- 131 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Murder & Mayhem in Missouri

About this book

Desperadoes like Frank and Jesse James earned Missouri the nickname of the "Outlaw State" after the Civil War, and that reputation followed the region into the Prohibition era through the feverish criminal activity of Bonnie and Clyde, the Barkers and Charles "Pretty Boy" Floyd. Duck into the Slicker War of the 1840s, a vigilante movement that devolved into a lingering feud in which the two sides sometimes meted out whippings, called slickings, on each other. Or witness the Kansas City Massacre of 1933, a shootout between law enforcement officers and criminal gang members who were trying to free Frank Nash, a notorious gang leader being escorted to federal prison. Follow Larry Wood through the most shameful and savage portion of the Show-Me State's history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Murder & Mayhem in Missouri by Larry Wood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter Six

THE MURDER OF THE MEEKS FAMILY

The Most Horrible and Brutal Crime in the Annals of Linn or Sullivan County

About April 1, 1894, the prosecuting attorneys of Linn County and neighboring Sullivan County petitioned Missouri governor William J. Stone to release Gus Meeks from the state penitentiary in Jefferson City, where he was doing a two-year stint for grand larceny, so that he could testify against some “important criminals” with whom he had been associated in cattle stealing and other crimes in their counties. Assured that the thirty-one-year-old Meeks had been a mere “tool” under the influence of his co-conspirators, Stone signed the pardon on April 7, and Meeks was released the same day after serving only four months of his term. Unaware of the desperate character of Meeks’s associates, the governor had no way of knowing he had just signed the man’s death warrant.

Meeks’s main partners in crime were William P. Taylor and his brother George. The thirty-two-year-old Bill was a lawyer and a bank cashier at the People’s Exchange Bank of Browning, a small town in northern Linn County at the Sullivan County line. He had formerly been mayor of the town and had even served a term in the Missouri legislature. Thirty-year-old George Taylor had a farm about four miles southeast of Browning, near where the brothers had grown up. In 1891, Meeks and the Taylors had been arrested for forging a $2,000 check on the Browning Savings Bank, where Bill had worked at the time, and cashing it at Kirksville. After a change of venue from Adair County, they had been tried and convicted in Linn County Circuit Court and sentenced to five years in prison, but they had secured a new trial, which had not yet taken place. While awaiting the new trial, Bill was arrested and charged with arson for burning some buildings in Browning in an attempt to collect insurance, to destroy property owned by Browning Savings Bank owner Beverly Bolling (who had pursued the forgery charge against Taylor), and to try to frame Bolling for the crime. Next, Bill Taylor had induced Meeks to help him forge another check. Then, in September 1893, Taylor, Meeks, and two other men were arrested for stealing cattle from a farm near Cora, a small community about halfway between Browning and Milan, the Sullivan County seat. Taylor got his case continued, but Meeks pleaded guilty at the November term of court and was sentenced to two years in the penitentiary. Before being sent to Jefferson City, Meeks, who had lived across the street from the scene of the fire in Browning, was taken to the Linn County seat at Linneus to testify against Taylor in the arson case.

However, in the spring of 1894, the arson case and the forgery cases were still awaiting final disposition in Linn County, and Taylor’s trial on the cattle stealing charge in Sullivan County was docketed for the May term of circuit court. The prosecuting attorneys decided they needed Meeks to testify in order to secure convictions against Taylor. The request to have him pardoned in exchange for his testimony granted, Meeks was back home in Milan.

William P. Taylor sketch that appeared in newspapers shortly after the Meeks murders. From the Milan Standard.

On a Sunday night in mid-April, just days after Meeks arrived home, Bill and George Taylor showed up in Milan, where Meeks; his pregnant wife, Delora; and their three little daughters were staying with Gus’s mother, Martha Meeks. George came to the door of the house and asked Gus to come outside where Bill was, but Gus refused George’s repeated attempts to lure him outside. Finally, Bill and George came inside, and the three men had a conversation in the front room. Bill tried to talk Gus into leaving the area and not testifying against him, but Gus accused Bill of being the cause of all his troubles and told him it would take at least $1,000 to get him to leave.

