![]()

1

A DEATH IN THE LYRIC

The ringing telephone awakened James H. Shannon MD in the darkness before dawn. A few minutes later, he was walking swiftly up Main Street, bundled against the near-zero temperature. Snow was falling lightly on the Sunday morning of February 3, 1907. The only noise the doctor would have detected was that of his own footsteps until he had nearly passed the Lyric Theatre and heard a commotion in the alley. He turned and saw several men carrying what appeared to be a body into the doorway of the building at 78 North Main Street. One of the men hailed him, and he followed the group up the stairway and into a room, where they laid their motionless burden on a bed.

One look at the partially clothed young woman told Dr. Shannon she was quite clearly dead. Her face was still frozen in what he knew as “risus sardonicus,” literally “mocking laugh.” It was not so much the expression of the corpse that startled him, though, but rather the fact that he knew her.

Frances C. Martin was a pretty eighteen-year-old, with brown eyes, brown hair and a fair complexion, sturdily built at five feet, four inches tall and weighing 140 pounds. She had been to young Dr. Shannon’s office just three days earlier, when he found her to be in good health but also pregnant.

The Harvard-educated Shannon, at thirty years old, had only recently begun his practice in the borough of Washington, Pennsylvania, after having interned at hospitals in Boston, Massachusetts. He rented a room at the corner of West Prospect and Dewey Avenues and kept an office at 63 South Main Street.

Illustration by Robert Mish.

Frances had been upset by his diagnosis. Shannon would later testify at the coroner’s inquest that she told him she planned to kill the man who had done this to her and then kill herself. He testified that he advised her against doing so.

How Frances died, Shannon could not say just yet, but her last moments must have been in terrible agony. He turned his attention from the dead girl to the men who had carried her into the room: John T. Innis, twenty-seven, a tin worker who went by the nickname “Spikes”; John V. Cook, stage manager of the Lyric Theatre and into whose apartment the body was taken; and Daniel B. Forrest, thirty-seven, manager of the Lyric and a member of one of Washington’s most prominent families. There was something suspicious about their behavior. Why had they taken the girl’s body from wherever she died to the Cooks’ home? What were they trying to hide?

Shannon would need to fill out a death certificate, but the place where she died was obviously not where the group now stood. What Shannon told them was more accusation than statement of fact. “The girl did not die in this room,” he said.

None of the men who had carried her body from where she did die—the room above the box office in the Lyric Theatre—across the alley and into the stage manager’s home was a stranger to Frances. She had lived in John and Mary Cook’s home, where she was employed as a maid. The Cooks permitted her to go out on Saturday evenings with Innis, her boyfriend of the previous two years. And Innis was good friends with Forrest; they were the only two people who had keys to the bedroom above the box office that would, in the coming weeks, become the focus of civic outrage.

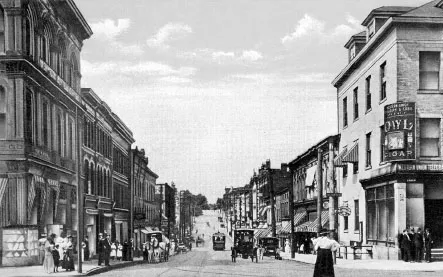

Main Street, Washington, circa 1910. Illustration by World West Galleries.

The mystery of Frances Martin’s death would be solved quickly, but its effects would reverberate through town for years to come. Moral decay was rotting the foundations of the borough, and the death in the Lyric would bring it all into the light.

FAST GROWTH AND FAST TIMES

Though it had been laid out a century earlier, Washington was, by 1880, still a sleepy little farming town of 4,292 souls, mainly the descendants of Scots-Irish settlers. But then a large pocket of gas was struck in 1884, an event that would change a village into an industrial city in a single generation. Washington would experience a boom in prosperity and population—and all the problems that come with such growth.

That gas well on the Hess Farm off Jefferson Avenue in Tylerdale was not the first drilled in the area, but it did prove to be the most productive. Within four months, many businesses in town and forty-six residences had gas service. Where gas is found, so is oil. By 1887, more than five hundred oil derricks were counted within the city limits, and production from the Washington field exceeded eighteen thousand barrels a day. The new millionaires built themselves grand houses.

It was the availability of natural gas, along with the huge reserves of coal in the region, that would have a lasting effect on the borough. Gas brought the Hazel-Atlas glass plant here in 1887, followed by Tyler Tube & Pipe in 1890. By 1895, Duncan & Miller, Highland, Phoenix, Novelty and Pittsburgh Window Glass were operating factories here. Findlay Clay Pot and Jessop Steel would follow in 1902.

