- 131 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Battle of South Mountain

About this book

"A thorough account of the fighting . . . Not only appealingly written but a worthwhile addition to Maryland Campaign literature." —

Historynet.com

In September 1862, Robert E. Lee led the Army of Northern Virginia north of the Potomac River for the time as part of his Northern invasion, seeking a quick end to the war. Lee divided his army in three, sending General James Longstreet north to Hagerstown and Stonewall Jackson south to Harper's Ferry. It was at three mountain passes, referred to as South Mountain, that Lee's army met the Federal forces commanded by General George B. McClellan on September 14. In a fierce day-long battle spread out across miles of rugged, mountainous terrain, McClellan defeated Lee but the Confederates did tie up the Federals long enough to allow Jackson's conquest of Harper's Ferry. Join historian John Hoptak as he narrates the critical Battle of South Mountain, long overshadowed by the Battle of Antietam.

"A remarkable work . . . The marches of both armies to South Mountain are presented with close attention to the men in the ranks. The combat is fully covered at each of the gaps in South Mountain." — Civil War Librarian

"A crisp, concise but comprehensive account of the battles at the four passes or 'gaps' across South Mountain on September 14, 1862 . . . A truly scholarly effort that will satisfy both serious Civil War students and the general reading public. For Maryland Campaign aficionados, it is a must have addition to your library and is now the definitive account of the battle." — South from the North Woods

In September 1862, Robert E. Lee led the Army of Northern Virginia north of the Potomac River for the time as part of his Northern invasion, seeking a quick end to the war. Lee divided his army in three, sending General James Longstreet north to Hagerstown and Stonewall Jackson south to Harper's Ferry. It was at three mountain passes, referred to as South Mountain, that Lee's army met the Federal forces commanded by General George B. McClellan on September 14. In a fierce day-long battle spread out across miles of rugged, mountainous terrain, McClellan defeated Lee but the Confederates did tie up the Federals long enough to allow Jackson's conquest of Harper's Ferry. Join historian John Hoptak as he narrates the critical Battle of South Mountain, long overshadowed by the Battle of Antietam.

"A remarkable work . . . The marches of both armies to South Mountain are presented with close attention to the men in the ranks. The combat is fully covered at each of the gaps in South Mountain." — Civil War Librarian

"A crisp, concise but comprehensive account of the battles at the four passes or 'gaps' across South Mountain on September 14, 1862 . . . A truly scholarly effort that will satisfy both serious Civil War students and the general reading public. For Maryland Campaign aficionados, it is a must have addition to your library and is now the definitive account of the battle." — South from the North Woods

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Battle of South Mountain by John David Koptak in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

“The Enemy…Means to

Make Trouble in Maryland”

In early September 1862, the United States was in great peril. The fortunes of war, which had shone so brightly on the Union war effort just several months earlier, had taken a decided turn in favor of the Confederacy. Out West, Southern forces under Generals Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith were sweeping north through Tennessee and into Kentucky, while in the East, where most of the eyes of the world were focused, the situation appeared even brighter for the nascent Confederate States of America. There, General Robert E. Lee, following up a summer’s worth of battlefield victories, decided to maintain his army’s hard-earned initiative and launch an invasion of Union soil. By early September 1862, America’s fratricidal conflict—which at its outset many believed would last only a few months after one strong show of force—had already been raging for nearly a year and a half, and at this point, it appeared as though the Confederacy might prevail.

Such had certainly not been the case just several months earlier. Indeed, in the early spring of 1862, in both East and West, the Union was triumphant. In February, Forts Henry and Donelson fell into Union hands, as did the city of Nashville. More good news followed when reports arrived of the Union victory at Shiloh. By the end of March, General Ambrose Burnside was completing a successful expedition along the North Carolina coastline, during which his men captured all the state’s important ports, excepting Wilmington. Port Royal, South Carolina, had also fallen to the Union, as had Norfolk, the Confederacy’s most important naval yard. And, as if all this was not bad enough, near the end of April, Admiral David Farragut captured New Orleans, the Confederacy’s largest city and principal port. Such success prompted the New York Herald and many others in the North to predict the war’s end by the Fourth of July.2

While news from throughout the South during that spring of 1862 was unsettling for the Confederacy, most of the attention centered on General George McClellan’s mammoth, 100,000-man-strong Army of the Potomac, creeping up the peninsula formed between the York and James Rivers and approaching dangerously close to the Confederate capital of Richmond. By the end of May, McClellan’s forces were within just a few miles of the city. Panic reigned in Richmond, and the Confederate government began taking steps to prepare for the city’s evacuation. These were certainly dark days for the Confederacy. Yet the pendulum of war would soon reverse its course.

