eBook - ePub

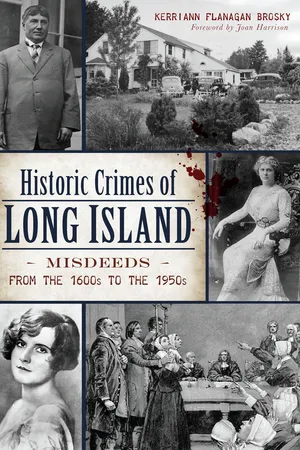

Historic Crimes of Long Island

Misdeeds from the 1600s to the 1950s

- 209 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This true crime collection reveals centuries of rogues, murderers, spurned lovers and accused witches who called Long Island home.

Author and historian Kerriann Flanagan Brosky uncovers some of the most ghastly and fascinating historical crimes committed on Long Island. Hidden just beneath the idyllic countryside and picturesque towns, there is a long and murky history of murder and mayhem.

A Victorian romance went awry in Huntington when wealthy farmer Charles Kelsey was tarred, feathered and murdered in 1872. Thirty-five years before the famous witch trials of Salem, East Hampton had its own Puritan hysteria among charges of witchcraft. The 1937 kidnapping of wealthy heiress Alice Parsons shook the quiet town of Stony Brook and remains a mystery to this day. These and other tales are revealed in chilling volume.

Author and historian Kerriann Flanagan Brosky uncovers some of the most ghastly and fascinating historical crimes committed on Long Island. Hidden just beneath the idyllic countryside and picturesque towns, there is a long and murky history of murder and mayhem.

A Victorian romance went awry in Huntington when wealthy farmer Charles Kelsey was tarred, feathered and murdered in 1872. Thirty-five years before the famous witch trials of Salem, East Hampton had its own Puritan hysteria among charges of witchcraft. The 1937 kidnapping of wealthy heiress Alice Parsons shook the quiet town of Stony Brook and remains a mystery to this day. These and other tales are revealed in chilling volume.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Historic Crimes of Long Island by Kerriann Flanagan Brosky in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781439662298Subtopic

North American HistoryCHAPTER 1

The Tarring, Feathering and Murder

of Charles G. Kelsey

of Charles G. Kelsey

HUNTINGTON

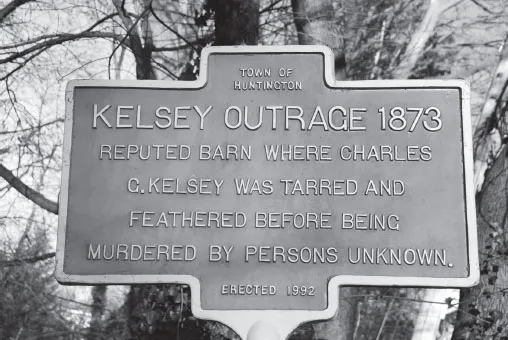

On November 4, 1872, a crime occurred in Huntington that shocked not only the town but the entire nation. The story began with beautiful Julia Smith, daughter of the influential Smiths of Huntington. Julia lived with her grandmother Charlotte Oakley in a large clapboard house that was located on Main Street near Spring Street, now Spring Road. An old red barn existed behind the house on what is now Platt Place. The barn was in terrible disrepair and was taken down in January 2001, leaving only a historical marker in its place. It was at this site that the first of two crimes took place.

