![]()

Chapter 1

THE BIRTH OF ABOLITIONISM

I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—AND I WILL BE HEARD.” These words were emblazoned across the first issue of The Liberator newspaper, published in Boston on January 1, 1831. With them, William Lloyd Garrison inaugurated a national abolitionist movement dedicated to the immediate end of slavery. Garrison, a white man, welcomed blacks and women to join him in opposing oppression. His paper and the radical movement it spawned would lead directly and inexorably to the Civil War thirty years later.

Garrison, who hailed from the North Shore town of Newburyport, announced his determination “to lift up the standard of emancipation in the eyes of the nation, within sight of Bunker Hill and in the birthplace of liberty.” The choice of Boston as his base was well made. While Garrison harshly criticized most Bostonians’ indifference to slavery, the city’s history of active abolitionism dated back to the Revolutionary era. Boston’s white Patriots, free blacks and slaves had acted on the promises of freedom contained in the Declaration of Independence to make Massachusetts, in 1783, the first state in the new nation to abolish slavery.

SLAVERY IN MASSACHUSETTS

Ironically, Massachusetts was also the first colony to legally endorse slavery, incorporating it in 1641 into the paradoxically named Body of Liberties, the colony’s first legal code. Yet voices early in the Revolutionary struggle would speak out against the practice. Patriot leader John Adams credited James Otis with initiating the movement for independence from Great Britain when Otis argued in 1761 that British writs of assistance, which allowed warrantless searches, violated “natural law,” which gave every man the right to life and liberty. “Then and there,” wrote Adams, “the child independence was born.” Several years later, Otis called attention to the inconsistency of arguing for freedom for the American colonies while denying it to a class of persons living in their midst. “The Colonists are by the law of nature free born, as indeed all men are, white or black,” he wrote.

When Otis published The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved in 1764, 2.2 percent of the inhabitants of Massachusetts were slaves. In coastal Boston, nearly 10 percent of the almost sixteen thousand residents were slaves. The largest slaveholding family, the Royalls of Medford, owned several dozen slaves. Though few Bostonians are aware of this aspect of their city’s history, Boston’s colonial-era newspapers advertised for the purchase and sale of slaves, and courts enforced contracts involving the sale of slaves.

Discussions over the future of slavery continued in Boston throughout the American Revolution. The legality of enslaving Africans was the subject of Harvard College’s commencement debate in 1773, the same year as Boston’s famous Tea Party. An unsuccessful attempt to outlaw the slave trade was made in 1774. That same year, local black poet and slave Phillis Wheatley wrote, “[I]n every human breast, God has implanted a principle, which we call love of freedom; it is impatient of oppression and pants for deliverance.” Abigail Adams, an acute observer of Boston mores and morals, told John Adams, her husband, who was serving in the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, “I wish most sincerely there was not a slave in the province. It always appeared a most iniquitous scheme to me [to] fight ourselves for what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right [to] freedom as we have.”

THE END OF SLAVERY IN MASSACHUSETTS

Demands for the end of slavery in Massachusetts increased following the colonies’ adoption of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. Led by Prince Hall, a free black man, Boston’s free and enslaved blacks organized a series of antislavery petitions to the Massachusetts legislature. The petition of January 1777, which relied on the soaring rhetoric of the Declaration of Independence, postulated that blacks enslaved in Massachusetts “have in common with all other men a natural and unalienable right” to freedom and alleged that every argument of the enslaved “pleads stronger than a thousand arguments” against Great Britain. The Massachusetts state constitution of 1780, drafted by John Adams and adopted while war with Great Britain raged, echoed the Declaration of Independence’s promises of equality and liberty. Article I of the constitution proclaimed, “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.”

Although the abolition of slavery was not a stated goal of Article I, some in Massachusetts saw a direct connection. In their votes to ratify the proposed constitution, delegates from several towns recommended explicitly outlawing slavery. The town of Hardwick proposed that Article I be revised to state, “[A]ll men, white and black, are born free and equal” so that it could not be “misconstrued hereafter in such a manner as to exclude blacks.” Braintree, where the Adams family lived, also sought an explicit end to slavery, explaining that “when we have long struggled, at the expense of much treasure and blood, to obtain liberty for ourselves and posterity, it ill becomes us to enslave others who have an equal right to liberty with ourselves.”1