During the next couple of weeks, Bill Taylor passed the Meeks house at least a time or two, but he apparently made no attempt to come in or talk to Gus. However, during early May, he and Gus exchanged several letters, and on May 8, the two men met in Cora. Meeks agreed, perhaps at this meeting, to leave the territory and not testify against Taylor in exchange for $800 and a wagon and team. On Thursday afternoon, May 10, Meeks received a final letter from Taylor telling him, “Be ready at 10 o’clock. Everything is right.”

On the night of the tenth, Bill and George Taylor drove a wagon and team, which belonged to their father, to Milan to get Meeks, arriving about 11:00 p.m. While Bill Taylor remained in the wagon, George came to the door and told Gus that everything was set. The original plan had called for Meeks to leave the territory alone and then send for his family after he got settled, but Delora mistrusted the Taylors and, thinking they would surely not harm Gus if his family were present, had insisted that she and the kids go with him. She had the family’s belongings already tied in bundles, and Gus and George loaded them into the wagon. As the family got ready to leave, Gus kissed his mother goodbye, and Martha begged her son not to go, warning him that the Taylors might be laying a trap for him. Ignoring her misgivings, Gus loaded up his family, and the wagon started south toward Browning shortly before midnight.

The next morning about daylight, six-year-old Nellie Meeks came crying to the John Carter farmhouse, adjacent to the George Taylor farm, with blood and straw matted in her hair and her clothes and face bloody. She told Carter’s wife, Sallie, that she spent the night in a haystack on the adjoining farm, that her little sisters were still there, and that her parents were up the road, all of them having been killed and dumped by two men. Mrs. Carter sent her nephew, ten-year-old Jimmie, over to the Taylor farm to investigate, and the boy was met by George Taylor, who was harrowing the field near the haystack. When Jimmie told his neighbor that the little girl said her sisters were in the haystack, Taylor asked what she had said about her parents, even though the parents had not been mentioned. Then, instead of looking in the haystack as Jimmie suggested, Taylor immediately drove his team to his house, taking Jimmie along with him. Jimmie stayed with the team, while Taylor went inside, until Sallie Carter, who had been watching her nephew’s every move, motioned him to come home. As soon as Jimmie left, Taylor saddled up his horse and rode for Browning at a gallop.

Photo of Nellie Meeks, taken when she was about seven-years-old, not long after the rest of her family was killed. Meeks Collection, State Historical Society of Missouri.

On his way home, Jimmie looked under the haystack but didn’t see anything unusual. When he got home, Mrs. Carter sent him and Nellie back to the haystack together after the girl volunteered to show him where to look, and they discovered the four dead bodies. Mrs. Carter then alerted the neighborhood, and several people gathered at the haystack. Gus Meeks; his wife, Delora; their four-year-old daughter, Hattie; and their eighteen-month-old daughter, Mamie, had been killed and thrown in a hole that had been dug in the field where part of the haystack had been moved aside. Some dirt had been tossed on the bodies, and the stack had then been put back in place, covering the shallow grave with about a foot and a half of straw.

The isolated location near Jenkins Hill around where the Meeks family members were killed, still looking today much as one imagines it might have looked at the time of the murders. Photo by author.

Blood, a pistol, and other evidence were found at a place called Jenkins Hill about a mile and a half from the George Taylor farm on the road to Browning, indicating that the murders had been committed there. The adults and the baby had been shot, while the two older girls had been clubbed with heavy rocks. According to Nellie’s later testimony, both she and Hattie had awakened after being clubbed, but Hattie had been hit again when she started crying. Realizing that the same fate awaited her if the men knew she was alive, Nellie said she “kept still and never moved” until the men were gone, and then she made her escape.