On June 1, 1862, fifty-four-year-old Robert Edward Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia, taking the place of General Joseph Johnston, who had fallen wounded the previous day at the Battle of Seven Pines. In Lee, the Confederacy found an audacious commander, ever willing to assume bold risks, even in the face of seeming adversity. With McClellan’s army stalled on the doorstep of the capital, Lee launched a weeklong series of attacks, unprecedented in its bloodshed and known collectively as the Seven Days’ Battles. Although he lost a higher percentage of men than did McClellan, Lee’s offensive did the trick. Convinced that he faced overwhelming numbers, McClellan ordered his army to retreat, falling back to the safety of the Federal gunboats on the James River. The threat to Richmond was gone, and the Confederacy breathed easier. Confederate war clerk John B. Jones spoke for many when he succinctly noted that Robert E. Lee had “turned the tide” of the war.3

General Robert E. Lee, commander, Army of Northern Virginia. Library of Congress.

Yet Lee could not rest on his laurels. With the Army of the Potomac neutralized on the James, Lee turned his attention to another Union army just then organizing in northern Virginia. Patched together with Union forces that Stonewall Jackson had thumped in the Shenandoah, and augmented by Burnside’s newly arrived Ninth Corps, the Federal Army of Virginia was headed by Major General John Pope. Lee hoped to defeat Pope’s force before it could be reinforced by McClellan’s army, which was already being withdrawn from the James for that very purpose. Leaving a force behind to defend Richmond, Lee swept north and, during the waning days of August, achieved a smashing victory over Pope at Second Manassas, forcing the shattered Army of Virginia back to the safety of the Federal capital.

Within just ninety days, Lee had succeeded in taking the war from the gates of Richmond to the outskirts of Washington, along the way defeating two Union armies and clearing most of Virginia of Federal troops. By early September, hope had replaced the despondency that had prevailed throughout the Confederacy just three months earlier. And while the Confederacy was at its zenith, the Union had fallen on its darkest days. The Fourth of July came and went, and no longer were there any newspaper predictions of the war’s imminent end. Two armies—one shattered and one dispirited—limped back into Washington, while a growing dejection began to sound throughout the land, both on the homefront and in the ranks. Sergeant Henry Keiser of the 96th Pennsylvania summed up this sentiment nicely when he declared, “Things look blue.”4

Nevertheless, Robert E. Lee now found himself faced with a difficult dilemma: what to do next? He did not have many viable options. Despite fears in Washington, Lee entertained no thoughts of following up the retreating Union columns and attacking the capital. The fortifications were simply too strong and his army too weak for such an extensive undertaking. The countryside around Manassas, made desolate by war, was unable to support his army. He could not simply wait there and prepare for the next Union offensive, and falling back toward a more defensible line was simply out of the question. Both of these options would effectively give the Federals time to regroup from their defeats and surrender to them the hard-won initiative, which Lee would not allow. There was really only one choice that made sense: a drive north, across the Potomac; an invasion of Union soil.

Such a movement had much to offer. It was nearly harvest time, which meant Lee’s army would be able to gain some much-needed provisions from Maryland’s lush agricultural countryside. Taking the war across the Potomac would also relieve Virginia of the burdens of war and give the people of Lee’s native state a well-earned reprieve. There was even a possibility, however remote, that a sweep into Maryland would encourage the people of this slave-owning border state, with pockets of strong Southern leanings, to rise up and cast its allegiance to the Confederacy. These factors alone were a strong inducement to Lee, but he realized there was much more to be gained by a drive north, much more than just a gathering of food and fodder and the possibility of adding another star to the Confederacy’s banner. By sweeping north, Lee was hoping, above all else, to achieve yet another battlefield victory, this one on Union soil. Such a victory, thought Lee, might just go a long way toward ending the conflict in the Confederacy’s favor. Lee neatly summarized his chief motivation for launching the invasion in a postwar interview, “I went into Maryland,” declared the aging warrior, “to give battle.”5

