![]()

Mrs. Chadwick Was

No Lady

Mrs. Chadwick will be placed in a cell on the second tier of the prison. She will be entirely alone on the tier, which is set apart from the other prisoners. She gave her age as fifty-one years, said she was born in the United States, not specifying any state, and that she was married.

—Warden of New York’s infamous city jail, The Tombs

Cassie Chadwick might be called the most socially prominent Cleveland heiress who never lived. Her father, it was whispered by all the “right” people, was steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, one of the two wealthiest men of his day. Her mother was unknown, though she was presumed to be as irresistibly beautiful as a siren’s song since bachelor Carnegie’s morals were of the highest order in that Victorian society.

The peccadilloes of Cassie’s parents were a curiosity among the Cleveland elite, but being an illegitimate daughter brought disgrace only to the lower classes. The fact that she was the heiress to millions made Cassie as desirable in the city’s mansions, private clubs and salons as if she had been the product of Immaculate Conception.

There were other advantages to inherited wealth. Access to cash was never denied. Bankers took Mrs. Chadwick into their private offices and provided her with loans for any amount of money she desired. They were always gracious, always kind and always solicitous about her well-being, all the while charging her interest rates far in excess of what was normal. It was Carnegie money, they seemed to reason, sums beyond comprehension. Besides, Cassie was such a genteel lady that she did not argue over the outrageous charges. She understood that the bankers’ inappropriate behavior was the result of greed, and since she had no intention of ever repaying their loans, she knew she would not suffer at their hands.

Purveyors of upscale merchandise were more respectful of Cassie. They supplied her with the finest clothing, shoes, jewelry and accessories, always charging her a fair price for the quality items. The retailers only wanted a legitimately earned profit in order to ensure a long-term customer of such breeding. And even when payment was inexplicably delayed, there was little concern. Letting other customers know that one was helping to outfit the socially prominent Mrs. Chadwick was like a London merchant advertising that he was a purveyor of goods to the royal family. The price could be written off as advertising, and he would usually still come out ahead.

In addition to the things Cassie’s wealth permitted her to acquire, she benefited in the press, where even her harshest critics muted their comments. Writers seeking her favor conveyed the image of Mrs. Chadwick as someone of great beauty, her body as sculpted as that of a showgirl and her wit and wisdom lauded as though she had attended the finest of finishing schools before given the standard “spoiled rich girl” tour of the continent. It was not until years after her death that more accurate physical descriptions appeared.

Cassie had both a speech impediment and was partially deaf. Her clothing was custom tailored, but her taste in style, material and color were enough outside the mainstream for her to be considered dumpy at best. A century after her death, in 1909, David J. Krajicek, a writer for the New York Daily News, described her as having been “corpulent and stern, she had a tight, unsmiling mouth, somber dark eyes and a nest of dull, dyed brown hair.”

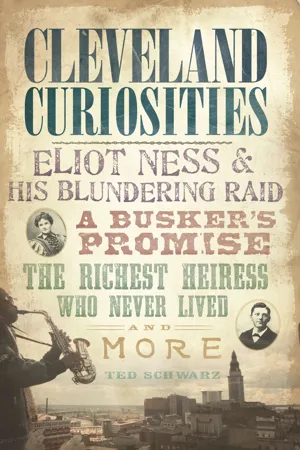

Portrait of Cassie Chadwick in 1904. Courtesy of Cleveland Public Library Photograph Collection.

The two features that did not work against Cassie’s appearance were her eyes and her demeanor. She would look directly at the person with whom she was speaking, her focus on them so intense that they felt themselves the most important person in her very privileged world. At the same time, there was a gentleness about her that made almost unthinkable the idea of questioning her personal history before she arrived in Cleveland. Cassie Chadwick was simply accepted for who she said she was, a lady fortunate enough to have been the “love child” of Andrew Carnegie and the adored wife of highly successful Cleveland physician Dr. Leroy S. Chadwick. No one, not even her husband, knew that Cassie Chadwick, arguably the most fascinating woman in Cleveland, did not exist.

ELIZABETH BIGLEY

In October 1857, Elizabeth Bigley was born to Daniel and Mary Ann Bigley of Eastwood, Ontario, Canada. The small-town couple had eight children in all, and keeping the family fed and clothed took more than one job. Daniel and his wife farmed a small plot of land in addition to his working as the boss of a railroad section gang.

Elizabeth Bigley was a reader and a dreamer as a child. Hers was not a life of hunger and privation as sometimes motivates those born into poor circumstances. Her family did as well as most of their neighbors and better than some. She had enough to eat, and the family could afford such luxuries as reading material, which Elizabeth devoured, always searching for stories about successful women in any endeavor.

