- 158 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

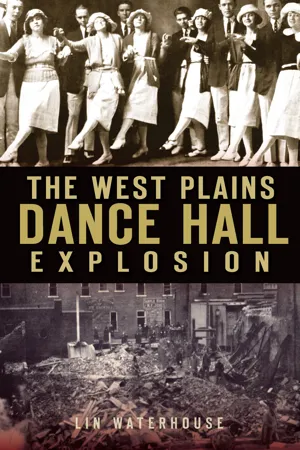

West Plains Dance Hall Explosion

About this book

The real-life mystery of a catastrophic blast in 1920s Missouri that killed dozens at a Friday night dance and shattered an Ozark town.

One rainy night in 1928, a crowd, many of them the sons and daughters of prominent local citizens, gathered for a weekly dance held at Bond Hall. The explosion that occurred as midnight approached transformed Bond Hall into a raging inferno, left thirty-nine dead, and sparked feverish national media attention and decades of bitterness in the Missouri Ozark town. And while the story inspired a popular country song, the firestorm remains an unsolved mystery.

In this first book on the notorious catastrophe, Lin Waterhouse presents a clear account of the event and its aftermath that judiciously weighs conflicting testimony and deeply respects the personal anguish experienced by parents forced to identify their children by their clothing and personal trinkets. Based on extensive research into archival records and illustrated with numerous photos, this is a fascinating account of a heartbreaking disaster and the town it tore apart.

One rainy night in 1928, a crowd, many of them the sons and daughters of prominent local citizens, gathered for a weekly dance held at Bond Hall. The explosion that occurred as midnight approached transformed Bond Hall into a raging inferno, left thirty-nine dead, and sparked feverish national media attention and decades of bitterness in the Missouri Ozark town. And while the story inspired a popular country song, the firestorm remains an unsolved mystery.

In this first book on the notorious catastrophe, Lin Waterhouse presents a clear account of the event and its aftermath that judiciously weighs conflicting testimony and deeply respects the personal anguish experienced by parents forced to identify their children by their clothing and personal trinkets. Based on extensive research into archival records and illustrated with numerous photos, this is a fascinating account of a heartbreaking disaster and the town it tore apart.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

INVESTIGATION

FACTS, RUMORS AND THE WRATH OF GOD

Officials wasted no time in appointing a coroner’s jury to investigate the explosion at Bond Hall and the deaths of thirty-eight people and injuries to at least twenty-one others. (Elbert White would die within a week, bringing the final death total to thirty-nine.) Coroner T.R. Burns of Willow Springs, Missouri, empanelled six prominent citizens of West Plains on Saturday morning, April 14, while recovery workers were still combing through the smoking ruins.

Burns recruited Charles Richard Bohrer, Dr. S.G. Dreppard, H. Thurman Green, E.E. McSweeney, Clarence C. McCallon and Samuel J. Galloway to hear the evidence surrounding the explosion. The distinguished jury met in the offices of Police Judge George Halstead.

Charles Bohrer was appointed foreman of the group. A pharmacist and drugstore owner, he was part of a pioneer family that had produced several generations of doctors and druggists in West Plains. Dr. S.G. Dreppard was a veterinarian, H. Thurman Green owned a motor garage, E.E. McSweeney was the district manager for the Standard Oil Company and Clarence C. McCallon was proprietor of the Cash Clothing Company. The last member of the panel, Samuel J. Galloway, had been elected as the representative from Howell County to the state legislature in 1922.

Will H.D. Green, the forty-four-year-old prosecuting attorney for Howell County, attended West Plains schools before he studied law under his father, Judge H.D. Green. He was admitted to the bar in 1905. Green had headed up the “dry forces,” sometimes referred to as the “Church of Dry Workers,” in their successful campaign to drive the saloons from Howell County long before prohibition became the law. An elder in the First Christian Church, Green was a longtime president of the Howell County Sunday School Association. As a lawyer, he steadfastly refused to defend any person charged with violating the liquor laws or with a crime against a woman.

Witnesses were called before the panel on Saturday, Sunday, Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday (April 14 through April 18), sometimes testifying far into the night. Public pressure demanded that the coroner’s jury find the cause of the explosion and fire. If someone intentionally detonated the blast, the town wanted to know the perpetrator’s name.

The jury’s working hypothesis was that gasoline stored in the Wiser Motor Company below Bond Hall exploded, causing the holocaust. Because the science of forensic pathology was unknown in 1928, members of the coroner’s jury could consider only the testimony of contemporary experts on explosives and then call on their own common sense and experience to make a determination. The responsibility of identifying a specific culpable person or persons weighed heavily on them.

In a letter dated April 20, 1928, addressed to Mayor Harlin and the city commissioners, W.J. Orr of Springfield, an attorney for the Frisco Railroad who had investigated explosions for the railroad, offered information about the power of gasoline-fueled blasts. Orr wrote that only through “sad experience” had he gained knowledge about such explosions and that many of the safeguards thought to be sufficient in the storage and handling of gasoline were actually inadequate and sometimes dangerous. Orr noted that, although gasoline in liquid form is less dangerous than the vaporous form, “there is sufficient energy stored in 1 gallon of gasoline [to] lift the Woolworth Building in New York City about six inches off its foundation.” A mixture of gasoline vapors and air “will explode if there is not more than six percent of gasoline vapors in the mixture,” he wrote. It will not explode if the percentage of gasoline is less than 1.5 percent of the mixture. “When the percentage is between these two extremes, that is, when the mixture is not too rich or too lean, the mixture will explode.”

