- 131 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

From the end of the Great War to the final years of the 1950s, Kansas Citians lived in a manner worthy of a place called Paris of the Plains. The title did more than nod to the perfumed ladies who shopped at Harzfeld's Parisian or the one-thousand-foot television antenna nicknamed the "Eye-full Tower." It spoke to the character of a town that worked for Boss Tom and danced for Count Basie but transcended both the Pendergast era and the Jazz Age. Author John Simonson introduces readers to a town of vaudeville shows and screened-in porches, where fleets of cream-and-black streetcars passed beneath a canopy of elms. This is a history that smells equally of lilacs and stockyards and bursts with the clamor of gunshots, radio baseball and the distant whistle of a night train.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Paris of the Plains by John Simonson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

1910s–1920s

A NEW PHASE OF LIFE

The November morning was brisk, bright and promising, so I went underground.

It was not a protest against beautiful autumn days but a long-overdue, first visit to the National World War I Museum—a sleek twenty-first-century bunker beneath the 1920s-era Liberty Memorial.

Therein I saw spiked helmets, colorful tunics and hand grenades of many nations. I stood in a scale-model shell crater amid recreated sounds of battle. I read maps, timelines and charts of numbers upon numbers. I watched short films with ominous soundtracks. It was a blend of antique and high tech working hard to distill and animate years of events that snuffed an old world and birthed a new one. Even spread out over three hours, it was pretty overwhelming.

So I rode the elevator up and back, about ninety years, to the observation deck of the Liberty Memorial.

When the war ended in the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, people here had already been talking for two days about the Kansas City Journal’s idea.

“The most practical and most happy suggestion for perpetuating the glorious achievements of the Kansas City, and Missouri and Kansas soldiers,” the newspaper called it. “Erect a Victory monument in the station plaza.”

Detail of a frieze by Edmond Amateis on the north wall of Liberty Memorial. Courtesy of the author.

Civic leaders reacted: “A splendid idea indeed.” “A glorious way for the people of Kansas City to express their appreciation of the soldier boys.” “Let’s not talk about it, but go right ahead and provide the monument.” “What a grand thing it would be to do.”

And there was another thread of thought: “It would beautify the city,” said the Journal.

“The victory arch at dawn, the victory arch at noontime, in winter, in spring, in the fall, the victory arch at sundown, at midnight—what a pleasure for Kansas City and a privilege to gaze at its ever-changing beauty.”

The architect of the city boulevard system took it another step. It was time to move beyond a preoccupation with commerce—it was time for art.

“I believe the memorial is but the beginning of further effort along the line of great civic enterprises,” said George Kessler. “We are beginning to learn that there is another phase of life besides that of accumulating.”

Funds for the monument came from private donations. The entire $2.5 million was raised in ten days.

The thing that now loops in my memory of the war museum is the audio alcove: a glassed-in cone of silence with softly colored lights and a sound system that plays snippets of old speeches, music and literature. It delivered that old world to me more immediately than any timeline or ersatz shell hole.

A keypad touch brought the voices of the kaiser and President Wilson; songs like “How ‘Ya Gonna Keep ’Em Down on the Farm (After They’ve Seen Paree?)”; and excerpts from A Farewell to Arms and The Great Gatsby. There was also “In Flanders’ Fields,” the poem written by Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, a Canadian who never it made it home from the war; I played that one twice.

It was a poem my schoolgirl mother memorized in the 1940s, when schoolchildren did such things. November 11 was called Armistice Day and veterans of that war—some missing an arm or a leg—sold carnations on street corners. The other day on the telephone, Mom proved she hadn’t forgotten the verse that begins: “In Flanders Fields the poppies blow / Between the crosses row on row.”

The November sun was shining up on the Liberty Memorial observation deck. With its commanding view of the city, this has long been an island of peace and a quiet place to reflect about lots of things: about the ironies of a war to end all wars; the poetry in thousands of poppies at the museum entrance and the lighted “torch” atop the memorial’s two-hundred-foot tower; the fact that fewer travelers now first see this place from Union Station than from speeding cars on the section of Interstate 35 that slices through downtown; or the enduring, ever-changing beauty of the monument. As a war memorial, it is a source of civic pride and a portal to a younger city— awakening to a new phase of life.

GONE WEST

Sixteen hundred miles west of Union Station in the Los Angeles suburb of Monrovia, just off the Foothills Freeway, past the Wal-Mart and the Home Depot, inside the leafy and spacious confines of Live Oak Cemetery lies a headstone that reads: “Fritz E. Peterson, 1892–1931, 110 Engineers 35 Div.”

It marks the final resting place for an Army veteran who returned home to Kansas City from the Great War and heard California calling him to become a chicken rancher.

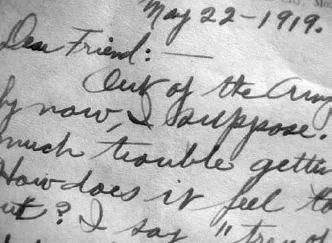

Fritz Peterson’s postcard. Courtesy of the author.

The 110th Engineers were maintenance workers. They dug trenches, built shelters, cleared battlefields and did other manual labor for the 35th Division of the American Expeditionary Forces in France during the summer and fall of 1918.

The Thirty-fifth Division saw only five days of action, in late September, in the Argonne Forest. In five days, the division advanced more than six miles, captured more than seven hundred Germans and suffered more than six thousand casualties, including more than a thousand dead. There’s a story about a group of engineers working in the field who, attacked by Germans, fought with picks and shovels until their armed comrades arrived.