Other children with similar interests might have considered opening a business, perhaps in one of the larger Canadian cities. Elizabeth seemed to have thought only about how to become a con artist, ensuring personal success through ill-gotten gains.

It was forgery that first intrigued Elizabeth Bigley. She learned about checks and how a bank would exchange them for real money if they were filled out correctly. More important, it was the banker’s perception of the client that determined what funds would be made available, not a careful scrutiny and cross-check of a potential customer’s true financial history. A man or woman who appeared to be well off but was impoverished would get a loan when someone who was wealthy but poorly dressed would not.

Elizabeth began practicing writing other people’s signatures, though when exactly she first attempted to pass a forged document is not known. Some reporters, writing after her death, suggested that she might have tried to pass a bad check for as much as $250 when she was thirteen years old. The stories, appearing in enough sources to possibly have been true, had her writing a letter stating that an uncle had died and she would be receiving a small sum of money. The forged notification of inheritance was good enough for an area bank to allow her to have checks for spending the money in advance of its arrival. The checks Elizabeth passed were genuine, the amounts nonexistent. She was arrested in 1870, told not to commit any more crimes and released. No one thought they could get a conviction against a thirteen-year-old girl.

Other sources say that the first scam came two years later, when Elizabeth was fifteen, and all the money came from selling a diamond ring she acquired from a neighboring farmer while she was still living at home.

The neighbor, a successful young man who had either purchased his land or inherited it from his family, fell in love with the teenage Elizabeth. She made it clear that she was a proper young lady, unwilling to go to bed with him until they were engaged.

Blinded by adoration, the farm youth mortgaged the land, bought Elizabeth a diamond ring and was promptly thanked as he desired. Then she returned to practicing forgery.

Elizabeth’s first arrest came the year after her “engagement.” One story says that she had been buying numerous personal items on credit from a local merchant, who eventually expected payment.

Another story had Cassie swindling several merchants, and when they became too demanding, she tried to cover her debts with a forged check for $5,000, an unimaginably large sum for a sixteen-year-old. Whichever story is true, and both may have been factual, the $5,000 forgery led to her arrest and subsequent acquittal on the grounds that she was temporarily insane.

It was when Elizabeth turned eighteen that she created the scam that would become the model she eventually perfected in Cleveland. Again acting with the knowledge that bankers were most amenable to providing large sums of money to men and women who did not need it, she became an heiress for the first time.

Elizabeth began the scam as she thought it might unfold in real life. First, there had to be a lawyer involved because a lawyer seemed to always be the person who handled wills and estates. He would also need to be from a large city and have been in the employ of a philanthropist.

Quality letterhead was obtained, and using the fictitious name and address of a London, Ontario attorney, Elizabeth notified herself that a philanthropist had died and left her an inheritance of $15,000. The letter looked official, and the amount was so large that it was presumed real.

Next, Elizabeth needed to present herself to the community in a proper manner so she could spend the money she had “inherited.” Toward this end, she had a printer prepare business cards that were much like the calling cards of the wealthy and social elite. Hers read:

Miss Bigley

Heiress to $15,000

The scam was a simple one that took advantage of retail practices of the day. She would enter a shop, choose an expensive item to purchase and then write a check for a sum that exceeded the purchase price. Sometimes the merchants were happy to give her the cash difference between the cost of the item and the amount of the check, a crude version of a debit card transaction. Sometimes the merchant balked at the idea of removing so much money from his business when it would be at least twenty-four hours before he could begin having his bank process the check. Some questioned whether the young woman, who was said to appear even more youthful than her eighteen years, truly had enough money to cover the cost of the object. It was then that Elizabeth proudly handed the merchant her “business card.”

The business card apparently worked every time. Why would the young woman have a card announcing herself to be an heiress if it was not true?

It is not known how long the scam could have continued had Elizabeth not became lazy. She should have gone to as many stores as possible in the course of a normal business day and then moved on to another city. Instead, she took a hotel room, let merchants know where she was staying and remained in London longer than the time it took for the checks to start to bounce.

The merchants immediately alerted the police, who, on Monday morning, raced to the hotel on the off chance that the “heiress” would still be in her room. She was, having packed her suitcases but not yet having checked out. She was promptly put under arrest, taken to the police station and presented to a group of merchants who had gathered to regain their money and property from the young thief.

