- 158 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The story of a devastating episode of the brief, bloody Black Hawk War—includes illustrations.

The brief war that Black Hawk waged against the United States in 1832 saw half of the people under his leadership killed in savage massacres and the entire Sauk tribe removed to Iowa. Yet this dismal outcome cannot obscure the superb military leadership that Black Hawk demonstrated during many phases of the war.

His crowning glory occurred at a place called Wisconsin Heights, where his force of about 120 warriors held off an estimated 700 American militia volunteers while the women, children and elderly under his protection escaped across the Wisconsin River. This book tells the dramatic story and includes maps and illustrations.

The brief war that Black Hawk waged against the United States in 1832 saw half of the people under his leadership killed in savage massacres and the entire Sauk tribe removed to Iowa. Yet this dismal outcome cannot obscure the superb military leadership that Black Hawk demonstrated during many phases of the war.

His crowning glory occurred at a place called Wisconsin Heights, where his force of about 120 warriors held off an estimated 700 American militia volunteers while the women, children and elderly under his protection escaped across the Wisconsin River. This book tells the dramatic story and includes maps and illustrations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Battle of Wisconsin Heights, 1832 by Patrick J Jung in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Origins of the Black Hawk War

The Black Hawk War, in a sense, started when Europeans settled the North American continent. In the early 1600s, the Sauk tribe lived in the Saginaw River Valley in the lower peninsula of Michigan, while the Foxes (who called themselves the Mesquakies) lived nearby in southern Michigan and northeastern Ohio. It was at this time that the French established settlements in eastern Canada. Both the Sauks and Foxes spoke the same language within the Algonquian language family and once had been a common people (along with the Kickapoos) several centuries earlier. The Five Nations League, composed of Iroquoian-speaking tribes in New York, attempted to dominate the Great Lakes fur trade with the Europeans in the 1640s and 1650s by annihilating other Indian communities in the region and in the process pushed these tribes and others westward. By the end of the 1600s, the Sauks and Foxes lived in northeastern Wisconsin.1

Later, some Foxes returned to their original homeland in southern Michigan and became embroiled in hostilities with tribes allied to the French. About one thousand Foxes died in an armed clash with these tribes near the French outpost of Detroit in 1712, thus precipitating a twenty-year series of conflicts with the French known as the Fox Wars. By 1732, the French had reduced the tribe to a mere two hundred souls, all of whom sought refuge the next year with the more populous Sauks at Green Bay. This began what would be a long period of political confederation between the two tribes. While they retained separate political structures, the Sauks and Foxes coordinated their external relations with European powers and other Indian communities. Indeed, the appellation “Sauk and Fox” became the term by which others referred to these two distinct yet allied tribes. The French launched a final genocidal war against the Foxes and their Sauk allies in 1733, but both tribes managed to escape farther west toward the Mississippi River. After a final, failed campaign in the winter of 1734–35, the French, unable to achieve their military goals, made peace. The two tribes remained in the Mississippi River Valley for the next century and had village sites that stretched from the Des Moines River in the south to the Wisconsin River in the north. The Sauk village of Saukenuk, one of the largest, stood at the confluence of the Rock and Mississippi Rivers. It was here that Black Hawk was born in 1767. By the early 1800s, the Sauks had a population of about fifty-three hundred, while the Foxes, who slowly recovered from the Fox Wars, had a population of about sixteen hundred.2

Sketch of Pontiac, Ottawa chief and leader of Pontiac’s Rebellion. From History of Jo Daviess County, Illinois, 1878.

