- 131 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

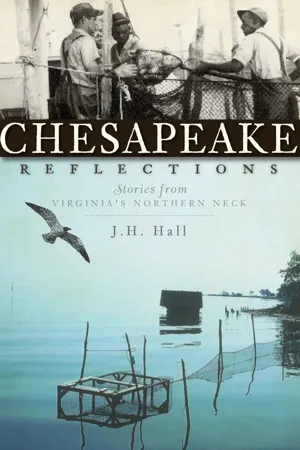

One man celebrates and laments his family's connection to a disappearing paradise of natural wildlife and beauty on the shores of Chesapeake Bay.

Between the Indian and Dividing Creeks, near the mouth of the Rappahannock River in Virginia's Chesapeake Bay, sits a parcel of land called Bluff Point. Like most bay-front villages, the bountiful resources and majestic landscape of this area that once sustained watermen and sportsmen alike have been depleted as over-harvesting, poaching, pollution and continued development have taken their toll, threatening the very legacy of its people.

J. H. Hall's family first settled on this land shortly after the Civil War, where they maintained a tradition of farming, fishing and crabbing throughout the twentieth century. Hall's words flow as splendidly as the tides in this collection of personal reminisces and local and natural history honoring the lives of the watermen before him and the uncertainty surrounding those today.

Between the Indian and Dividing Creeks, near the mouth of the Rappahannock River in Virginia's Chesapeake Bay, sits a parcel of land called Bluff Point. Like most bay-front villages, the bountiful resources and majestic landscape of this area that once sustained watermen and sportsmen alike have been depleted as over-harvesting, poaching, pollution and continued development have taken their toll, threatening the very legacy of its people.

J. H. Hall's family first settled on this land shortly after the Civil War, where they maintained a tradition of farming, fishing and crabbing throughout the twentieth century. Hall's words flow as splendidly as the tides in this collection of personal reminisces and local and natural history honoring the lives of the watermen before him and the uncertainty surrounding those today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Chesapeake Reflections by J H Hall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PARADISE

At first light, Roy Simon was already up and on his way to his uncle’s house. If you were going to be a commercial fisherman, you had to get up early. You couldn’t lie around in bed all day like some people he knew.

The dirt road passed like a valley between two fields of corn. The stalks, some twice as tall as Roy, rustled in the light breeze. A quail whistled from the hedgerow. Roy whistled back, off-key, silencing the quail. “Awright,” Roy said. “If that’s how you’re going to be, I’ll see you in November.” His family would be back for Thanksgiving, and he and his uncle, Lester Harmon, would hunt birds together. Then at Christmas they would hunt ducks and geese. His father did not hunt or fish. He sold real estate and played golf.

Last night there had been an argument about golf. It was a short argument. Roy didn’t even like his father to bring his golf clubs to the country, but his father liked to practice sand-irons on the bayshore. The bayshore was a sanctuary, wild, with no houses. You could walk for two miles and see nothing but washed-up bottles, crab pot buoys and arrowheads. Once Roy had his picture in the Richmond Times with his arrowhead collection. He had tried to teach his father the names of the arrowheads—Halifax, Lamoka, Morrow Mountain—but it was hopeless. How could you teach something like that to a person who saw the bayshore as a big sand trap?

Lester lived alone on a narrow peninsula in a white frame house flanked by a pair of silver maples, whose limbs overhung the tin roof like protective arms. Roy stood in the yard and looked around at the cove and the crab floats; at Lester’s dock and big boat, the Mary V; at the white skiffs lying still in the water; and, to the east, at the creek and the beach and beyond the beach out into the Bay, which seemed vast and endless. “This place is paradise,” Roy said. “Why can’t he see it?” Sometimes his father would walk around the place, using his hands as a viewfinder. Roy knew exactly what he was doing. He was measuring house lots.

Roy heard a noise, turned and saw his father’s Buick station wagon pull into the yard. His father, Rud, was a large man with pinkish skin that would not tan and thinning silvery hair. He walked over to Roy. “I’m still not playing golf,” Roy said.

“You made that clear last night,” his father said. His father looked around, his eyes adjusting to the dim light. “So,” he said, “I thought, if you didn’t mind, and if it was all right with Lester, I would go out fishing with you. With Lester.”

“Oh,” Roy said.

“If you don’t think Lester would mind.”

“No. No, I’m sure he wouldn’t mind.”