(The early years of Elizabeth Bigley’s life are presented here as accurately as possible. The problem is that she was committing her first crimes in Canada when her skills were still being developed, and there was little coverage of her arrests. Adding to this is the fact that seemingly reliable sources for facts can be contradictory. Was she born in 1857 or 1859? Both dates have been noted, though it is presumed that 1857 is correct since all the reports of her death in 1907 state that she was fifty years old. It is only after she left Canada for Ohio that the stories become consistent.)

Elizabeth’s acting skills were far better than her forgeries at the time. She knew her appearance was odd, much younger than her years, so she took advantage of it. She scrunched her body, lowered her head and made herself look like a frightened, naïvely innocent little girl, not a scheming con artist.

The trick worked. The merchants decided to write off their losses rather than putting the obviously contrite child through further discomfort.

It was obvious that Elizabeth needed to work on her art. She had the heart and soul of a great con artist but her skills were still rudimentary. She returned to the family farm (no mention of any further relation with her neighbor has been found) and spent the next four years planning her future.

Elizabeth was twenty-two years old when she journeyed to Toronto. She dressed in her best clothing and brought with her a bank check of her own creation, a check that was for a substantial amount of money she would be transferring into a Toronto bank.

The fact that Elizabeth had no money and the check was a forgery did not matter. The check was duly deposited, and she felt herself free to spend the nonexistent funds while the deposited check was being cleared.

The big city of Toronto had financial institutions and businesses that moved faster than the other locations where Elizabeth had engaged in her scams. She spent the day she deposited the check going from business to business, buying whatever she desired. She took the merchandise to her hotel room, went to bed and discovered the police waiting for her first thing the following morning.

This time, there would be no escaping the law. This time, she found herself in court.

Elizabeth understood that appearance was everything. The fact that she looked like a small child the last time she was arrested gave her the impetus to try an insanity defense. While the prosecution presented the criminal case, Elizabeth stared off into space, laughed inappropriately, rolled her eyes, made odd sounds and generally presented the image of someone deranged.

The elaborate check-forging scheme had been done when Elizabeth was temporarily insane, the judge ruled. She would not go to jail. Instead, she would return to the farm.

Daniel and Mary Ann Bigley had had enough of their daughter’s crimes. Another daughter, Alice, had married Bill York, a carpenter from Cleveland, Ohio, and moved with her new husband to his hometown. Elizabeth soon followed, knowing her sister would help her resettle.

Elizabeth had no intention of imposing on her sister. She would stay in the newlyweds’ home on Franklin Avenue only long enough to make adequate financial arrangements for a new business venture.

Alice and Bill may have thought Elizabeth was going to seek employment. Instead, she roamed their house, taking stock of all furnishings, from the chairs they sat on to the paintings on the wall. She determined their approximate value and then arranged for a bank loan using the furnishings as collateral.

Again, this is a period when the facts are uncertain. Some reports say that Bill learned of his sister-in-law’s actions and threw her out of his house. Others say that this was one time when she knew to move out before matters got out of control. Either way, she kept the cash from the York furniture and used it to establish herself as the clairvoyant Madame Lydia DeVere.

She is also believed to have spent a short period of time moving from boardinghouse to boardinghouse, staying in each only long enough to get a bank loan for the home’s furnishing as she had done with the Yorks. Whatever the case, she eventually settled in a home at 149 Garden Street owned by a Mrs. Brown. Madame DeVere had the entire first floor, allowing her a place to stay and to conduct business.

LYDIA DEVERE

Lydia DeVere had gone as far as she could on her own. She had a thriving business, money saved and money being spent for her services, and she probably could have continued with such modest success for many years to come. However, it was not enough. Lydia decided to become rich the old-fashioned way—through seduction.

The widow DeVere did not lack for suitors in those early months in Cleveland, though what may have drawn them to her side is uncertain. She had no interest in marriage for the sake of something as simperingly immature as love. Marriage was a serious commitment, and the man she chose had better have income equal to that seriousness.

Lydia did not realize that her determination to marry a man of means was easily matched by her creditors’ determination to watch her business until they felt they could finally collect what they were owed. They were discrete, however, not letting anyone know they had observed the first successful swain since the neighboring farmer was gifted with her virginity.

Dr. Wallace S. Springsteen was a young Cleveland physician whose home was just down the street from the clairvoyant, at 3 Garden Street. He was new to his practice yet already had a reputation that made him of interest to the community. As a result, although the couple married in front of a justice of the peace on November 21, 1882, the Plain Dealer, one of the local newspapers, sent a photographer to record the event.

The newspaper story was read avidly by any number of merchants, as well as Lydia’s sister, all of whom realized that Dr. Springsteen could be the source of their finally being repaid. Eleven day...