The French lost control of North America after the French and Indian War from 1754 to 1763. Like many tribes in the Midwest, the Sauks were initially leery of the British. Some of them, along with Ojibwa allies, participated in the massacre of the British army’s garrison at the Straits of Mackinac in 1763. This was part of a larger, loosely coordinated set of uprisings known as Pontiac’s Rebellion led by an Ottawa chief from Detroit by the same name. The British soothed the hard feelings the war caused by reestablishing the system of trade that the French had developed. This system allowed the Indians to have political and cultural autonomy within the lands over which the French and later the British claimed suzerainty in exchange for allegiance and peaceful trade. In the period after Pontiac’s Rebellion, the British established control over Canada and the American Midwest; France gave its vast colony west of the Mississippi, known as Louisiana, to Spain as a reward for its support during the French and Indian War. Almost immediately after this conflict ended, the American Revolution began. When the war was over, the new United States assumed control of the former British lands that stretched from the Great Lakes in the north to the Florida panhandle in the south and the Mississippi River in the west. The British retained control of Canada, and Spain continued to exercise dominion over Louisiana. During these decades, the Sauks and Foxes found themselves in the very uncomfortable position of having to carefully balance their external relations with these three competing powers. For example, in 1780, during the American Revolution, the British forced the Sauks to attack St. Louis (then in Spanish Louisiana) because Spain had allied with the United States. The Sauks mounted only a halfhearted, unsuccessful attack. Their poor performance displeased the British, but it nevertheless angered the Spanish and the Americans, and a month later a combined Spanish-American force attacked Saukenuk.3

In the end, however, the United States would be the source of the greatest number of problems for the Sauks and Foxes. This was because the United States, unlike France, Britain or Spain, did not seek to establish a loose empire in the vast expanses of North America in which the Indians could continue to live as they always had as long as they traded their valuable furs for goods of European manufacture. The United States was willing to administer its new western territories in this manner for a short period, but this was seen merely as a transitional phase. Ultimately, the United States wanted to purchase the Indians’ land by what were known as land cession treaties. Often, the Indians negotiated these treaties in a position of weakness vis-à-vis the United States. Thus, they were often coerced into “voluntarily” selling their land. The federal government then forced the Indians to leave in order to make room for white settlers. This was the case with the Indians of the Ohio country. These tribes fought against the United States in the Northwest Indian War from 1785 and 1795. The Indians lost and were forced to cede the Ohio country to the United States by the 1795 Treaty of Greenville. Indians farther to the west, such as the Sauks and Foxes, watched these events with concern, for they rightly feared that the United States might make them the next victims of this insidious policy. Black Hawk was a young man at the time, and he expressed the sentiments of his people when he stated that “we had always heard bad accounts of the Americans from Indians who had lived near them!”4

The Sauks and Foxes became targets of this policy much sooner than they expected. The leader of France, the imperious Napoleon Bonaparte, decided to establish a new French empire in North America. In 1802, he secretly purchased Louisiana from Spain. This sent shivers down the spine of President Thomas Jefferson, who feared having an aggressive European power directly across the Mississippi River from the relatively weaker United States. Jefferson decided that the United States needed to purchase Indian lands on the east bank of the Mississippi in order to counter possible French aggression. Thus, in 1802 he instructed the War Department (which had responsibility for Indian affairs) to purchase southwestern Illinois from the Kaskaskia Indians; the land cession treaty effecting this transaction was signed in 1803. That same year, Jefferson concluded the purchase of Louisiana (better known as the Louisiana Purchase) from Napoleon, thus precluding the need to buy additional Indian lands. However, he wanted to ensure that no other tribes had claims to the lands ceded by the Kaskaskias. Thus, in June 1804, his secretary of war instructed William Henry Harrison, the governor of Indiana Territory (and later the president of the United States for a month), that “it may not be improper to procure from the Sacs [sic], such cessions on…the southern side of the Illinois [River], and a considerable tract on the other side.”5

Portrait of Indiana territorial governor William Henry Harrison. From Frank E. Stevens, The Black Hawk War, 1903.