With the industry came people. By 1890, Washington’s population had jumped 65 percent to 7,063. By 1910, it had increased to 18,778, making it the fastest-growing town in Pennsylvania. Part of that increase was due to the incorporation of South, West and North Washington, but the new jobs accounted for most of it.

The region’s ironworks were fueled by coal; mining coal was dirty, dangerous and labor-intensive. While American natives and immigrants alike were pouring into Washington to fill jobs in the new factories, coal companies were busy recruiting miners throughout Europe. Washington was suddenly a crowded town where at least half a dozen languages might be heard.

With the influx of people came crime and disease that offended the Presbyterian sensibilities of borough natives. Prejudice is apparent in local newspaper articles of the day, which were peppered with racial and ethnic slurs. The papers recognized the proper, upstanding townspeople and elevated them above the common rabble. Editorials began to focus on criminal activity and moral decay, but it is clear from news accounts of that day that drunkenness, debauchery, theft and corruption were not confined to immigrant households. Graft and bribery had seeped into politics and the police department, and those upstanding citizens with their newfound fortunes were keeping many a speakeasy and brothel in business.

Washington was a dry borough, officially, in that the sale of alcohol to the public was prohibited. Some private clubs were permitted to serve drinks, and doctors could prescribe alcohol to their patients for purchase at pharmacies. The demand for alcohol grew with the population. Washington had many clubs and twenty-five pharmacies dispensing beer, wine and liquor by prescription from some of the town’s forty-four physicians, many of them specializing in the practice.

Gambling was illegal as well, but townspeople didn’t have to look far for a poker game. Prostitution was rampant. The Observer reported in 1907 that it counted forty brothels, speakeasies and gambling houses in just one ward of the borough.

Washington’s residents spent their money on legitimate entertainment, too. The Opera House occupied the top floor of town hall, located where the county courthouse is now and moved in 1899 to Brownson Avenue. The Lyric Theatre, which could accommodate much larger stage productions, opened on North Main Street that same year. It was conceived and erected by W.D. Roberts and brothers Joshua and Robert Forrest, all prominent local businessmen. The Lyric opened in October with The Highwayman, a popular musical comedy of the day.

Lavish productions attracted the finest of Washington’s citizenry, but less respectable shows also took the stage. Several years into the twentieth century, talk began to circulate about the Lyric Theatre’s clientele. Young, attractive women with questionable reputations were rumored to be receiving free tickets and hooking up with seedy male patrons.

Some clergymen began referring to the borough as a cesspool. They preached that beer parties and drugs were luring children away from families. Police claimed they had no legal power to raid illegal establishments, but everyone else claimed the police were paid by the brothel and bar owners to protect them.

The body of Frances Martin was removed to this building at 78 North Main Street, Washington, where she was pronounced dead. Photo by the author.

Disgust grew and then gave way to shock when the events of the morning of February 3, 1907, became known. The Lyric—or more specifically, a bedroom above its box office—would capture the community’s attention, fascinate and sicken it and, finally, move it to action.

A GIRL IN TROUBLE

On the frigid morning that Frances Martin suffered an agonizing death, her boyfriend, John T. “Spikes” Innis, was arrested and lodged in the county jail. Though the cause was not known at the time, it was obvious to county detective William McCleary that Innis had something to do with her demise. Several witnesses told McCleary they had seen Innis with the young woman throughout the evening, and it was Innis who summoned help and was with her when she died.

Following a coroner’s inquest a few days later, Innis would be cleared of involvement in Frances’s death, but he would still face other charges that grew out of his testimony at the hearing: aiding in procuring an abortion.

Although he was advised by Coroner William Sipe that he was not compelled to answer questions, Innis was candid. He testified that he had known Frances for four years and had been intimate with her for the past eighteen months. More than a year earlier, in December 1905, when Frances was seventeen years old, she had informed Innis that she was pregnant. Innis said they talked it over and decided on an abortion. Shortly after Christmas that year, he went to Pittsburgh and procured the necessary instruments and drugs for the procedure, which was performed successfully in one of the rooms above the Lyric Theatre.

One year later, about three weeks before she died, Frances told Innis she was pregnant once again. This time, Innis testified, they talked about getting married.

Frances apparently had some doubts about her boyfriend’s commitment and sought the advice of a fortuneteller, who told her, “Spikes will never marry you.” After this, Frances drafted an agreement—one that she showed to her friends and which was entered as evidence at the inquest. It read, “I hear by [sic] state that on the tenth day of December, in the year 1906, that John T. Innis promised to marry Frances C. Martin after his mother’s death, and Frances Martin agreed to this and so did I.”