It had rained the day before, making the ground soft, and investigators found the tracks of a wagon leading from the scene of the crime through a meadow and a cornfield to the haystack where the bodies were dumped. The tracks then led back to the road and into George Taylor’s lot, where a hired hand had found and taken charge of the Taylor wagon the morning after the crime. The hired hand said he had seen George Taylor earlier that morning washing mud and clay from the wagon and team, that he had noticed blood still on the wagon when he delivered it to George’s father on an adjoining farm, and that the father had tried to scrub it off. It was also noted that, because of the wet ground and the fact that his corn crop had only recently been planted, there was no logical reason that George Taylor should have been harrowing except the obvious one—to try to cover up the wagon’s tracks.

Reaching Browning about 8:00 a.m., George Taylor informed his brother of the unexpected and alarming resurrection of Nellie Meeks, and the two men mounted up and started out of town to the east, “riding hard,” according to a witness. At their father’s farm about a half mile east of George’s place, they left their horses and took to the timber on foot.

News of the murders reached Browning shortly after the Taylors had fled, and search parties began organizing to track the brothers, as word of the crimes was telegraphed to surrounding towns. Meanwhile, the bodies of the victims were hauled in a wagon to Browning, where they were placed in crude coffins with mud still on their faces.

Meeks family, dead. Meeks Collection, State Historical Society of Missouri.

Nellie Meeks was brought to Browning in a separate conveyance, and she told her story to area-newspaper reporters, who arrived on the scene just hours after the crimes had been discovered. Later the same afternoon, May 11, she repeated it to the coroner, who arrived from Bucklin. Nellie said that two men took her and her family away from Milan and that, as they were going up the hill, the one without whiskers (George Taylor) got out of the wagon and, while walking alongside it, shot her father. Next they shot her mother and hit her sister Hattie with a stone. Then they struck her with a stone, and she “went to sleep” and didn’t know any more until she and Hattie awoke as the men were putting them in the stack of straw. After the men killed Hattie when she began to cry, the one with whiskers (Bill Taylor) kicked Nellie in the back, but she let out not a whimper. “They are all dead now,” the man announced, “the damn villain sons of bitches.”

The men then covered her up, and she thought she was going to suffocate because she could barely breathe. She heard one of the men complain that something would not burn, and she thought they were trying to set the straw on fire, although it was apparently a blanket they were trying to burn nearby in order to dispose of it.

After hearing Nellie’s testimony and examining other evidence, the coroner’s jury concluded that the members of the Meeks family had come to their deaths at the hands of William and George Taylor.

Early on Saturday, May 12, the Taylor brothers were spotted near the home of Bill’s brother-in-law, not far from their father’s farm, but they disappeared into the timber again and escaped.

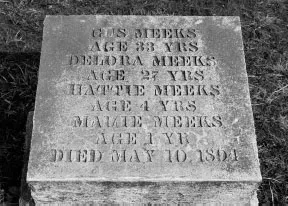

Later the same day, the bodies of the four victims were shipped to Milan, where a local undertaker cleaned up the corpses and lined the coffins. On Sunday, May 13, the bodies were viewed by hundreds of curious spectators and then taken to the Bute Cemetery (often spelled Butte) about twelve miles southeast of Milan. A funeral service reportedly attended by thousands was held at the site, and afterward all four bodies were buried in a common grave.

Meanwhile, the fugitives made their way south through southern Missouri and finally holed up in Buffalo City, Arkansas, where Bill, whose middle name was Price, assumed the identity of William Price, and George, whose middle name was Edward, became George Edwards. On June 25, however, they were captured by Arkansas state legislator Jerry South, who recognized them from pictures he had seen in a St. Louis newspaper. They at first offered a token resistance and denied they were wanted. Confronted with the story in the St. Louis paper, however, they admitted to their identities and became so tractable and ready to face the charges against them that South became convinced of their innocence. Nonetheless, he brought his prisoners by train back to Missouri from Little Rock in order to collect the $2,100 reward money that had been offered, $1,500 for their capture and another $600 for their conviction.

Meeks family gravestone at Bute Cemetery (aka Bunch Cemetery) in southeast Sullivan County. Photo by author.