It was with this broad mandate that Harrison set the events of the Black Hawk War in motion. Harrison arrived at St. Louis in October 1804 to govern the upper districts of the Louisiana Purchase. United States soldiers had taken possession of St. Louis, and the Sauks and Foxes were disturbed by this change of governance. Even worse, Americans began to establish settlements on what the Sauks insisted were their hunting grounds. One such settlement popped up about thirty miles northwest of St. Louis on the Cuivre River. In September 1804, a party of four Sauk warriors killed three white settlers there. This attack did not have the sanction of the tribal leadership, and to prevent retaliation by American soldiers, a delegation of four Sauks and one Fox went to St. Louis in October with one of the perpetrators to meet with Harrison, whom they hoped might extend clemency to the young warriors. In a way he did, but it was not what the delegates had in mind. Jefferson wanted to obtain Indian land for the growing United States, but he wanted purchases to be conducted in a just and humane manner. Harrison had no such scruples and aggressively sought to swindle the Indians out of their territory by any means. What happened during the course of Harrison’s meeting with the delegates is sketchy because no journal of the proceedings remains. The Sauk civil chiefs Pashipaho (The Stabbing Chief) and Quashquame (Jumping Fish) had been given the authority by the Sauk tribal council (and probably by the Fox council) to gain pardons for the perpetrators; they were not authorized to sell land. Also, the negotiation of land sales normally involved the entire leadership of a tribe, not a small, five-man delegation. Harrison agreed to pardon the perpetrator, who accompanied the delegates (and who now languished in prison), as well as his accomplices, in exchange for a land cession from the Sauks and Foxes. Harrison also dispensed whiskey and kept the delegation drunk during the deliberations. On November 3, 1804, the delegates signed the treaty, which ceded most of western Illinois, southwestern Wisconsin and a strip of eastern Missouri to the United States. For these fifteen million acres of land, the Sauks and Foxes received $2,234.50 worth of goods immediately and a perpetual annuity (or annual payment) of $1,000 in trade goods.6

It’s tempting to say that Harrison completely hoodwinked the delegates and that they had no idea the treaty sold their tribes’ land to the United States. However, the Sauk and Fox delegates probably were told during the negotiations that they were selling some land in exchange for freeing the young Sauk who accompanied them, as well as gaining pardons for the others involved in the Cuivre River killings. The question remains about how much and what land they thought they were selling. Quashquame asserted that the delegation had only sold a small bit of land north of St. Louis; this was an area used as hunting grounds where the two tribes had no permanent villages. This almost certainly would have met with the approval of both tribal councils since it would have ended the controversy over the Cuivre River affair. In later years, Sauk and Fox tribal members acknowledged that the delegates had sold land to the United States. However, it is clear in the historical records that they did not know how much of their country had been sold, and over time, as they gradually came to understand that virtually all of the two tribes’ domain had passed into the hands of the United States, the Sauks and Foxes expressed shock and outrage. Quashquame asserted for the rest of his life that he had never knowingly sold any land north of the Rock River—these were the most valuable and populated of the Sauks’ and Foxes’ country. To make matters worse, the young warrior held as a prisoner did not even live to see his freedom. He was shot dead while reportedly attempting to escape his captors. The entire sordid episode did much to increase the mistrust that the Sauks and Foxes already harbored against the United States. Later in his life, Black Hawk complained that the 1804 treaty “has been the origin of all our difficulties.”7

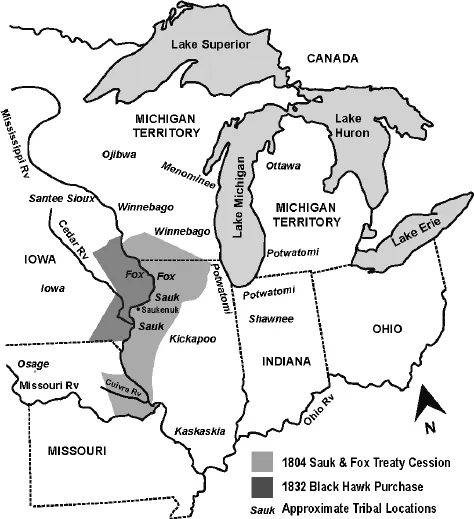

Sauk and Fox Land Cessions and Tribal Locations

Sauk and Fox land cessions and tribal locations. Map produced by the author.

Portrait of the Shawnee Prophet. From Thomas L. McKenney and James Hall, The History of the Indian Tribes of North America, 1836–1844.