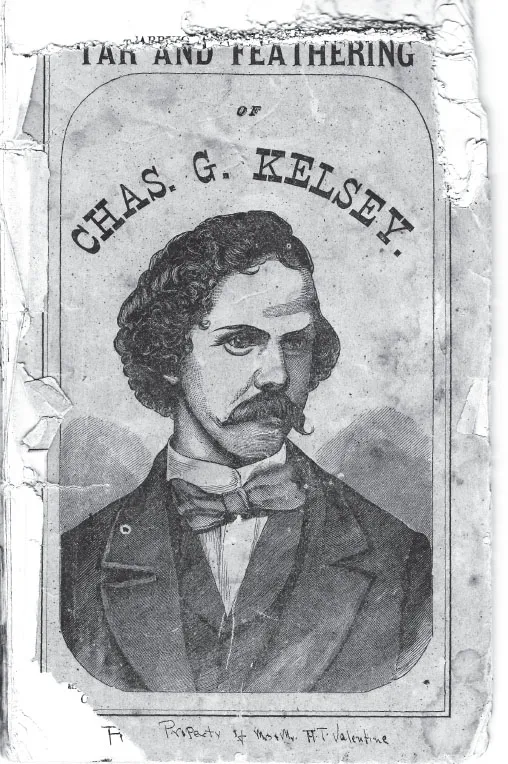

Charles Kelsey, a wealthy farmer, schoolteacher and poet, had fallen in love with the much younger Julia Smith. They were said to have had a brief romance despite Julia’s engagement to Royal Sammis, a member of one of Huntington’s most prominent families. Julia’s family, hearing of the romance, greatly disapproved of Kelsey and told the girl to end the relationship immediately. A brokenhearted Kelsey continued to write letters to Miss Julia that expressed both his anger and his love. Julia’s grandmother intercepted many of the letters, so Kelsey went as far as to mail them by way of New York City. This lasted only a short time. Mrs. Oakley began to tell her friends and neighbors (especially Dr. George Banks) about the letters, calling them “obscene” and even accusing Kelsey of enclosing pornography. This was never proven. Some of the letters were given to local reporters, who called them “crazy utterances of a lovelorn idiot.”

A historical marker designating the site of the tar and feathering of Charles G. Kelsey. Photo by Kerriann Flanagan Brosky.

One of Julia’s aunts, Abby Smith, was so suspicious of the letters that she decided to switch beds with her niece to see if Kelsey would come calling. Several nights later, while the aunt was sleeping, Kelsey is said to have entered the room through a window and attempted to make love to the aunt, who he believed was Julia. The aunt woke screaming and fled, locking the door behind her. When the aunt and grandmother went back to the room, it was empty, and they surmised Kelsey had left via the window. This tale was never proven, but in Victorian days, no one dared question a lady’s word. The story was taken as truth, and so it lived on.

It was this tale that provoked the violence that would soon take place. It was the night of November 4, 1872, the eve of Grant’s victory over Horace Greeley in the presidential election. The Democrats were holding a big rally, and many of the local hotels were filled with visitors. Charles Kelsey attended the rally, and when it was over, it appeared that Kelsey was on his way to his sister Charlotte’s home, half a mile up Spring Street where Charles lived. At some point, he had arranged a secret meeting with Miss Julia. She was to give him a signal when the coast was clear so he could come and see her. Unfortunately for Kelsey’s sake, this was a setup, because his love had forsaken him.

A portrait of Charles G. Kelsey. Huntington Historical Society Archives.

Apparently Julia deliberately trapped Charles by waving the lantern in the cellar window, giving her former beau the signal to visit. (Later, in her testimony in front of a jury, Julia admitted that she lured Charles with the lantern.) Upon his arrival, Kelsey encountered a band of masked men who jumped out from the backyard and stripped off his clothes. The men had been hiding beneath the branches of a willow tree, waiting for his arrival. Several of the men dragged out huge buckets of tar, while others brought large bags of feathers. In the barn, they cut off Kelsey’s beard and hair, poured the buckets of hot tar over his nude body and then covered him with feathers. Then the men dragged him to the front porch of the Oakley house, where Julia and her grandmother were waiting with some friends. A lantern was shone on poor Kelsey to prove, in the darkness, that it was in fact him. Enraged and humiliated, Kelsey lunged free, throwing his shoe at the lantern to extinguish it. However, one of the masked men grabbed the lantern and smashed Kelsey over the head. Finally, the men gave Kelsey his clothes back, and he ran off to his sister’s house.

