- 163 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Civil War Springfield

About this book

An account of Springfield, Missouri, population 1,500—and the epic struggle between the Union and Confederacy to control it.

During the Civil War, Springfield was a frontier community of about 1,500 people, but it was the largest and most important place in southwest Missouri. The Northern and Southern armies vied throughout the early part of the war to occupy its strategic position. The Federal defeat at Wilson's Creek in August of 1861 gave the Southern forces possession, but Zagonyi's charge two and half months later returned Springfield to the Union.

The Confederacy came back near Christmas of 1861—before being ousted again in February of 1862. Marmaduke's defeat at the Battle of Springfield in January of 1863 ended the contest, placing the Union firmly in control, but Springfield continued to pulse with activity throughout the war. In this volume, historian Larry Wood chronicles this epic story.

Includes illustrations

During the Civil War, Springfield was a frontier community of about 1,500 people, but it was the largest and most important place in southwest Missouri. The Northern and Southern armies vied throughout the early part of the war to occupy its strategic position. The Federal defeat at Wilson's Creek in August of 1861 gave the Southern forces possession, but Zagonyi's charge two and half months later returned Springfield to the Union.

The Confederacy came back near Christmas of 1861—before being ousted again in February of 1862. Marmaduke's defeat at the Battle of Springfield in January of 1863 ended the contest, placing the Union firmly in control, but Springfield continued to pulse with activity throughout the war. In this volume, historian Larry Wood chronicles this epic story.

Includes illustrations

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

The Prewar Years

Kansas Bleeds into Southwest Missouri

The bombardment of Fort Sumter by Confederate artillery in April 1861 marked the official beginning of the Civil War, but it is scarcely a stretch to suggest that the war actually began several years earlier on the Kansas-Missouri border during the battle over Kansas statehood that came to be known as “Bleeding Kansas.” In fact, the roots of the Civil War can be traced even further back, at least to the birth of the nation, when sectional disagreement over the issue of slavery led to the adoption of the “three-fifths” compromise in the United States Constitution. The slavery issue was still festering in 1820 when the Missouri Compromise stipulated that Missouri would be admitted to the Union as a slave state (while Maine was admitted as a free state) but that no additional states lying north of Missouri’s southern border could be admitted as slave states. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, however, effectively nullified the Missouri Compromise by opening those two new territories to white settlement and stipulating that, in the name of “popular sovereignty,” the people residing in the territories would decide for themselves whether they wanted to allow slavery within their boundaries.

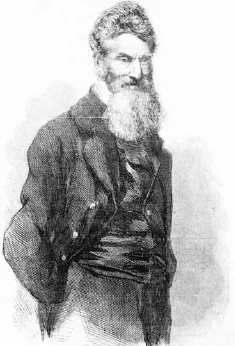

Nebraska, by virtue of its more northerly location, was destined from the beginning to be a free territory, and the question of slavery was never in doubt there. However, the Kansas-Nebraska Act ushered in a period of strife and violence in Kansas that presaged the Civil War. Already surrounded on the north and east by the free states of Iowa and Illinois, the slaveholders of Missouri felt threatened by the prospect of a free state to their west that would form the third link in an encircling chain of free-soil territory. A free Kansas might serve as a haven for stolen and runaway slaves and spell doom for the slaveholding interests of wealthy Missourians. In response to the threat, prominent landowners organized squads of men during the mid- to late 1850s to trek to Kansas to vote illegally in territorial elections on the proslavery side and to otherwise oppose the free-soil settlers who had begun flooding into Kansas from the Northern and New England states. Earning the name “Border Ruffians,” the Missourians, in their zeal and devotion to their cause, sometimes resorted to violence, as did rabid abolitionists like John Brown on the free-soil side.

In eastern Kansas, rabid abolitionists like John Brown clashed with “Border Ruffians” during the prewar years. From Frank Leslie’s Weekly, courtesy of Library of Congress.

Most early residents of the Missouri Ozarks were poor hill folk who had come from the upper tier of Southern states, especially the Appalachian region of those states. The vast majority did not own slaves, and their economic interests lay increasingly with the North. However, they were tied to the South by bonds of kinship and culture, and they tended to support the wealthy landowners and slaveholders who dominated Missouri politics. Thus, the people of Springfield and Greene County, according to Holcombe’s 1883 history of the county, “took a more or less conspicuous part…upon the pro-slavery side” in the Bleeding Kansas conflict. In addition to sending its fair share of Border Ruffians to stuff the Kansas ballot boxes, Greene County was also home to a secret proslavery organization akin to the Knights of the Golden Circle. The clandestine society maintained three or four lodges in different locations throughout the county, and members of the cloak-and-dagger outfit hailed one another with esoteric signs, grips, and passwords.