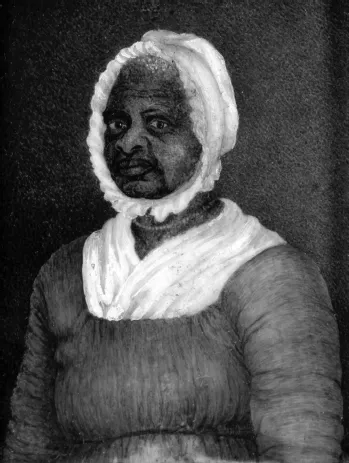

Soon after the Massachusetts Constitution was adopted, two court cases brought by slaves with the assistance of white lawyers ended slavery in the young state. In 1781, a household slave known as Mum Bett sued for her freedom after hearing a public reading of the Declaration of Independence. With assistance from lawyer Theodore Sedgwick, Mum Bett prevailed in her case. A jury in western Massachusetts concluded that the Massachusetts Constitution had effectively outlawed slavery and fined the man who had claimed to own her thirty shillings. Mum Bett was thereafter known as Elizabeth Freeman. She worked for Theodore Sedgwick’s family as a paid caretaker, and when she died, she was buried in a place of honor in the Sedgwick family plot. Sedgwick’s advocacy did not diminish his legal stature; he later served as a U.S. representative, a U.S. senator and a justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.

Mum Bett, also known as Elizabeth Freeman. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Also in 1781, Quock Walker, a black slave in Worcester County, ran away. His owner’s beating of Walker upon his recapture led to a series of lawsuits that challenged the authority of a “master” to beat his “property.” Levi Lincoln, Walker’s lawyer, argued, “Is it not a law of nature that all men are equal and free—Is not the law of nature the law of God—Is not the law of God, then, against slavery?” Garrison and other nineteenth-century abolitionists would later argue that a “higher” law of freedom took precedence over man-made laws codifying slavery.

William Cushing, the chief justice of the Supreme Judicial Court, instructed a Massachusetts jury hearing Walker’s case that slavery was incompatible with the rights set forth in the recently adopted constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts: “[Our constitution declares] that all men are born free and equal; and that every subject is entitled to liberty, and to have it guarded by the laws as well as his life and property. [S]lavery is in my judgment as effectively abolished as it can be by the granting of rights and privileges wholly incompatible and repugnant to its existence.”

The jury found that Quock Walker’s master lacked the authority to administer a beating. No Massachusetts slaveholder ever again attempted to assert a legal right to claim a person as property, and the 1790 census recorded no slaves in Massachusetts.

SLAVERY AND THE U.S. CONSTITUTION

In contrast to the soaring rhetoric of liberty and equality contained in the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution of 1787 explicitly permitted slavery, although the framers avoided using the term, aware that it would taint the nation’s charter. For purposes of appointing representatives to the U.S. House of Representatives, those “bound to service” were counted as three-fifths of a free person, thus ensuring that white voters in states with large numbers of slaves would exert a disproportionate influence on national policy. The “importation of such persons as any of the states now admitted shall think proper to admit” (slave trade) was protected until at least 1808. Article IV provided for the return of one “held to service or labor” who had escaped to another state.

These clauses stemmed from the compromises necessary to create the Union, although some founders vehemently protested these concessions to slavery. Future generations would have to resolve the chasm between the Declaration of Independence’s lofty promises and the Constitution’s legal rules. They would also have to determine whether the Constitution was permanently destined to be a pro-slavery document or if the commitments articulated in the Preamble—to “form a more perfect Union” and “secure the Blessings of Liberty”—contained the seeds of emancipation. This would, of course, require the nation to define whether liberty meant the right of slave owners to their property or the right of all people to be free.

THE GROWTH OF A NEW SOCIETY

The morality of slavery receded as an interest of Boston’s whites for several decades following the end of slavery in Massachusetts. Instead, concerns turned to local pocketbooks. Boston had taken a financial pounding during the Revolutionary War. When the British Trade Act of 1774 closed the port to all commerce, merchants shifted their business to other cities on the East Coast. Even after the peace treaty with Britain in 1783, the Port of Boston, which had been the economic engine of the city, regained traffic only slowly until the second decade of the nineteenth century.

After Francis Cabot Lowell opened the nation’s first textile factory in 1814 in suburban Waltham, Boston’s fortunes began to change. The city’s early industrialists, children and grandchildren of the Revolutionary Patriots, made fortunes from factories that transformed Southern slave-grown cotton into cloth. Slavery helped power the economic engine behind Boston’s resumed commercial success in manufacturing, banking, shipping, transportation and other industries. Close economic and social ties developed between those whom abolitionists would call the “lords of the loom” and the “lords of the lash.” These ties would continue to grow every year into the 1850s.