With the North’s seemingly endless supply of manpower and its vastly superior industrial and manufacturing capabilities, Lee understood that the longer the war continued, the less chance at victory the Confederacy would have. To prevail in this conflict, thought Lee, the Confederacy would have to wear down the North’s willingness to fight, and the surest way to do this was to defeat its armies on the field of battle, to convince the Union that this was a war it would be unable to win. Such a mindset helps to explain Lee’s willingness throughout the war to assume many bold risks, and this was what motivated him in early September 1862 to lead his men across the Potomac and into Maryland. The timing of this campaign was also very important for Lee. The 1862 midterm elections were less than two months away, and Lee was hoping to capitalize on the growing antiwar movement in the North, further exacerbating the political and social divisions there, and bear an outcome on the elections, thus making it even more difficult for President Lincoln to continue to prosecute what was fast becoming an unpopular war.

Having thus decided on his plan of action, Lee began developing his strategy. He would cross the Potomac near Leesburg and drive straight north to Frederick, threatening both Washington and Baltimore. This action would also force the Union army to follow before it had time to catch its breath and heal its wounds from its summertime defeats and before the tens of thousands of new volunteers, arriving daily in Washington, could be properly trained and organized. From Frederick, Lee planned to turn west across both the Catoctin and South Mountain ranges and into the Cumberland Valley. This would allow him to establish safer lines of supply and communication south through the Shenandoah Valley and would also draw the Federals farther from their base at Washington. At this stage, Lee imagined, he could compel the Federals to attack him on good, defensible ground, and if all went well, he would achieve the victory he went north hoping to gain.

Late on September 3, General Lee summoned his military secretary Armistead Long to his headquarters near Dranesville, Virginia. Several days earlier, Lee had been thrown from his horse, spraining both wrists and fracturing a bone in one of his hands. With his hands wrapped in splints, Lee was unable to write what would become one of the more famous dispatches in the annals of the Army of Northern Virginia; instead, he dictated to Long. To President Jefferson Davis, Lee famously announced, “The present seems the most propitious time since the commencement of the war for the Confederate Army to enter Maryland.” The two main Federal armies that had been operating in Virginia under McClellan and Pope had been driven out of the state and were “much weakened and demoralized.” Although he could not attack them in the extensively fortified U.S. capital, by sweeping north across the Potomac, he would compel his opponents to follow. Such a move would free Richmond of any immediate threat, and seeking to further convince Davis of the advantages of such a campaign, Lee noted, “If it is ever desired to give material aid to Maryland and afford her an opportunity of throwing off the oppression to which she is now subject, this would seem the most favorable.”

Lee most likely did not have much faith in the people of Maryland rising up in great number to throw its support behind the Confederacy, but he did know this was a Confederate goal from the outset, and by including this in his justification of a northern campaign, he was making his case to Davis that much stronger. Lee admitted that a drive across the Potomac was attended with much risk and that his army was “not properly equipped for an invasion of an enemy’s territory. It lacks much of the material of war, is feeble in transportation, the animals being much reduced, and the men are poorly provided with clothes, and in thousands of instances are destitute of shoes. Still,” said Lee, “we cannot afford to be idle, and though weaker than our opponents in men and military equipments, must endeavor to harass if we cannot destroy them.”6

Confident in the president’s approval, Lee did not wait for a response from Davis; he instead ordered his columns to make their way toward the Potomac River crossings near Leesburg.

At the outset of the campaign, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was only loosely organized. Instead of neatly organized corps, Lee went into Maryland with an army composed of various wings, divisions and independent commands, an arrangement that would prove unwieldy and would come to haunt him in the days ahead. General James Longstreet’s command consisted of two divisions, under Generals David R. Jones and John Bell Hood, and one independent brigade, under Brigadier General Nathan Evans. Stonewall Jackson commanded Lee’s other large command, or wing. He had three divisions, including his old Stonewall Division, which began the campaign under General William Starke; Ewell’s Division, under Alexander Lawton; and A.P. Hill’s famed Light Division. Augmenting Longstreet’s and Jackson’s wings was a general reserve division under Major General Richard Anderson. On September 2, Longstreet and Jackson each had roughly twenty thousand men in their commands while Anderson had an additional fifty-seven hundred. Lee’s army was strengthened further by the arrival of three strong divisions from Richmond, which linked up with the army at the beginning of the Maryland Campaign. Lafayette McLaws brought seventy-six hundred men in his division; Daniel Harvey Hill added another eight thousand, while Brigadier General John Walker’s division contributed five thousand more. Each of these divisions would operate independently during the majority of the campaign, excepting brief periods when they were temporarily attached to either Longstreet or Jackson. Commanding the Confederate cavalry was Major General Jeb Stuart; he had roughly fifty-five hundred troopers, a number that included the recent arrival of Wade Hampton’s Brigade.