From this point on, exactly what happened remains a mystery. Charles G. Kelsey simply disappeared. According to his sister Charlotte, she found a tar-covered watch without a chain in the kitchen, and there were signs of a struggle on the front lawn.

The next day, Charlotte and two other brothers, Henry and William, began a search but found nothing. Later that afternoon, a fisherman discovered a blood-soaked shirt on the shore of Lloyd Neck overlooking Cold Spring Harbor. The evidence was brought to the Kelsey brothers, who identified it as Charles’s shirt. Setting forth their belief in his death, Henry and William brought the shirt and an affidavit to Justice of the Peace William Montfort. They claimed their brother was “the victim of foul and unlawful treatment,” and an inquiry was opened in the village. Justice Montfort, based on the Kelsey brothers’ statement, charged Dr. Banks, Claudius B. Prime and Royal Sammis with riotous conduct and assault. The grave charges were sustained by the grand jury in a subsequent indictment.

Within days, all over the East Coast, Huntington was branded with the name “TAR TOWN.” The town became the target of every newspaper writer around, and the story spread nationwide. The incident created political problems in Huntington as well, for the once-quiet town was divided into the “Tar” and the “Anti-Tar” parties. The “Tars” were relatively small in number but were wealthy and influential, while the “Anti-Tars” opposed the outrage and held to the principles of law and order. This group was composed of many of Kelsey’s friends.

The barn where the Kelsey outrage occurred. It has since been taken down. Photo by Kerriann Flanagan Brosky.

It is said that even in his horrible condition, Kelsey recognized some of the masked men. Fearing exposure, the men may have followed Kelsey home and, under the motto “Dead men tell no tales,” killed him. In the hopes of concealing their identity, the body was perhaps brought to the deepest spot in the harbor with weights attached, in the hope it would remain out of sight forever.

It was hard for many members of the community to believe that such respectable men could be involved. Some were sympathetic toward the men accused of the outrage and claimed Kelsey deserved the punishment he got. They even believed that he was hiding out elsewhere in the United States and that he would one day return to seek revenge on his enemies.

The town was anxious to clear up the mystery, so Town Supervisor J.H. Woodhull offered a $750 reward for the production of the body of Charles G. Kelsey, dead or alive. The reward was then increased by $500 by Kelsey’s relatives.

Months went by with no sign of the body. In the meantime, Miss Julia Smith, seemingly unaffected by the event, married Royal Sammis in June 1873. Three months later, a grisly discovery would be made.

On August 29, 1873, fishermen John A. Franklin and William B. Ludlam were in two small boats in Oyster Bay when they noticed something strange floating in the water. Upon closer inspection, it appeared to be the lower portion of a human body. They fastened a line to it and towed it ashore, at which point they notified the coroner. When the body was found, it was covered in sea spiders.

More testimonies were heard, and other witnesses were called to the stand, some of whom included Charles’s youngest brother and the medical examiner. William S. Kelsey’s testimony was important as to the identification of the legs. He recognized the remains as being those of his brother. The legs had bits of tar and feathers on them, and he recognized the watch chain and the comb that had been on the body. The chain had been in the Kelsey family for twenty years, and the comb was one carried by his deceased brother. The pants could not be recognized by William but were later proven to be Charles’s when his tailor testified and proved the work he had done on the pants.

The medical examiner, Dr. M. Cory, gave a grisly account of just how brutal the crime was. In his statement, he said, “On closer examination I found that parts of the anatomy between the pelvis and knees were missing. I am of the opinion that it was the work of violence.”

Another doctor testified that the body was so terribly mutilated that it was a deed “expected from savages, not of peaceful Huntingtonians.” He believed the body had been weighted down with ropes that were tied around the waist, and the ropes were what cut through the torso.

