eBook - ePub

Massacre of the Conestogas

On the Trail of the Paxton Boys in Lancaster County

- 131 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A gripping account of how a vigilante mob of Pennsylvania frontiersmen butchered a Native American tribe—and got away with it.

On two chilly December days in 1763, bands of armed men raged through camps of peaceful Conestoga Indians. They killed twenty Susquehannock women, children and men, effectively wiping out the tribe. These murderous rampages by Lancaster County's Paxton Boys were the tragic culmination of a gruesomely violent conflict between European settlers and native tribes.

The Paxton Boys then journeyed to Philadelphia, not to evade the law but to confront it. They openly threatened to commit more of the same violence if their demands were not met. In Massacre at the Conestogas, Lancaster journalist Jack Brubaker gives a blow-by-blow account of the massacres, examines their aftermath, and investigates how the Paxton Boys got away with murder.

On two chilly December days in 1763, bands of armed men raged through camps of peaceful Conestoga Indians. They killed twenty Susquehannock women, children and men, effectively wiping out the tribe. These murderous rampages by Lancaster County's Paxton Boys were the tragic culmination of a gruesomely violent conflict between European settlers and native tribes.

The Paxton Boys then journeyed to Philadelphia, not to evade the law but to confront it. They openly threatened to commit more of the same violence if their demands were not met. In Massacre at the Conestogas, Lancaster journalist Jack Brubaker gives a blow-by-blow account of the massacres, examines their aftermath, and investigates how the Paxton Boys got away with murder.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Massacre of the Conestogas by Jack Brubaker in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781614232759Subtopic

Early American HistoryPART 1

Telling the Story

CHAPTER 1

“Drive the Heathen Out of the Land”

The horses stepped gingerly along the rocky, snow-covered path. The long-coated riders gripped their pommels and rode with ease, guiding the horses as if they were extensions of their bodies. They wore no uniforms but carried the calling cards of war: flintlocks, tomahawks, knives. They looked to the path ahead, only occasionally glancing into the trees and underbrush or, through an opening, to the wide Susquehanna.

Early that morning, December 13, 1763, more than fifty of these riders had assembled near John Harris’s Ferry, at a place called Paxton in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.1 Most were Scots-Irish Presbyterians, and many were members of the Paxton Rangers, a militia unit formed to protect Paxton and its neighboring townships from marauding Indians.

The riders had traveled downriver from Paxton, adding recruits as they passed through the largely Scots-Irish townships of Derry and Donegal. They had ridden close by the Susquehanna on the Paxtang Path, past the turbulent froth at Conewago Falls and around the great resistant rock at Chickies. As a shrouded sun set, the Rangers rode down the ridge to John Wright’s Ferry, a small settlement at another important river crossing.2 Under threat of even wilder weather at the end of a remarkably cold year that had registered frosts in every season, they had traveled nearly thirty miles. It was time to rest.

The Rangers set off in small groups to find lodging. One gang of men, perhaps ruder than the rest, stayed in the home of a German Mennonite farmer. Late in the night, they tossed their host’s pewter on a stove and melted it down.

The militiamen slept lightly and rose before dawn. Snow was falling as they reassembled at the ferry and continued their journey downstream. As they rode, the men reviewed recent events. They cursed hostile Indians for murdering frontier settlers, some of them friends, in the small villages and on the farms to the north and west of Paxton. They thought about how pleasant the fertile land and abundant forests would be if only the hostiles would stop coming down the river to assault unsuspecting families.

In late August, unsettled by recent Indian depredations, some of the Rangers had decided to follow the enemy home. They had ridden north to the Susquehanna’s West Branch. There a group of Indians painted for war had surprised the militiamen, killing four and wounding six before disappearing into the woods. Demoralized by the ambush, the Rangers had decided to return to Paxton. Along the way, a small group that had become detached from the main body had run into three Indians returning home after trading at Bethlehem. The Indians had posed no threat, but the Rangers had shot them and returned to Paxton with their scalps—their only emblems of success.