In July 1856, about a dozen men from Greene County joined a proslavery party from southwest Missouri for a journey to Kansas to fight the abolitionists, but when they reached the border, they found that recent hostilities in the region had already ceased and that their services were not needed. In August of the same year, “Judge” R.G. Roberts of Fort Scott, Kansas, spoke at Springfield in support of the proslavery cause and stirred up the like-minded men of Greene County. Shortly afterward, on September 1, the proslavery men of the county congregated for a mass meeting at the courthouse on the Springfield square. Several prominent citizens gave stirring speeches denouncing abolitionism, and the gathering adopted resolutions condemning the free-soil movement and pledging support for the proslavery people of Kansas. A number of men in the crowd enrolled as “minutemen,” pledging themselves to go to Kansas at a moment’s notice to fight the abolitionists, and a large sum of money was raised in support of the proslavery cause in Kansas.

The proslavery fervor that characterized southwest Missouri and Greene County during the Bleeding Kansas years, however, did not translate into secessionist sentiment as the Civil War approached. Although proslavery feelings in the region were widespread, the sentiment against disunion was even stronger. The proceedings of a series of meetings held in Springfield during the spring of 1858 illustrate the strength of this middle-of-the-road sentiment in the Greene County area.

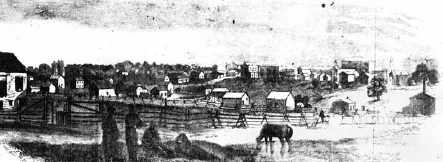

Springfield was a small, rural town at the beginning of the Civil War. Sketch from Harper’s Weekly by Alexander Simplot.

A large group of citizens, with Greene County probate judge Sample Orr presiding, met on April 5 with the idea of establishing a “Union Party,” the only rallying cry or motto of which would be the preservation of the “Federal Union.” The group stated its belief, according to the Jefferson City Inquirer, that “the tendency of what is termed National Democracy is the same as that which is termed Black Republicanism, both parties aiming at a dissolution of the Union, and therefore unworthy of trust.” The meeting adopted a resolution condemning attempts in either the North or the South to establish two parties, antagonistic toward each other and sectional in nature that, should these efforts be consummated, would “most surely end disastrously to this government, by destroying the bonds of Union.” The gathering also adopted a resolution condemning the Kansas-Nebraska Act as having produced “evils, civil war, bloodshed, murders, robberies, house burning, and such like enormities and crimes” and opposing the proslavery Lecompton Constitution, then pending in Congress, on the grounds that it had not been fairly voted on by the people of Kansas. Despite their opposition to the proslavery constitution, the men at the meeting wanted it clearly known that they rejected “with indignation and scorn the base attempts of a few government fed editors and unprincipled demagogues to class Union and conservative men with Abolitionists and Black Republicans for refusing to co-operate with the so-called National Democracy in their foul crusade against the Union.”

Clearly, by 1858, allegiance to the Union was beginning to supplant allegiance to the Democratic Party as the predominant political sentiment in southwest Missouri. As the editor of the Springfield Mirror remarked in the wake of a second Union meeting a few weeks later, “The fact there is a party in the Southwest, so long the stronghold of the so-called National Democracy, in favor of the Union of the States, as they are, is becoming more and more manifest.”

A third mass meeting of unionists in late May reaffirmed the resolutions of the first two meetings. The dedication to the Union, regardless of party, espoused by a growing number of men in Greene County and throughout the country in 1858, along with their mounting disgust with the secessionist faction of the Democratic Party, foretold both the rise of the Constitutional Union Party and the split in the Democratic Party that resulted in the nomination in 1860 of four different candidates for president of the United States.

In the state of Missouri as a whole, three distinct political camps developed during the months leading up to the Civil War. The Unconditional Unionists, a good number of whom were also abolitionists, vowed to support the Union regardless of what might happen. They made up a relatively small portion of the state’s people and were concentrated in the St. Louis area, principal home to Missouri’s fiercely loyal German population. The secessionists formed another small minority of the state’s population. They dominated in certain rural areas throughout the state and were represented disproportionately in the state legislature. The overwhelming majority of Missouri’s citizens, however, were Conservative or Conditional Unionists. Many of them had ties to the South, and most opposed abolition but pledged to support the Union as long as the Federal government did not invade or otherwise coerce the Southern states.