The “Tar” crowd, despite the testimonies they heard, still argued that the legs were not Kelsey’s and that if they were, he had to have committed suicide. This did not stop Kelsey’s family from having a funeral service for him. They accepted the remains for burial, believing it was Charles, and preparations were made. To make matters even worse, an unidentified person posted a horrible notice mocking the services to come—the funeral services of “Legs.”

The funeral at the Second Presbyterian Church was jam-packed. Never before had Huntington seen such a huge crowd gather for a funeral. The pastor would not permit the legs in the coffin to be brought into the church. They were left outside on the lawn while services were going on. During a sermon, Charlotte Kelsey collapsed and was carried out of the church and into the crowd.

The remains were buried, but Huntington found itself the subject of bitter attacks in the nation’s press. Finally, under the pressure of every major newspaper in the state, Governor John Dix in Albany sent his own aide-decamp to Huntington to “clean up the mess.” He offered a $3,000 reward, an unbelievable sum for the day, for the arrest and conviction of Kelsey’s killers. The murder was considered one of the worst crimes of the century.

A coroner’s jury continued to hear evidence at the courtroom in Oyster Bay in September through October. (Nassau was then part of Queens County, which had jurisdiction over Cold Spring Harbor.) Coroner Valentine Baylis of Oyster Bay had ordered an inquest to determine whose legs were found and how they got there.

Frederick Titus, a Negro servant in Royal Sammis’s family, was a key witness. Under cross-examination, he admitted that Sammis told him he was going to tar and feather Charles Kelsey. However, his memory seemed to fail shortly afterward, and the same was true with the dozens of other witnesses who later took the stand. For years it was rumored that Titus never lacked a home or money to live on.

The jury made a decision on October 25, 1873, although it didn’t accuse anyone specifically of homicide. It ruled the “legs” were definitely Kelsey’s and that he “came to his death at the hands of persons unknown.” It found that “Royal Sammis, George M. Banks, Arthur Hurd, William J. Wood, John McKay and Henry R. Prince aided, abetted, countenanced by their presence committal of the gross outrage and inhuman violence.” They also ruled that Arthur Prime, Claudius Prime, S.H. Burgess, Rudolph Sammis and James McKay were accessories before the fact.

The local newspaper, the Long-Islander, argued from the beginning that the legs were not Kelsey’s and that it was a conspiracy of local politicians and Kelsey’s family to discredit some of the best families in town. It also insisted the trouble was being caused by New York City reporters who were “concocting their stories over the hotel bar.”

The testimony was finally sent to the grand jury, forty miles away in remote Riverhead. On November 7, 1873, the grand jury indicted Royal Sammis and Dr. Banks for riot and assault, the original charges made against them when Kelsey disappeared. A few hours later, the jury filed an indictment for second-degree murder against Royal Sammis and his brother Rudolph. The evidence provided by the district attorney for murder never showed up in open court. This, too, was a mystery.

Meanwhile, the fishermen finally received the $750 reward, but it cost Supervisor J.H. Woodhull his job. He lost the next election to Stephen C. Rogers because an injunction was filed against him claiming the reward was illegal, despite the orders that had been given to him by the people of the town. He had prepared a special bill for the state legislature to make the payment. Woodhull not only lost the election but was also forced to pay the $750 from his own funds.

The Sammises and Dr. Banks tried to get their cases transferred to Supreme Court in Brooklyn (Kings County) on the grounds that they could not get a fair trial in Suffolk. By 1874, rumors arose that Charles Kelsey was alive and living in California. It turned out to be Charles’s brother George, who had left Huntington twenty-five years before. Three years later, again in Riverhead, a jury hearing the evidence against Sammis and Banks returned a verdict of not guilty. In October 1876, Royal and Rudolph appeared in the same court demanding to be brought to trial or discharged. The district attorney released both men in their own custody with the stipulation that they appear when ordered to. For reasons unknown, the order never came.

Royal and Julia Sammis, Dr. Banks and several other central figures in the case moved to New York City to live their lives in seclusion. Despite search after search, the upper body of Charles G. Kelsey was never found.