The issue of slavery first threatened to disturb this relatively tranquil period of growth in 1820, when the slave state of Missouri petitioned for admission to the Union. Its admission would have undone the careful balance between slave and free states. By this time, other Northern states had passed laws providing for the gradual end of slavery, and slavery had become a purely Southern affair. The Compromise of 1820 maintained sectional balance by admitting Missouri as a slave state and Maine (which had been a part of Massachusetts) as a free state. Further emphasizing that slavery was now a peculiarly Southern institution, the Missouri Compromise also banned slavery in all territory that had been acquired in the Louisiana Purchase north of the latitude of 36° 30´. Americans hoped that the Missouri Compromise had “solved” the sectional disputes over slavery, and the issue again largely receded from public debate.

AWAKENINGS

The religious revival movement known as the Second Great Awakening swept across the Northeast during the first decades of the nineteenth century. (The First Great Awakening was a mid-eighteenth-century Christian revival movement.) Before subsiding in the 1840s, the Second Awakening spread like wildfire through different Protestant denominations and led to a massive growth in the Methodist and Baptist denominations among both whites and blacks. Mass revival meetings sprang up, led by reformers who preached that salvation required working toward the moral perfection of individuals and society. The ethos of the awakening helped spawn a variety of social reform movements, including those for abolitionism, temperance, school reform and women’s rights.

Black churches were the center of Boston’s small and close-knit black community; the number of blacks living in Boston remained under two thousand even as the white population grew to sixty-one thousand by 1830. More than half of Boston’s blacks lived on the north slope of Beacon Hill. The First African Baptist Church, also known as the African Meeting House, opened on Beacon Hill in 1806, and a black Methodist church was established in 1818. The all-black African school (later renamed the Abiel Smith School) was initially located in the African Meeting House before moving to a building next door. Boston’s blacks typically eked out a meager living in unskilled and menial jobs, although some owned small businesses that catered primarily to their own community. Laws or customs of the white majority guaranteed discriminatory treatment or segregation of blacks in most aspects of daily life.

In 1826, members of Boston’s black community formed the Massachusetts General Colored Association to advocate for education and moral improvement and against racism and slavery. Among the association’s founders was David Walker, a black man who had been born free in North Carolina around 1796 and lived in Charleston, South Carolina, and Philadelphia before coming to Boston in 1825. Walker established a small used-clothing business and served as a subscription agent for the first newspaper owned and operated by black Americans. Freedom’s Journal was published weekly in New York City beginning in 1827, the same year slavery ended in New York State.2

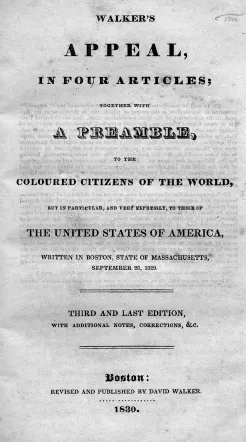

In September 1829, Walker published his momentous Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World. He wrote in the preamble to the lengthy pamphlet, “We (coloured people of these United States) are the most degraded, wretched, and abject set of beings that ever lived since the world began.” In four “articles” or essays based on his observations of black life in both Northern and Southern states, Walker described the miserable lives of both enslaved and free African Americans and argued that race-based slavery was the cause of Northern racial discrimination. He accused whites of ignoring the supposed self-evident truths of the Declaration of Independence and urged them to compare its language with the “cruelties and murders inflicted by your cruel and unmerciful fathers and yourselves on our father and on us.” He also warned whites of the consequences if his words were not heeded: “And wo, wo, will be to you if we have to obtain our freedom by fighting.”

First page of David Walker’s Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World. Courtesy of the University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Copies of Walker’s Appeal traveled quickly throughout black communities across the nation even though enraged Southern slaveholders persuaded their state governments to ban it and impose harsh penalties on those possessing or circulating it. Demand was so high that Walker published three editions within a few months. Unfortunately, he died on August 6, 1830, likely of tuberculosis, although rumors abounded that pro-slavery sympathizers had murdered him.

WILLIAM LLOYD GARRISON AND THE LIBERATOR

In the same year that Walker published his Appeal, William Lloyd Garrison came to Boston to deliver his first public antislavery speech. Garrison, who was born in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1805, had apprenticed at a newspaper in his hometown, where he honed his skills as both a debater and a printer. In 1828, he met Benjamin Lundy, a Quaker abolitionist and publisher of a Baltimore weekly called The Genius of Universal Emancipation. Lundy had organized an antislavery association in 1815 and started his newspaper in 1821. Many early abolitionists were Quakers, since slavery contravened the Quak...