- 163 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

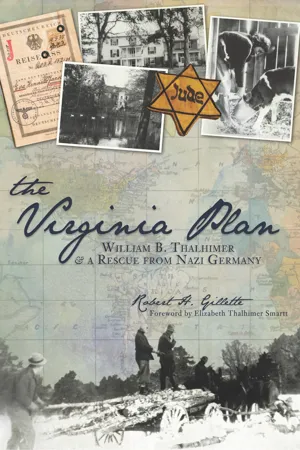

About this book

During Hitler's rise to power in the 1930's, Richmond department store founder, William Thalhimer and his family traveled to Germany to visit relatives and business contacts. Thalhimer was deeply disturbed and increasingly alarmed as the anti-Semitism that he and his family witnessed escalated into the violence Brown Shirts and Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass. Thalhimer became determined to aid Jews fleeing from Germany, and he eventually met a representative of Gross Breesen, a German-Jewish agricultural training institute. The mission of Gross Breesen, and eventually Thalhimer, was to train young Jews in agriculture in hopes that the expertise gained would ensure the students' successful emigration from Germany. Thalhimer purchased a farm, Hyde Farmlands, in Burkeville, Virginia to give the students a home in Virginia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Virginia Plan by Robert H Gillette in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1.

HOPE

In the late 1930s, Friedrich Borchardt, as an agent of New York’s Joint Distribution Committee, was charged with the enormous task of finding countries that would accept Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany. As he scoured Central and South America for potential opportunities, he searched for the faintest possibility of hope, much as an archaeologist sifts through the sands of antiquity yearning to uncover even the tiniest clue to a mystery of the past. Everyone who feverishly labored to find immigrant havens was haunted by the now famous words that had become a mantra of despair, the warnings uttered at a summer meeting in 1933. That meeting in Berlin gathered together the elite leaders of the German Jewish community, who knew one another well from business, professional and social activities. Hitler had been proclaimed dictator, and anti-Semitic activities were proliferating, with devastating effectiveness. The Jewish community was being crushed with each new Nazi edict. The atmosphere at the meeting was uneasy and tense.

The muted conversations of those assembled suddenly stopped when Rabbi Leo Baeck began to speak in almost a stage whisper. His round, metal-rimmed, penetrating eyes and bearded visage, along with his tall, imposing stature, made him appear ambassadorial. His words reverberated in the room and then exited to the world much as smoke ascends a chimney and disperses into the air: “Das Ende des deutschen Judentums ist gekommen!” (“The end of German Judaism has arrived!”) Rabbi Baeck saw with prophetic insight the horrible end of the Jewish People in his beloved homeland.1

A letter from his dear friend and colleague, Julius Seligsohn, a chief aide to Rabbi Baeck, reminded Borchardt that time for the Jews of Germany was running out. One sentence pleaded for his immediate attention: “I do not need to emphasize, dear Borchardt, to what an extent all of us who struggle greatly with the solutions of these difficult problems, count on your prudence and activity.”2 A German immigrant himself, Borchardt, treasurer of the Reichsvertretung (Central German Jewish Committee, or CGJC), was a board member of the Gross Breesen Agricultural Training Institute, which the Central Committee had created in 1936. Dr. Curt Bondy, a recognized social psychologist whose professorship had been stripped away by the Nazi legislative pogroms of the 1930s, was selected to head the school. Borchardt knew firsthand what was happening to the Jewish youth of Germany. He knew the truth: “If the future of adult Jews of Germany is hopeless, what shall we say of the future of Jewish children?”3 That is why Gross Breesen was created, to train Jewish adolescents in agriculture in hopes that countries would be willing to accept them for immigration. The goal: get out of Germany, quickly.

On that January day in 1938, Borchardt perused file after file in desperation, looking for a shred of possibility that could lead to a potential immigration placement. The doors of most countries had been slammed shut to Jewish immigration. He fingered the stiff file folders. He glanced at a letterhead printed with the words “Thalhimer Brothers, Department Store.”

William B. Thalhimer, who had been incredibly successful in resettling refugees in America, was the national chairperson of the Refugee Resettlement Committee of the National Coordinating Committee (NCC), the umbrella organization for Jewish immigration to the United States. Borchardt skimmed the letter that was addressed to the NCC Board. Several words must have appeared boldly in his mind: VIRGINIA, FARM, REFUGEES. His eyes must have been riveted to one particular sentence in which Thalhimer suggested that refugees “be settled upon farms in the rural communities of this country in order to relieve their increasing concentration in the cities and in addition… hasten the process of rehabilitation.”4 Thalhimer’s suggestion was general in substance, but Borchardt began to think in particulars. Attached to the letter was an acknowledgement of receipt, but there was no suggestion for further action or consideration. Would this Thalhimer be interested in settling the Gross Breesen students in Virginia? Prospects for finding new homes for the students were vanishing painfully each day. Perhaps, by some stroke of luck, this letter might lead to a willing partner.