Determined to find and fight hostile Indians, the Rangers in October again had ridden up the Susquehanna, this time along the North Branch. There they had found ten members of a Wyoming Valley settlement butchered. The Indians had roasted a woman. They had thrust awls through the eyes of the men. They had run spears and pitchforks through their bodies.

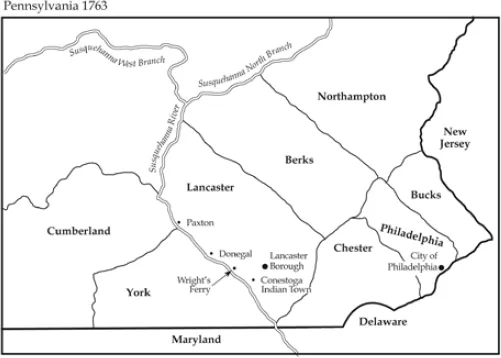

Map by Chris Emlet.

The Rangers again had returned home demoralized. They had little to show for two trips up the river but three scalps, four lost comrades and frightful images of the dead. These images remained fresh on the morning of Wednesday, December 14.

After the riders reached another river-resisting rock, named Turkey Hill after a wild flock, they cut inland along the next ravine carrying a run into the Susquehanna. They rode up the snow-filled ravine to level ground and headed due east toward the Indian village at Conestoga Town. The small cluster of log huts lay near a spring on rising ground some three miles from the river. The people sleeping in the village had no reason to believe that anyone meant to harm them.

For more than seven decades, the Conestogas had enjoyed the protection of Pennsylvania’s proprietary government. In 1701, William Penn, founder of the colony, had given the Indians three thousand acres in Manor Township. Sixteen years later, his sons reduced that tract to just over four hundred acres. The Conestogas felt relatively safe in a restricted region surrounded by sympathetic and pacifistic Mennonite and Quaker farmers. The government had appointed some of these neighbors as caretakers.

Map by Chris Emlet.

As time passed, the Conestogas adopted the customs of many of their neighbors and, increasingly, looked much like them. They abandoned native clothing. They built cabins of wood planks covered with bark. They hunted with imported guns and cooked in iron pots. Many converted to Christianity, at least superficially, after encounters with Catholic missionaries on journeys north to Iroquois country. Although called Conestogas, they actually represented several refugee Indian groups, including Senecas. Most spoke English.

The Conestogas were no longer free roamers. The Mennonites and Quakers had converted most of their old hunting territory into farmland, so the Indians tended vegetable gardens and fished in a nearby stream. They wove brooms and baskets to sell to their neighbors and on the market in the borough of Lancaster, eight miles to the east. When other strategies failed, they went begging, from farm to farm or to Pennsylvania’s government in Philadelphia.

Just two weeks before the Paxton Rangers arrived at their camp, the Conestogas petitioned the governor to “consider our distressed situation and grant our women and children some Cloathing to cover them this winter.” The Conestogas told the governor that “we are settled at this place by an Agreement of Peace and Amity established between your Grandfather and ours.” They said they had been loyal to Pennsylvania throughout the French and Indian War. And they said they remained loyal now, during the latter stages of a postwar “rebellion” directed by the powerful Indian leader Pontiac.

In 1763, only twenty people lived in Indian Town. On December 13, many had traveled several miles from home to peddle their woven wares. Fearing they would be caught outside in a heavy snow if they tried to return, most stayed overnight with a Mennonite farmer and at a nearby ironworks. So on the morning of December 14, only seven people slept in the village.

Many of these sleepers went by two names, their own and those their white neighbors had given them. They were Wa-a-shen, also called George Sock; Tee-Kau-ley, also known as Harry; Kannenquas, a middle-aged woman; Tea-wonsha-i-ong, or Sally, an older woman; her adopted child, Tong-quas, or Chrisly; and Ess-canesh, a young boy. The seventh Conestoga, Ess-canesh’s father, was Sheehays or Sohais, often called Old Sheehays, son of Connoodaghtoh. Of the seven, he has the most substantial biography.