The 110th seems a natural place for Fritz Peterson to have landed after being drafted in 1917. His father was a maintenance engineer for the Kansas State School for the Blind in Kansas City, Kansas.

The Great War had its own language. Tank, camouflage, dogfight, dud and no man’s land are terms that survive. Less remembered, perhaps, are to swing the lead, which means to malinger; to go west, which means to die; and some slang terms based on mispronunciations of French words, such as toot sweet from “tout de suite” and tray beans from “tres bien,” To American doughboys, a Fritz was a German soldier. That must have made life interesting for Fritz Peterson.

They came home in late April and early May 1919, those men of the Thirty-fifth Division, most from Missouri and Kansas. Full trains pulled into Union Station, sometimes with casualties and many missing arms or legs, in which case they would stop for Red Cross ladies to board with food and cigarettes, and then they would continue to convalescent hospitals somewhere. More often, the trains unloaded soldiers who would parade down Main Street to celebrate at downtown hotels, and then they would head back to the station for the last few miles to Camp Funston and a discharge.

A few weeks later, one of them wrote a message on a picture postcard of Union Station and addressed it to Chicago:

Dear Friend,

Out of the Army and home by now, I suppose. Have much trouble getting out? How does it feel to be out? I say “tray of beans.” Ha! Ha! I may go west.

Best regards,

Fritz E. Peterson

OLD ROSE AND WHITE

It’s one of those industrial landscapes—in this case, a concrete-and-razor-wire parking lot—that has swallowed whole blocks between the Crossroads and Historic Jazz Districts. No street signs exist here, but this used to be the intersection of Nineteenth and Tracy.

The area is so bleak that it’s difficult to imagine anyone using the corner’s bus stop, which is a vestige of the streetcars that stopped in front of the school that once stood here. On maps, it was sometimes identified as “Lincoln High School (Colored).”

Lincoln High was a predecessor of today’s Lincoln Prep Academy, which sits on the hill at Twenty-first and Woodland. Actually, the old Lincoln curriculum was preparatory, as well. Students took classes in science, history and English literature. In the vocational-training department, they learned sewing, automobile repair, carpentry and bricklaying. Lincoln was well-known for music education.

Alumni included Walter Page, who played the upright string bass, later founded the Blue Devils and eventually became part of the famed rhythm section in Count Basie’s Orchestra; and Charlie Parker, who used an alto saxophone to change the future of jazz.

Sidewalk detail at the corner Nineteenth and Tracy. Courtesy of the author.

The class of 1920 included Maceo Birch, who became a local entertainment promoter, later the road manager for the Basie Orchestra and eventually the head of the Negro band department at MCA records.

The summer before Maceo’s senior year had been especially bad for lynchings in America; more than seventy were reported. During the school year, a black man was shot to death by a mob 140 miles east of Lincoln High in a small Missouri town. Another was hanged by a mob 120 miles south in a small Kansas town.

Here in Kansas City that year, children at an all-white elementary school put on a play, The Pied Piper of Hamelin. The play had a black character whose lines included: “But chile! Yo’ should hab seen dem rats when dat Massa Pied Piper come in dis ar town. Da’ followed dat man just like a lot o’ white trash after a hunk o’ lasses taffy.”

At an all-white high school, the play was a comedy titled Alabama. A reviewer remarked of one character: “No one would ever have thought that George Pratt could make such a good ‘nigger’ as Decatur until he saw ’Alabama.’ George’s wobbly legs and ‘nigger talk’ brought much laughter from the audience.”

At Lincoln, seniors reported their life ambitions to the school yearbook. Maceo Birch said he wanted “to own and operate a sporting goods store.” For others it was to be a nurse; a milliner; an expert typist; an athlete second to none; a great businessman; or a first-class contractor, cornetist, cook, stenographer or dentist. They also aspired to be a bantamweight champion prizefighter, chief cook for Fred Harvey, cartoonist for the New York Tribune, leading soprano in Tolson’s Jubilee Concert Company or president of Petty Business College. Others wanted to become a lawyer, oil magnate, drum major in a great band, vamp, old maid or Mrs. Miller. And some hoped to teach English at Wilberforce, travel with Bradford’s band, have a fancy art shop on Petticoat Lane, own a first-class garage on Vine Street or live as royal as a king.

Under the bus-stop sign at Nineteenth and Tracy lies an old suggestion: a remnant of sidewalk and some brick pavers, cracked and broken. In 1920, Lincoln High was a handsome brick building. It’s not known whether any member of the class of 1920, in his or her heart of hearts, ever imagined being sworn in as the president of the United States.

What is known is that the class colors were old rose and white; its flower was the sweet pea; and the class motto was Vestigia nulla retrorsum— no steps backward.

BLACKFACE AND A BLUE CHAIR

Down at the corner of Fourteenth and Main, where intensely bright lights turn night into day, the gray stone façade and celery-green dome of the new-old Mainstreet Theatre appear handsomely 1921, even as its marquee and innards are now brilliantly twenty-first century.

My favorite detail is the throwback sign—vertical lettering encircled by lights that rise like bubbles in a flute of champagne—which erases time, leaping over the shuttered years, over the Empire and RKO Missouri years to the period between the world wars.

The 1921 Mainstreet was the work of Rapp & Rapp architects of Chicago, who were responsible for theaters in more than twenty American cities, including the Paramount in New York and the Chicago in Chicago.

The Mainstreet Theater’s effervescent sign. Courtesy of the author.

Today, their Mainstreet facade is a shell for a state-of-the-art, six-screen movie complex.

The original theater was built by t...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. 1910s-1920s

- 2. 1930s

- 3. 1940s

- 4. 1950s

- Epilogue

- About the Author