Borchardt contacted Thalhimer to be assured of the seriousness of his intent. He was more than convinced, so he contacted Dr. Bondy with the hopeful news and arranged for the two men to meet in early February 1938 to discuss the possibilities. Borchardt became a broker of human cargo. This newfound prospect imbued him with renewed energy; could the three men become entwined in the rescue of the Jewish students from Gross Breesen?5

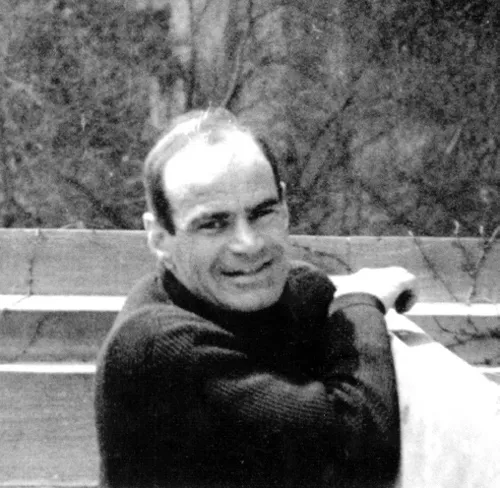

Bondy crossed the Atlantic, and Thalhimer traveled from Richmond. The two men met and an instant friendship was created. The personalities of the two were similar. They were both hard-driving, no-nonsense, sometimes brusque, forceful men who made decisions quickly but rationally. They both believed that hard work and integrity could overcome personal obstacles. Their word could be trusted with a handshake. But though they were blunt and at times heavy-handed, they could also be affable and charming. They were Jewish, of German roots, non-Zionist and totally consumed in their efforts to save and settle refugees.

Dr. Curt Bondy at Gross Breesen. From the Circular Letters.

It was from this initial meeting in New York that the Virginia Plan germinated. Bondy was hopeful that the establishment of a Gross Breesen colony in America could become a reality—at least it was given a chance. For Thalhimer, his vision of an agricultural center for Jewish refugees took on the glimmer of possibility. For the past eight years, since 1930, he had been plagued by the scenes of the Nazi Brownshirts he had encountered in Germany while on a combined business and family trip to Europe. The drumming and anti-Semitic chanting so branded him, so seared his heart, that he pledged to help those who would flee the growing madness. So, while he continued his refugee resettlement work under the auspices of the NCC and the Richmond Jewish Community Council, he set out to develop a new plan. Finding a farm to house the Gross Breesen students became his first item of business, another project in his passion to rescue the victims of Nazi Germany.

2.

FINDING A FARM

Late Winter, 1938

One can easily imagine the excitement that was ignited as William and his cousin and close friend, Morton Thalhimer, discussed the new resettlement plan. Morton was a very successful real estate broker who had a large network of realtors whom he could depend on for possible leads of farms for sale. His sharp eyes could spot the potential of a promising farm, and in the late 1930s Depression, it was a buyer’s market. The farm that the cousins searched for would have to fulfill certain requirements. It would need to be located not too far from Richmond in central Virginia. It had to be large enough to house potentially thirty young adults and staff, both male and female, and have expansion possibilities. Naturally, it would also have to be agriculturally viable. But of utmost importance, it had to be available soon.

In midwinter, the two were summoned to the small town of Burkeville, a rural community just a few hours south of Richmond. One can safely assume that the fact that the farm would house German Jewish refugees was not highlighted in exploratory conversations. Memories of World War I left little room for a positive view of Germans, and Jews were suspect in this farming community of white-power conservatives, some of whom were active Ku Klux Klan members. If a large political billboard had been erected near Burkeville, it would have been emblazoned, “This is Jim Crow Country.”

Even with these concerns, the cousins pushed on in their efforts to purchase a farm. They entered a time warp—the entirely different world of rural life in the 1930s. The differences between Richmond and Burkeville were stark. No matter. The two were shrewd businessmen, and Morton was an expert in conversing in real estate jargon. In Burkeville, they met the agent who was representing the seller of the farm. The three would have been dressed in business suits, vests, hats and overcoats, as the winter hung on.