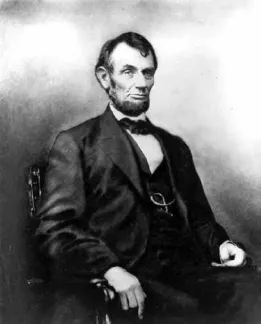

The 1860 presidential election results in Missouri illustrate this three-way political division in the state and the ascendancy of the middle-of-the-road position. Abraham Lincoln, the Republican candidate, received only 17,028 votes in the state, and John C. Breckinridge, the candidate of the Southern Democrats, received only 31,317. Meanwhile, the two centrist candidates, Stephen Douglas of the Northern Democrats and John Bell of the Constitutional Union Party, received more than 58,000 votes each.

Conservative Unionism dominated in southwest Missouri and Greene County, as it did in the state as a whole. The Constitutional Union ticket, which featured Judge Orr as the gubernatorial candidate, was particularly strong in Greene County, where Bell, endorsed by the Springfield Mirror, polled 986 votes. Breckinridge received 414 votes and had the endorsement of the Springfield Equal Rights Gazette, which had recently been started specifically to promote the Southern Democrats. Douglas garnered only 298 votes, despite the support of Springfield’s leading newspaper, the Springfield Advertiser, while Lincoln received a mere 42. (The Republican party had gotten not a single vote in Greene County in the 1856 election.)

As suggested by Lincoln’s meager vote total in Greene County, “Republicans in Southwestern Missouri in 1860 were,” in the words of Holcombe’s county history, “few in number and widely scattered.” Republicanism was in such “bad odor” in Greene County that the party’s few adherents resorted to meeting in secret for fear of being driven from their homes, and they developed a system of signs and grips by which they recognized one another. In fact, when it was announced that forty-two men in Greene County had voted for Lincoln, the number was considered remarkably large, as it had previously been thought that there were only a dozen or so Republicans in the county.

Abraham Lincoln received only forty-two votes in Greene County in 1860. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Not surprisingly, most Greene County citizens, therefore, greeted the news of Lincoln’s victory in November 1860 with disapproval, but the large majority, including some of the men who had voted for Breckinridge, expressed strong support for the Union and resolved to abide by the result of the election. For some of them, though, this sentiment soon changed after South Carolina seceded in December and other Southern states followed. The very fact that most southwest Missourians were not extremists, but instead attempted to chart a middle-of-the-road course, sometimes caused them to vacillate. As the 1883 county history suggested, the only thing certain about the sentiments of men in those days was that “they were liable to change. Secessionists one week became Union men the next, and vice versa.” Even in the face of the secession of the Southern states, however, the vast majority of Greene County residents and other southwest Missourians still hoped that civil war could be avoided, and they adopted a wait-and-see attitude.

They didn’t have to wait long. In early January 1861, retiring Missouri governor Robert Stewart, in his farewell message, urged a middle-of-the-road course of “armed neutrality” for his state, a position that reflected the views of the majority of the people, but incoming governor Claiborne F. Jackson declared in his inaugural speech that Missouri’s interests lay with the seceding states. He, however, recommended a state convention that would allow the people of Missouri and their representatives to decide for themselves the issue of secession.

The election of delegates to the convention took place in mid-February. In the Nineteenth Senatorial District (which included Greene County), Union candidates Sample Orr and Littleberry Hendricks of Springfield and R.W. Jamison of Webster County defeated the three secessionist candidates, including N.F. Jones and Jabez Owen (son-in-law of Springfield founder John Polk Campbell) of Greene County, by a margin of about four to one, each polling about 80 percent of the vote. (Holcombe’s 1883 Greene County history called the unionists “unconditional Union” men and the secessionists “conditional Union” men. However, most of the so-called conditional Union men harbored secessionist sentiments, and even a good number of the unconditional Union men, as the author admitted, later ended up fighting on the Confederate side or at least sympathizing with the Southern cause.) Meeting in St. Louis in early March, the state convention voted overwhelmingly to stay in the Union but also adopted a resolution opposing any attempt by the Federal government to coerce the seceding states or the use of military force by either side. During the first few months of 1861, the growing national divide stirred the people of Springfield and Greene County to take a keen interest in political affairs. They freely discussed the possibility of civil war, and some people began preparing for such an eventuality. A few openly sympathized with the seceding states, but most continued to espouse the Conservative Union position, declaring that they were neither secessionists nor abolitionists.