The Sauks and Foxes did not have to leave immediately. The federal government first had to survey the land and open it for settlement, and that did not begin until the late 1820s. However, a series of tumultuous events occurred between the 1804 treaty and the 1832 Black Hawk War that exacerbated an already tense situation. The first began in the Shawnee lands to the east in present-day Indiana. There, in 1805, an Indian prophet arose by the name of Tenskwatawa, or “The Open Door.” He is better known as the Shawnee Prophet. After receiving a vision from a supreme deity he called the “Master of Life,” Tenskwatawa preached that Indians must lead virtuous lives and eschew the evil cultural trappings of white men. Except for firearms, a strict prohibition of the white man’s wares, particularly alcohol, was to be observed. He was not the first such Indian prophet, for Neolin (better known as the Delaware Prophet) had preached a similar message in the 1760s that sought to give Indians a sense of racial solidarity in their ongoing conflicts with whites. The Shawnee Prophet’s message, however, was not aimed at whites in general; it was aimed at Americans in particular. Moreover, it spread like wildfire among the Indians of the trans-Appalachian West, including the Sauks and Foxes. After 1808, the Shawnee Prophet resided at a village called Prophetstown at the confluence of the Tippecanoe and Wabash Rivers in Indiana, and Indians from as far away as Lake Superior came to hear his teachings. A significant number of Sauks and Foxes made the pilgrimage to Prophetstown. A party of 240 Sauks passed through his village in May 1810, and 1,100 Sauks, Foxes and Winnebagos arrived in June 1810. Many of them spread his message to other tribes. Whereas the Shawnee Prophet promulgated a religious message, it was his brother, Tecumseh, who used it to forge a political alliance among the Indians west of the Appalachians. Tecumseh had fought in the Northwest Indian War and was later determined to stop the sale of all Indian lands to the United States government.8

Sketch of the Shawnee Indian leader Tecumseh. From History of Jo Daviess County, Illinois, 1878.

The efficacy of the Shawnee Prophet and Tecumseh became evident in many tribes as strong anti-American factions arose that sought to translate the Shawnee brothers’ message into tangible action. This was particularly true of young warriors, for among the Indian tribes of the trans-Appalachian West, men gained social esteem primarily through great feats of bravery in battle. In the autumn of 1805, young Sauk and Fox warriors killed two white settlers in Missouri and another in present-day Iowa and later threatened to attack an American military detachment sent to arrest the perpetrators. In 1807, a Sauk warrior killed a white trader at Portage des Sioux in Illinois. The Sauks and Foxes were not alone, for young warriors from other tribes, particularly the Winnebagos, were also zealous adherents of the Shawnee Prophet and Tecumseh, and along with their confederates among the Kickapoos, Iowas and Potawatomis, they stole horses, killed livestock and attacked white settlers in Illinois and Missouri.9

American officials blamed the British in Canada for inciting the Indians against the United States, but the reality was far different. The United States and Britain had a tense relationship after the American Revolution. The British in Canada feared that the Americans might try to conquer their colonies in Canada. This was hardly a product of paranoia since the new United States had attempted, during the War of Independence, to seize the province of Quebec. While this attempt failed, the British nevertheless continued to cast a suspicious eye on their former colonial charges. Indeed, the Indians were not puppets of the British during the early 1800s; they were allies who had many of the same goals. Both the British in Canada and the Indian tribes of the trans-Appalachian West had a vested interest in preventing American expansion into their territories. Moreover, from 1807 onward, the British and the Americans began to drift toward war. The British in Canada sought allies for this coming conflict. Thus, the British maintained strong political relations with the tribes, particularly those in the United States. British agents invited Indians from lands under American sovereignty to Canada, where they lavished them with presents such as cloth and firearms. Malden, the British post across the St. Clair River from Detroit, was one of the principal meeting sites. Sauk parties regularly visited Malden.10

Both the British in Canada and their Indian allies went to war against the United States, and it was the Indians who delivered the first blow. In the autumn of 1811, William Henry Harrison, in his capacity as the governor of Indiana Territory, moved an American military force within a few miles of Prophetstown. Indian warriors present in the village (many of whom were Wisconsin Winnebagos) attacked on the morning of November 7, 1811. In what is known as the Battle of Tippecanoe, Harrison earned lifelong fame (and the nickname “Tippecanoe”) when he routed the Indian force. The battle was not decisive,...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Origins of the Black Hawk War

- 2. The 1831 Standoff and the Early Weeks of the War

- 3. Prelude to the Battle of Wisconsin Heights

- 4. The Battle of Wisconsin Heights

- 5. The Final Days of the Black Hawk War

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Works Cited

- About the Author