Sheehays was so old, some said, that he had met with William Penn at the treaty session that had established Conestoga in 1701. Sheehays had been the tribe’s chief in the late 1750s and he had attended treaty sessions for decades. He had signed treaties the way he had signed the letter to the governor asking for winter clothing—by drawing a simple songbird on parchment. Settlers at Wright’s Ferry considered Sheehays a great friend. He felt the same about them. When someone had suggested that angry white men someday might come and murder him and his people, Sheehays had scoffed. “It is impossible,” he had said. “The English will wrap me in their matchcoat, and secure me from all danger.”

Indian Round Top rises near one of several eighteenth-century locations of Conestoga Indian Town. Photo by Christine Brubaker.

The Conestogas slept soundly, unsuspectingly in the continuing snowfall. As slender plumes of smoke rose from their fire-warmed huts, neither Old Sheehays, Ess-canesh nor any other sleeper was eager to beat the sunrise.

First light and the Paxton Rangers arrived together at Conestoga Town. The Rangers went about their business in a rush. They dismounted and fired their flintlocks at the Indian huts. They rushed inside and tomahawked the survivors. They scalped everyone. Then they looted the huts, lashed the booty to their saddles and set the buildings on fire.

The entire operation must have consumed only minutes. The Rangers remounted and, energized by the ease of their slaughter, rode rapidly from the village. It would be a long day’s ride back to Paxton. Worried wives would be waiting.

Indian Run flows through the Conestoga Indians’ four-hundred-acre tract in Manor Township. Photo by Christine Brubaker.

The victorious column had traveled only a couple of miles when it encountered Thomas Wright, one of the Conestogas’ Quaker neighbors. Suspecting the Rangers’ mission but not knowing it had been accomplished, Wright reminded the riders that Pennsylvania’s government protected the Conestogas. The Rangers replied that no government should protect Indians. “Joshua was ordained to drive the heathen out of the land,” they said. They asked, “Do you believe the scriptures?” Wright had no ready response, and the Rangers left the peace-professing Quaker standing stunned in the snow.

The killers stopped briefly at Wright’s Ferry. They again separated into small groups, one of which went knocking at the oak door of Robert Barber Jr., a Quaker leader in the riverside community. Removing overcoats encrusted with snow, five or six Rangers entered the settlement’s oldest brick house to warm themselves by one of its many fireplaces.

In the course of their conversation, the men asked Barber why he and his neighbors allowed Indians to live among them in uncertain times. Barber replied that the Conestogas were peaceful and inoffensive. So the Rangers asked what would happen if someone killed these Indians. Barber said he thought the killers would be as liable to punishment as if the Indians had been white men. The killers said they believed otherwise.

During this discussion, two of Barber’s sons walked outside. Tied to the saddles of the raiders’ horses they saw bloody tomahawks and young Chrisly’s toy gun. The boys had played with Chrisly—he had made bows and arrows for them; they had given him the gun—and the blood on the tomahawks alarmed them.

Soon after the Rangers rode away, Barber’s sons described what they had seen. Fearing the worst, Barber and other Wright’s Ferry Quakers rapidly rode to Indian Town. They were horrified to discover the burned bodies of the Indians lying amid the ruins of their huts.

Meanwhile, Chrisly had escaped. He alone had heard the Rangers approaching the village and had slipped away to run through the snow to inform Captain Thomas McKee.

McKee, another Conestoga neighbor and caretaker, listened to the story from the breathless boy with frozen feet. Then he sent a messenger to inform Lancaster County’s chief magistrate that the Conestogas and their village had been destroyed. Upon receiving the message, Edward Shippen III, chief of all Lancaster County judges, dispatched Matthias Slough, the county coroner, and John Hay, the county sheriff, to Indian Town. Their instructions: discover who had killed the Conestogas.