They walked down to the dock, where Lester and his hired man, Otha, were readying the boat. Roy’s father was wearing white Bermuda shorts, a baby blue golf shirt and a pair of dark glasses dangling from his neck. Roy was wearing blue jeans, a T-shirt and tennis shoes. No dark glasses for Roy. Dark glasses were for city people, “come-hithers.” Watermen, like Lester, didn’t wear dark glasses; they wore baseball caps, and they squinted. Squinting was what caused the creases in the corners of their eyes that turned white when their faces relaxed. Lester’s face was lined and furrowed like soft leather, like Roy’s baseball glove. Otha’s face was black and round as a catcher’s mitt. Otha had worked for Lester longer than Roy had been alive.

Otha was loading boxes and barrels into the bow of the Mary V when Roy and his father walked out onto the dock. Lester was tinkering with the engine. They were both wearing olive green oilskins and baseball caps. “Uh oh, Cap’n,” Otha said when he saw who was coming, “looks like we got a full crew today.”

Lester looked up from the engine box. “Darned if we don’t.”

“I won’t be in your way, will I?” Rud asked.

“No, indeed,” Lester said. “Glad to have you. Can’t pay much, though.”

Roy laughed.

“He’s telling the truth now,” Otha said. “He don’t pay anybody much.”

“That’s the trouble with people these days,” Lester said. “They all want to make big money, but they don’t want to work.” Lester hit the ignition, and Otha’s comeback was lost in the roar of the engine. Roy laughed anyway. He was sure that whatever Otha said would have been funny. He thought Otha and Lester were two of the most comical men he had ever known. He thought they should have been on TV.

“They’re right funny, aren’t they?” Roy said to his father. He had to shout to be heard over the engine.

His father nodded and patted his shirt pocket. “I wish I’d thought to bring my Dramamine,” he said.

“What?”

“I wish I’d brought my Dramamine.”

Roy shook his head. “Calm as it is, you won’t need it today.”

Lester throttled back, shifted gears and eased the boat out into the channel. “It’s a Gray Marine,” Roy said. “First V-8 on the creek.”

“Is that a fact?” Rud said.

Roy lay on top of the small forward cabin and watched the sunrise. The Bay was as smooth as thermometer mercury, motionless except for the groundswells that moved through the water like a large animal under a blanket. The slow rolling motion almost rocked Roy to sleep, but his father sat rigidly upright, his hands fastened to the rim of the deck like claws. With every swell, he pushed up as if riding a horse. Roy reached over and touched his father’s arm. “Just relax,” he said. “Don’t fight it.”

“Right,” Rud said.

Roy wished his father hadn’t come. These things never worked. Once he had tried to show his father how to read and break peeler crabs, and his father somehow managed to get both his thumbs crushed. Roy still wasn’t sure exactly how it happened. One minute his father had the crab safely by the back fins; the next minute the crab had him by the thumbs. His father howled in pain, and Roy—like a fool, he knew, but it was before he realized how much it hurt—laughed. He hadn’t meant to, but it all happened so fast it was like magic, like sleight of hand. Another time he had tried to show his father how to shuck an oyster and the oyster ended up in small pieces, with the oyster knife stuck into the palm of his father’s hand. At least that time Roy didn’t laugh.

Lester and Otha tied the big boat to the pound net stakes, climbed over into the skiff they’d towed out and paddled around to the top of the net. Lester leaned over, pulled up a line and lashed it to a stake. “That’s the anchor line to the pound net,” Roy said. “And that one holds the funnel between the false pound and the pound open.”

His father nodded and swallowed.

Lester shoved the top line of a loose section of net underwater with the oar and in the same motion slid the skiff over the net. “Did you see that?” Roy said, but his father was looking the other way.

Lester and Otha paddled to the far side of the pound and worked a slack piece of net up so that all the fish were between them and the big boat, but still deep and out of sight. As they pulled themselves toward the Mary V, Roy moved to the edge of the deck. “This is the good part,” he said. “This is where it gets exciting.”

“I think I’ll go sit up there for a while,” his father said, pointing to the very bow.

“What?”

“I think I’ll feel better if I can see the land.”

“But you’ll miss the best part.”

“I’m sorry. It can’t be helped.” His father went and sat on the bow and stared inland at the beach and the trees and the fields. Roy watched him for a moment and then turned away and watched the fishing.

As Lester and Otha tightened the net, the trapped fish became increasingly frantic. Small fish drove their noses through the mesh. Larger fish shimmied up the sides of the net. Fish leaped into the air. They churned the water to a froth.