The prospect of war during the early months of 1861 not only generated lively public discussion but also prompted Union men and secessionists alike to begin organizing and holding meetings throughout the county. Robert P. Matthews, who joined a “Union League” in Greene County during the months leading up to the war, recalled, “All these organizations were mainly of a secret nature, meeting at night with guarded doors, and a system of passwords, ceremonies known only to the initiated.” Such precautions, he explained, were not necessary in the Deep South or the upper Northern states, where nearly everyone was of the same mind. “But here on the border it was quite different. You did not know who was friend or who was foe.”

One of the larger prewar unionist meetings in the area was held near the end of March in the southwest part of Greene County near the Christian County line, not far from where the Battle of Wilson’s Creek was later fought. Prominent citizens from throughout southwest Missouri, including Littleberry Hendricks and Marcus Boyd from Springfield, attended as delegates to discuss the state of affairs in their respective counties.

The secessionists, although in the minority, were equally active. On the evening of March 25, N.F. Jones gave a speech to a secessionist gathering on the Springfield square, and the group, according to the Advertiser, promenaded on the streets “under a strange flag.” Three days later, on the twenty-eighth, U.S. Treasurer W.C. Price, a former Greene County probate judge, returned to Springfield from Washington and joined a demonstration of secessionists in another procession, this one headed by a small brass band. On Saturday afternoon, March 30, a larger group of secessionists gathered in Springfield, and a Confederate flag was raised over a private residence. Some of the Union men of the town became indignant, and the two sides had a standoff with pistols drawn before the flag was taken down, and the two parties dispersed without bloodshed or violence.

Even as mounting tension between unionists and secessionists led to incidents like the late March standoff in Springfield, and even as men on both sides prepared for war, most residents of Greene County continued to hope that such a calamity might be averted—or at least that Missouri might be able to stay out the conflict. The Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, however, destroyed any prospect of compromise or remaining neutral. Like the rest of the country, southwest Missouri would be drawn into a great civil war, whether its people liked it or not.

Chapter 2

The Guns of Fort Sumter Echo in Springfield

Springfield received word of the attack on Fort Sumter by telegraph, and the Advertiser ran an extra edition announcing the event. Stirred to intense excitement by the news, the townspeople huddled on every corner, discussing the incident and what it might mean for the future course of the country.

In response to the firing on Fort Sumter, President Lincoln issued a call for seventy-five thousand troops to repress the rebellion, and Missouri was asked to furnish four regiments as its share. Governor Jackson refused to comply, denouncing Lincoln’s call to arms as an “unholy crusade.” Instead, the governor got a resolution passed through the Missouri legislature condemning any Federal attempt to coerce the seceding states, and he also began trying to organize a state militia for the defense of Missouri against possible invasion. Although lawmakers balked at approving the latter effort, Southern sympathizers throughout the state nonetheless began organizing under the proposed “military bill,” and a group seized the Federal arsenal at Liberty, Missouri, on April 20 to arm the budding militia.

Loyalists throughout the state also began organizing and arming themselves as home guard forces, and they were particularly active in Springfield and Greene County, where Unionism was more dominant than in many other parts of the state. Springfieldian John S. Phelps, congressman from Missouri’s Sixth District (which included Greene County), hurried home from Washington at the outset of the war, and on Saturday, May 4, he and other prominent citizens (like Judge Orr) addressed a large Union meeting at the bank building on the north side of the Springfield square. Toward the end of the meeting, an Arkansas man named A.M. Bedford was given an opportunity to present the secessionist point of view.

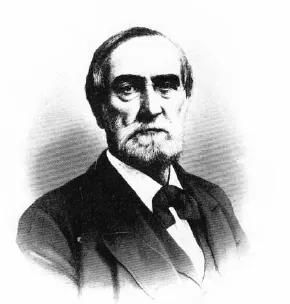

A future governor of Missouri, John S. P...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. The Prewar Years: Kansas Bleeds into Southwest Missouri

- Chapter 2. The Guns of Fort Sumter Echo in Springfield

- Chapter 3. The Yankee Dutch Come to Town

- Chapter 4. Wilson’s Creek: A Perfect Panic

- Chapter 5. The Confederates Take Over the Town

- Chapter 6. Zagonyi’s Charge

- Chapter 7. The Federals Reoccupy Springfield

- Chapter 8. The Rebels Move Back In

- Chapter 9. The Union Takes Over Again

- Chapter 10. Marmaduke’s Invasion of Missouri

- Chapter 11. The Battle of Springfield

- Chapter 12. The Second Half of the War

- Chapter 13. The Aftermath of the War

- Chapter 14. Postwar Commemoration

- Bibliography

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Civil War Springfield by Larry Wood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de la guerre de Sécession. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.