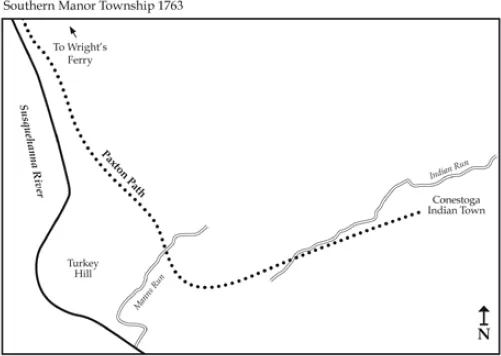

A memorial boulder designates the site of Conestoga Indian Town in Manor Township. Photo by the author.

Slough, Hay and thirteen other Lancaster residents dressed for white weather and rode out to Conestoga Town. They found the ravaged village, with all of the huts but one burned entirely to the ground. After poking through the charred remains, finding bodies scattered here and there in the ashes, the somber white men conferred. In the officious jargon of their “Coroners Inquisition,” they determined that the Indians had been slaughtered by “a person or persons to this Inquest unknown.” Then Slough contributed some money for burial, and the Barber party laid the bodies in the snow-covered ground.

When the remaining Conestogas returned to find a third of their number dead and their village destroyed, they wept and wondered what would become of them. Once again they sought shelter with Mennonite neighbors. There they were surprised and in part consoled to encounter Chrisly and his survivor’s story.

CHAPTER 2

“Some Hot Headed Ill Advised Persons”

Most Lancastrians learned about the massacre at Conestoga Town by Thursday, December 15. And by the next day, the provincial government at Philadelphia knew what had happened in the tiny Indian village near the Susquehanna some seventy miles to the west. In Lancaster and in Philadelphia, officials began to worry that the violent men who had murdered and burned the Conestogas might not stop with one assault.

The Paxton militiamen had ample reason to hate Indians. In 1757, at the outset of the French and Indian War, hostile Indians aligned with the French had raided Paxton, killing several inhabitants and burning their homes. The memory of that attack remained vivid among Paxtonians, even as assaults east of the Susquehanna diminished and the fighting shifted westward.

Conflict escalated again in the summer of 1763 as Pontiac, a charismatic Ottawa warrior in the Detroit area, led several groups of Indians in an armed protest against expanding British settlement following the French defeat. The violence overwhelmed forts and killed dozens of settlers as it rippled toward south-central Pennsylvania. For a time, Pontiac’s forces threatened to destabilize the entire frontier with the most concentrated Indian attacks the colonists had yet seen.

That summer and autumn, the Paxton Rangers guarded the northernmost section of Lancaster County. Renewed depredations in areas not far from their picket lines, along with their own frightful tours up the Susquehanna, reinforced what the Rangers had decided during the war: all Indians were enemies. They concluded, without substantial evidence, that Pennsylvania’s “friendly” Indians were monitoring white settlements and providing information to hostiles.

A view of Lancaster from the southwest, about 1800, shows a town that has sprawled east and west from its center since the massacre of 1763. The cupola of the county courthouse rises between church spires at center, and St. James Episcopal Church’s spire rises to the immediate right of the courthouse. The county prison is down West King Street hill, just over midway between the courthouse and the left edge of the drawing. Heritage Center of Lancaster County.

The Rangers were concerned about two groups: Lancaster County’s Conestogas and a band of Lenni Lenapes in Northampton County. The Lenapes had been converted by German Moravians in Bethlehem and were called Delawares or Moravian Indians in the white settlements. Many Rangers, however, called both the Lenapes and Conestogas spies.

John Elder commanded the Paxton Rangers a...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Part 1: Telling the Story

- Part 2: Retelling the Story

- Part 3: Killers and Abettors

- Part 4: Death and Reconciliation

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author