“A few spot,” Lester said as he and Otha slacked the net to settle the fish.

“How many boxes you think you got?” Roy asked.

“Hard to tell,” Lester said. “We got a few though.”

Roy shook his head. He’d bet anything that Lester had those fish sorted, weighed and sold already and that he knew the price to the nearest dollar.

Lester looked up from the fish for a moment, removed his cap and wiped his forehead with his arm. “Is your father all right?”

“Yeah, he’s fine,” Roy said. “He just wanted to see the farm from another angle. You know how these real estate people are.” Roy was glad when Lester started bailing fish, because Roy did not want to talk about his father. The less said about his father the better. Roy did not want to be the son of someone who got seasick.

While Otha bailed the undersized fish and sea nettles overboard, Lester bailed the good fish into the Mary V. The first netfuls of fish made a hollow drumming sound against the floorboards. Then, as fish piled on fish, there was a flat drumming sound, and a fine mist of fish slime and seawater rose a foot or so above the fish. Then the drumming quieted and the mist disappeared as the fish settled, their gills flared, colors darkened and their markings became more distinct: the deep gold of the spot; the dark green along the backs of the bluefish that turned silver along the belly; the mottled brown and silver of the gray trout and croaker; the sharp black spots of the speckled trout; the mother-of-pearl sides of the butterfish. But they weren’t all beautiful. The oyster toad’s head looked like it had been stepped on; its lower jaw jutted out like a drawer full of teeth. Its brown, slimy skin bristled with spines. The swell-toads were more foolish looking than ugly, with their headlight eyes and rabbit teeth and habit of inflating themselves with air so that in the boat they’d lie around like volleyballs. If space became a problem, a pocket knife was the solution.

When Lester finished bailing fish, he climbed back into the big boat and rolled a barrel on its edge over to the gunnel. When he stood the barrel upright, fish squirted out from under it like spit watermelon seeds. He started sorting the crabs that Otha handed up one netful at a time. “Are you sure your father’s all right?”

“Oh, yeah, he’s fine,” Roy said.

“I think if it was my father, I might want to go and check on him.”

Roy did not want to check on his father, but since Lester had asked, what could he do? Lester was the captain of that boat, and the captain had absolute authority. So Roy said, “All right,” and slowly, reluctantly, moved up and sat beside his father.

“So how you doing?” Roy asked.

His father shrugged noncommittally. His skin was the color of seawater.

“No better, huh?”

His father shook his head and swallowed.

“You’re not going to get sick, are you?”

His father swallowed again.

“Damn—I mean darn. I hope you don’t get sick. You think you can hold it ’til we get back?”

His father sighed.

“The other nets are hung up drying,” Roy said. “This is the only net we’re going to fish today. Thirty, forty minutes at the most and we’ll be back on shore.”

“Thank God,” his father said through a narrow slit.

“That bad, huh? I’ll tell you what, we’ll make a deal. If you don’t get sick, when we get back, we’ll go play golf. I mean it. As soon as we get back, we’ll go over to the bayshore. Okay?”

His father looked at him, his eyes glazed and weary. “Please leave me alone,” he said. Then his mouth clamped shut like an oyster.

“Okay, okay, I’m leaving. I wouldn’t have bothered you in the first place except Lester made me.” He patted his father on the leg. “I hope you feel better.”

Roy scooted back to where he’d been sitting. Lester shook a large jimmy crab off the end of his heavy rubber glove into a bushel basket and then dumped the sooks and smaller males, all connected by their claws, into the barrel. “So how’s your father doing?” Lester asked.

“Well,” Roy said. “I guess he is a little under the weather. We’ve all had a touch of the flu. He had it worse’n any of us. I thought he was over it, but I guess not. He’ll be all right, though. He’ll shake it off. I’m telling you, these Simons are tough. They’re almost as tough as Harmons.”

Then his father leaned out over the bow as far as he could and vomited profusely for several minutes.

“Damn flu bug,” Roy said. “I knew he shouldn’t have come...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Bluff Point, the Big Picture

- Uncle Harry’s Funeral

- Paradise

- Croakers, Toads and Rock

- When the World Was Mine Oyster

- Otha’s Ghost

- A Brief History of Quail Hunting on Bluff Point

- Catch-and-Release Gill Netting

- Hunting versus Poaching

- Close to Nature

- Arrowheads

- Pollution Nostalgia

- Billy Haynie: A Hopeful Future

- Sources