As the three businessmen stood next to the roadside mailbox six miles south of town, any local farmer who passed by would have quickly spread the word that there was some real estate action going on at the farm. News spread rapidly in this rural town over the potbellied stove in the general store, over the seed counter and at the Sunday morning church gatherings. The name on the mailbox read R.J. Barron, and next to it was a painted sign for Hyde Park Farm.6 Before the three drove up the road that led to the farm, one of the Thalhimers probably asked the realtor, “What can you tell us about this farm?” In a slow though enthusiastic manner, he might have responded, “This place is full of history. It’s a great farm, but it was always a great farm.”

Hyde Park Farm had a pedigree that few others could boast. This was not just some parcel that was hacked out of the woods and transformed into fruitful fields. The birth of this homestead occurred in 1746 as a land grant patent bestowed by the king of England through his governor to Samuel and Hezekiah Yarbrough. In 1752, John Fowlkes purchased the nearly 1,500 acres over a few years and kept the farm in his family for five generations.7 The plantation was called Old Field, but when one of the Fowlkes sons, Paschal, married Martha Anne Hyde, the name was changed to Hyde Park.8 The farm survived the transformations that all large farms went through in central Virginia. By the mid-1800s, it had grown into a prosperous plantation. The 1860 slave census listed Hyde Park as owning forty-six slaves ranging in age from one to seventy years old: fifteen females and thirty-one males. The estate supported various crops, livestock, cotton and tobacco, the chief money crop.

William B. Thalhimer. Courtesy of the Thalhimer Family Archives.

Morton Thalhimer, cousin of William Thalhimer. Courtesy of the Virginia Holocaust Museum.

One story that has been attached to Hyde Park Farm involved the visit of the notorious John Brown, who stayed overnight. He traveled by the name of Dr. McLean, and his supposed secret mission was to stir the slaves into an insurrection. The visit gained credibility after John Brown’s raid, when his picture appeared in the newspaper and locals identified McLean as Brown. During the Civil War, Hyde Park Farm escaped being burned when Grant’s army marched to Burkeville on the very road that bordered it. Specific orders had been given by the officers that only food and water could be appropriated as the army advanced.

Nearby Burkeville was a railroad hub in the mid-1800s, with lines to Lynchburg to the west and the Carolinas to the south; it was of vital significance to the transport of troops and matériel for the Confederate forces, so it was a significant Union target. The Unionist troops scored a decisive victory at Burkeville, as the entire railroad facilities and tracks were completely destroyed. Smoke billowed high in the air and could easily be seen from the farm, as could the sounds of cannons reverberating throughout the area. Union generals Wilson and Kautz convincingly routed the retreating Confederate defenders of the town. The famous Battle of Sailors Creek was waged just north of the homestead.

Even though Hyde Park came out of the war unscathed, the owners contributed to the war effort nonetheless. In a personal letter written to Mrs. Paschal J. Fowlkes by Robert E. Lee, the general thanked her for the contribution of clothing to the war effort.9 Years later, the farm was purchased by a Northerner, Thomas B. Scott, who enlarged the main structure to include thirty rooms and a large ballroom for elaborate social events. It was a large house of eight thousand square feet, “known as one of the handsomest homes in the county.”10

The long driveway leading to the main compound was hard-packed clay mixed with some fine gravel. In late winter, it was soft but not muddy enough to make driving impossible. On that day, no farmer’s horses were needed to pull out a stranded auto, as often happened before roads were paved. The pastures adjacent to the drive were brown, though a hint of colored haze washed the trees in the dense forest. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword, by Elizabeth Thalhimer Smartt

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Hope

- 2. Finding a Farm: Late Winter, 1938

- 3. Bondy’s First Consular Meeting

- 4. Immigration Granite Walls

- 5. The “Virginia Plan” Begins

- 6. Visa Considerations: Round One

- 7. State/Labor Deliberations: Round Two

- 8. Germany in the Fall of 1938

- 9. Kristallnacht: November 10, 1938

- 10. Waiting for Immigration, 1939

- 11. “Root Holds,” 1939

- 12. Visa Deliberations After Kristallnacht

- 13. Journey to Hyde Farmlands, 1939–1940

- 14. Bleak News from Europe

- 15. Hyde Farmlands Expands, 1939–1940

- 16. Neighbors and Helpers

- 17. Nearby Towns

- 18. Encounters with a New Racism

- 19. A Community in Transition, 1940

- 20. 1941: A Fateful Year

- 21. After Hyde Farmlands

- 22. The War Years and After

- 23. A Final Accounting

- 24. Misconceptions

- 25. Shareholders for Life

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author