Innis testified that he had heard about the agreement but had never seen or signed it.

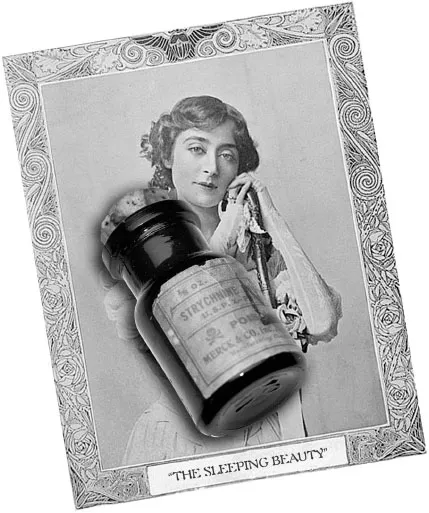

Frances had confided in a friend, Carrie Prowitt, that she was considering killing herself if Innis would not marry her. On January 26, Frances went to the McNulty Drugstore at 92 North Main Street and asked the druggist, Frank DeNormandie, for poison to kill a cat that she said “was running about with all the hair off it and about half dead.” DeNormandie advised her to drown the creature because strychnine was an awful death, and she left without buying it.

Irene Martin and her two other daughters were living in Indiana, Pennsylvania, at the time of her daughter Frances’s death. Mrs. Martin and daughter Elizabeth came to Washington when they were notified of the tragedy. The mother visited Innis in the jail on Monday, February 4, and afterward spoke with reporters. From what she told the press and later testified at the inquest, giving birth to an illegitimate child, or even death, would have been better for Frances than a life with Spikes. The following account of an interview with Mrs. Martin the day after her daughter’s death was published in the Observer:

The story told is a sorrowful one and showed the love of a mother for her child, regardless of what the past life of the girl had been.

…Innis had often abused Frances and had said he would choke her to death unless she did as he told her. Mrs. Martin says she has seen Innis choke Frances and has driven him out of the house while a resident of Washington because he insisted on abusing the girl.

What was the Lyric Theatre became the Washington Theatre in the 1920s. Courtesy of Observer Publishing Co.

At age fifteen, Frances had gone to work at the William H. Griffiths Tinworks, where she met Innis. At that time, her mother and two sisters were living in rented rooms on West Cherry Alley and later above a furniture store on East Wheeling Street, now occupied by Countryside Frame Shop. Her brother had been placed in a reform school. When her mother and sisters moved to Indiana, where they would find work at the new Pennhurst State School and Hospital, Frances became a domestic for John and Mary Cook, next door to the Lyric Theatre.

As “successful” as Frances’s abortion was, she lost her job in the Cook household over it. Mrs. Martin managed to convince her daughter to come to Indiana, but she testified at the coroner’s inquest that Innis had sent Frances money and persuaded her to return to Washington, where Mrs. Cook agreed to take her in again.

In agreeing to employ the recently disgraced Frances, Mrs. Cook had insisted that she not go out with Innis except on Saturday nights.

About 7:30 p.m. on Saturday, February 2, 1907, Frances told Mrs. Cook as she was preparing to leave for the theater that she would not return that night. She said she expected a final answer from Innis that evening, and if he refused, she would first kill him and then herself. But just before stepping out the door, Frances told Mrs. Cook, “I have thought of a better plan. I will have him arrested Monday.”

FRANCES’S LAST DATE

Mary Cook could hardly believe what Frances Martin had just told her: that instead of killing her boyfriend and then herself, she planned to have him arrested. The wife of the Lyric Theatre’s stage manager watched her hired girl walk out the North Main Street apartment and turn toward the theater next door. She would never see Frances alive again.

By 7:30 p.m., the air had turned colder, and a light snow began to fall. At the box office, Frances picked up the ticket that her boyfriend, “Spikes,” had left for her—a fifty-cent reserved seat—and walked down the long, narrow hallway past the poolroom to the theater.

The performance on the night of February 2, 1907, was Sleeping Beauty and the Beast, a Victorian pantomime. Advertisements for the show announced a company of sixty actors performing in the tradition of London’s Drury Lane productions. These were elaborate shows that featured stunning costumes and sets that changed quickly and often and mechanical devices that could rotate and elevate props and backdrops.

Daniel Forrest, manager of the Lyric Theatre. Library and Archives Division, Heinz History Center, Pittsburgh...