CHAPTER 2

The Corn Doctor Murder

QUOGUE

The case of the corn doctor murder is an unusual tale of an eccentric podiatrist, Dr. Henry Frank Tuthill, known as “the corn doctor”; a bootlegging former police officer named Victor Downs; and a former cabaret entertainer named Mitzi Nowak Saunderson Downs.

The bizarre event that led to murder began in the quiet town of Quogue on the East End on the night of August 6, 1932. It was almost three years since the stock market had crashed, and the Great Depression was looming over the nation. The people of Long Island were nervous about putting their money in the hands of the banks. It was not uncommon for many people to hide and carry large amounts of money on their person, stuffed in boots and clothing. Dr. Henry Frank Tuthill was one of those people.

What made Dr. Tuthill a little different is that he was known to tell the world about the money he carried around with him. He was a bit odd, in many ways. He was a practicing chiropodist, which basically is a podiatrist. A chiropodist was a more common word used back then. Dr. Tuthill did not like to be called by his formal name, so he told everyone to refer to him simply as the “corn doctor.”

The sixty-eight-year-old doctor was tight with his money. He did not have an office of his own, so he would travel around Quogue and Hampton Bays in an old flivver making house calls and treating people’s corns. At the day’s end, he’d head home to a room he rented from Mr. and Mrs. Fillmore Dayton in Quogue. Boardinghouses were popping up everywhere, and people would rent rooms rather than rent or buy a place of their own.

A Quogue sign. Photo by Linda Paris.

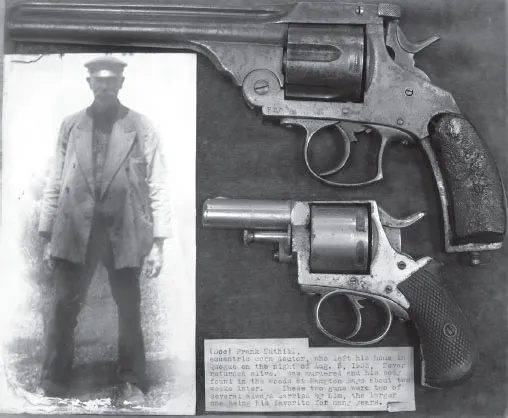

An image of Dr. Henry Frank Tuthill, “the corn doctor,” with two of his guns. The Collection of the Suffolk County Historical Society.

Most people on the east end knew who Henry Tuthill was. No matter what the temperature was, he was always wearing not one but two long, black overcoats. It was in ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. The Tarring, Feathering and Murder of Charles G. Kelsey: Huntington

- 2. The Corn Doctor Murder: Quogue

- 3. The Maybee Murders: Brookville

- 4. Kidnapping or Murder? The Alice Parsons Case: Stony Brook

- 5. East Hampton Witch Trial of 1658: East Hampton

- 6. The Woodward Murder: Oyster Bay

- 7. The Hawkins Murder: Islip

- 8. Starr Faithfull: Drowning, Murder or Suicide?: Long Beach

- 9. The 1842 Alexander Smith Murder: Greenlawn

- 10. The Mad Killer of Suffolk County: Islip, Smithtown, Westhampton Beach

- 11. The Murder of Captain James Craft: Glen Cove

- 12. Jealousy Leads to Murder: Quogue

- 13. The Samuel Jones Murder: Massapequa

- 14. The Wickham Murders of 1854: Cutchogue

- 15. Dentist Shot by Vengeful Mother-in-Law: Northport

- 16. Count Rumford and the Old Burial Ground: Huntington

- 17. The Tale of Captain Kidd and Buried Treasure: Gardiner’s Island, East Hampton, Oyster Bay

- 18. Gardener Kills Broker in Front of Bride: Duck Island, Asharoken

- 19. Mysterious Shooting in Freeport Doctor’s Office: Freeport

- 20. Captain Carpenter Murdered at Sea: Glen Cove

- Bibliography

- About the Author