On paper, then, Lee had more than seventy thousand troops of all branches when he launched his campaign into Maryland, and although he would lose thousands of these men to straggling, he went north with a much larger army than has been traditionally described. Most accounts place Lee’s numbers at anywhere between forty to fifty thousand men, but this is simply too low a number. Even a commander as audacious as Lee would not have embarked on such an important operation with so few troops, and he certainly would not have separated his army five ways and spread it across more than twenty miles of unfriendly territory—as Lee would do within a week of coming north—if he had but forty or fifty thousand men. Bold, yes, but Lee was certainly not foolish.7

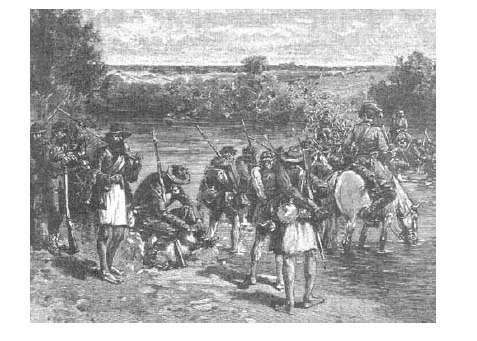

The Confederate invasion of Maryland commenced on September 4 when the first of Lee’s columns waded across the cool waters of the Potomac at White’s Ford, near Leesburg. It was a stirring scene, one that portended great things and one long remembered by those present. Heros Von Borcke, a Prussian-born officer serving on Jeb Stuart’s staff, left perhaps the most vivid portrait of Lee’s veterans splashing through the waters while being serenaded by regimental bands:

Confederate soldiers crossing the Potomac. Battles & Leaders of the Civil War.

It was, indeed, a magnificent sight as the long column of many thousand horsemen stretched across this beautiful Potomac. The evening sun slanted upon its clear placid waters, and burnished them with gold, while the arms of the soldiers glittered and blazed in its radiance. There were few moments, perhaps, from the beginning to the close of the war, of excitement more intense, of exhilaration more delightful, than when we ascended the opposite bank to the familiar but now strangely thrilling music of “Maryland, my Maryland.”8

By September 7, all of Lee’s columns had crossed the river and were either already encamped near or converging on Frederick, Maryland’s second-largest city, roughly forty-five miles northwest of Washington and fifty miles west of Baltimore.

The campaign began with much hope. Lee was confident and had great faith in his men and in the soundness of the campaign, believing a victory on Union soil would bring the Confederacy another step closer to victory.

Yet almost from the start, things began unraveling for the Confederate army commander.

The condition of Lee’s army was cause for concern. Despite their confidence, Lee’s men were worn-out, hungry and in such poor shape that one young Marylander famously described them as “the dirtiest men I ever saw, a most ragged, lean, and hungry set of wolves.”9 Of more immediate concern was the amount of straggling from the ranks. This was such a persistent and severe problem for Lee that he wrote of it frequently in his communications and reports on the Maryland Campaign. “One of the greatest evils…is the habit of straggling from the ranks,” Lee wrote to Davis on September 7. “It has become a habit difficult to correct. With some, the sick and feeble, it results from necessity,” said th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. “The Enemy…Means to Make Trouble in Maryland”: Lee Drives North

- 2. “Hell Itself Turned Loose”: The Struggle for Fox’s Gap

- 3. “My Men Were Fighting Like Tigers. Every Man Was a Hero”: The Fight for Frosttown and Turner’s Gaps

- 4. “The Victory Was Decisive and Complete”: The Battle of Crampton’s Gap

- 5. “God Bless You and All with You. Destroy the Rebel Army If Possible”: The Road to Antietam

- Order of Battle

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author