South and his captives were met in St. Louis by Linn County sheriff Ed Barton, and the party started for Linn County on June 28. A large group of men bent on vigilante justice were gathering at the Brookfield depot in anticipation of the prisoners’ arrival, but Sheriff Barton, aware of the rumors of mob violence, bypassed Linn County and took the prisoners on to St. Joseph, where they were lodged in jail to await their trial at Linneus. The return of the fugitives from Arkansas had gone so smoothly that a few cynics accused South of being in cahoots with the Taylors in a scheme to share the reward money with them, but he vehemently denied the charges of collusion.

In December 1894, the Taylors were brought from St. Joseph to Linneus, where they were formally arraigned. Their lawyers immediately asked for a change of venue, and the case was moved to neighboring Carroll County, southwest of Linn. The prisoners were taken to the Carroll County jail at Carrollton to await trial.

In mid-March 1895, the Taylors went on trial at Carrollton on a charge of murder in the first degree in the death of Gus Meeks. The other charges were put on hold, since the prosecution felt proving premeditation would be easier in the case of the father. The brothers came into court well groomed and reportedly exuding an air of confidence. Train-car loads of spectators poured in from Linn and Sullivan Counties to attend the proceedings.

The state’s evidence was similar to but more extensive than that presented at the coroner’s inquest. The prosecution did not ask little Nellie Meeks to testify but instead relied heavily on the testimony of Sallie Carter and her nephew Jimmie. At least two men stated that they had heard Bill Taylor threaten to kill Gus Meeks in order to “get the S.O.B. out of the way” so he couldn’t testify against Taylor. Martha Meeks, who swore that the Taylor brothers had taken her family away in a wagon on the night of the murder, was also a key witness. Jerry South, who had become convinced of the Taylors’ guilt since capturing them in Arkansas, testified for the state that Bill Taylor admitted during the trip back to Missouri that he and George had picked up the Meeks family in Milan on the night of the murder but that they had given Gus the money, wagon, and team as promised and left him and his family at a junction about a mile east of Browning, where the road from Milan intersected the road that ran from Browning to the George Taylor farm. In addition, several witnesses placed the Taylors on the road between Browning and Milan at the time in question.

The defense’s strategy was to try to establish an alibi for the Taylor brothers. Testifying in their own defense, both Bill and George now claimed that they had been home all night on the night the murders were committed. George said that, after Jimmie Carter told him what Nellie Meeks had said, he looked under the haystack, recognized Gus Meeks’s body, and went to town to get authorities but that he and Bill decided to flee because, knowing they would be suspected, they feared mob violence. Many of the defense’s other witnesses were family members. Both Bill’s wife, Maude, and George’s wife, Della, backed up their husbands’ claims to have been home on the night in question. George’s mother-in-law, Argonia Gibson, confirmed her daughter’s story, saying that she had spent the night at the Taylor house and that George was there. James Taylor and his wife, Caroline, both claimed that the substance on their wagon that the prosecution identified as blood was actually red paint. A few other witnesses were introduced who claimed to have seen the Taylors at or near Brow...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- One: The Turk-Jones Feud: The Slicker War of Benton and Polk Counties

- Two: Burned at the Stake: The Lynching of Three Missouri Slaves in July 1853

- Three: Stranger Than Fiction: The Romantic Escapades of Desperado Billy Martin

- Four: The Greatest Sensation in Missouri History: The Assassination of Jesse James

- Five: The Most Noted Murder Case in McDonald County History: The Mann-Chenoweth Affair

- Six: The Murder of the Meeks Family: The Most Horrible and Brutal Crime in the Annals of Linn or Sullivan County

- Seven: Two St. Louis Legends: Stagger Lee Shot Billy and Frankie and Johnny Were Sweethearts

- Eight: You’ve Killed Papa and Now You’re Killing Mama: The Most Brutal Murder Ever in Cape Girardeau County

- Nine: Down for the Count: The Murder of Middleweight Champ Stanley Ketchel

- Ten: A Dirty Mixup All Together: The Notorious Welton Murder Case

- Eleven: The Kansas City Massacre: An Arena of Horror

- Bibliography

- About the Author