorant soldiers of a cruel despotism.30

Such “welling forth of sentiment” that attached itself to the Southern saga was rampant in southwestern Virginia, which largely felt kinship with the Old Dominion.

Meanwhile, General McClellan, in Union command of western Virginia, needed information about secessionist strength and movements and relied on spies. He sent Union spy Pryce Lewis, an agent of the famed Pinkerton detective organization, to the region, which resulted in “one of the most spectacular feats of espionage in the early days of the war.” After several weeks collecting intelligence, Lewis made his escape via the Coal River Valley along the Boone–Logan road.

Union spy Pryce Lewis (Pinkerton Detective Agency) performed intelligence gathering in the Kanawha Valley in the summer of 1861 for General McClellan. Lewis escaped the Confederate-controlled region via the B...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Prelude

- 2. Boone Court House

- 3. Coal River

- 4. Pond Fork

- 5. Kanawha Gap

- 6. Aftermath

- Appendix A. Biographies

- Appendix B. Casualties

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author