An article printed in the Springfield Daily Leader and reprinted in the West Plains Weekly Quill on April 26, 1928, quoted engineer and explosives expert Will F. Plummer. According to Plummer, “If there is a grain of compensation to be found in the West Plains disaster it may be that people will learn something of the dangerous explosive power of gasoline.” He described a situation in which gasoline fumes could have accumulated in the basement of the Ward Building, causing the explosion. However, the Ward Building had no basement. Plummer offered the following evaluation: “To wreck so completely such a building would take, I should say, 200 pounds of 60 per cent dynamite, more than could be handled secretly, or more nitroglycerin than was ever assembled. On construction work we are not afraid of dynamite. Its power is greatly overrated, but nobody knows the shattering force of gasoline.”

The members of the jury knew that gasoline was present in Wiser’s garage. Ray Fisher of the Standard Oil Company testified that he had leased a fifty-gallon gasoline pump tank to Wiser on the Wednesday prior to the explosion. The tank was on wheels and could be moved around the building. Leonard Fite, Wiser’s salesman, estimated that the tank held forty gallons of gasoline at the time of the explosion. He testified that the gasoline was used for employees’ personal use and to fuel cars being tested by prospective buyers. He believed that the tanks on all the cars parked in the garage were empty.

Small amounts of gasoline purchased by Wiser on the day of the explosion raised questions about his involvement in the blast. Raymond Tiner worked for the Standard Oil station in West Plains. On Friday morning at about 8:00 a.m., Tiner sold five gallons of gasoline to Wiser. Only after the explosion did he think that the sale was significant. Carter Johnson, a salesman who worked at Carac Davidson’s garage, testified that he loaned a gasoline storage can to Wiser on Friday just after noon. He said that Wiser often borrowed the can. Sanford Palmer, another employee of the Standard Oil station, testified to selling Wiser thirteen gallons of gasoline at about 12:30 p.m. on Friday. He pumped eight gallons into the tank of the Chevrolet coach that Wiser was driving and five gallons into a gasoline storage can, presumably the one borrowed from Davidson’s garage.

Thomas McCord, chief engineer for Texas Company in Oklahoma, worked as “an inspector of natural gas.” After examining the ruins on East Main Street, he testified before the coroner’s jury. He told the jurors that he had witnessed four large gasoline explosions and four small ones. He had also observed two nitroglycerin explosions. McCord stated that during an inspection of the explosion site, he found the fifty-gallon tank of gasoline in Wiser’s garage “intact.” He concluded that the detonation of the tank was not the cause of the blast. He testified that sixty gallons of gasoline, a generous estimate of the amount in Wiser’s garage, was insufficient to produce an explosion the size of the one that demolished the Ward Building. Only if all of the gasoline had evaporated into a confined location and then “had some pressure on it” would it have exploded. “From appearances,” he said, “I would think nitroglycerin or some explosives had caused it.”

Mr. Ridgeway testified that he operated Ridgeway Dry Cleaners on Walnut Street in a building situated between the back (south side) of the Adams Building and the north side of the Arcade Hotel. Ridgeway’s building sustained little damage. Only “the door and windows [were] blown out and the glass broken.” Ridgeway said that Fluid Stanoline was the primary medium used to clean clothing but that most dry cleaners also kept gasoline, chloroform, ether, acetone carbon and alcohol in small quantities. Although he had heard of gasoline explosions at dry cleaning establishments, none was as large as the one at Bond Hall.

When asked if he thought vapors from the gasoline in Wiser’s garage could have caused the explosion, he said, “Gasoline within itself is not explosive, but the vapor must be mixed with air and be heated enough to form some pressure before it can explode.” He noted that salesman Leonard Fite and mechanic Jim Jewell had both testified that the stove in the garage was inoperable. Therefore, based on the amount of gasoline believed to be present in the garage and the lack of a heat source, Ridgeway did not believe that the blast was due to a gasoline explosion.

The jury could not determine if gasoline vapors had been present in the Ward Building prior to the explosion. Mr. Pool in his rooms at the Arcade Hotel and Beverly and Hattie Owen in the Riley Building all reported smelling gasoline before the blast. However, Mrs. Hawkins in the Adams Building, Warren Blakley inside his creamery in the Riley Building and Mo Ashley arriving at the dance smelled nothing out of the ordinary.

Without another suspect, the coroner’s jury focused on Joseph Wiser, and within an hour of the burial of his remains on Sunday, the jury had ordered Wiser’s body exhumed for a formal autopsy. The jury was troubled by his injuries and burns because they appeared inconsistent with those of other victims. Richard M. Jones, Grover Klain and Haydon Morton, three of the four men who discovered Wiser’s body after the explosion, testified about its location and described its condition.

George Stapp, undertaker at the Davis-Ross Undertaking Company, where Wiser had been taken, testified about the condition of the body, and he stated that Wiser’s clothes were not torn or burned. “His hair seemed to be singed and full of dust and gravel,” he told the jury. “His face had a few small scars on it, and the burn on his face looked like acid burns, fiery red in color.”

Wiser’s lips were discolored black, which Stapp stated was normal for a deceased person. During his first examination, he noticed the fiery red color of Wiser’s skin, and Stapp stated that he had not washed or rubbed the face in any way to cause this coloration. Only on the man’s forehead were any burns evident, and Stapp believed that they were consistent with “powder” burns because they were spotted with a bluish-black color, not a solid burn. Stapp admitted that he had never seen burns like them in the past. Stapp further testified that Mr. Dryer, mortician from Thayer, removed Wiser’s clothing, and Stapp and Jim Bridges collected Wiser’s watch, a few papers that were in his clothing and thirty-one dollars in cash. They noted that they found no matches in his pockets.

Physicians Lee E. Toney and H. Thornburgh testified about their findings from the autopsy they performed on Wiser’s body on the Sunday following the blast.

Dr. Toney stated that he found “penetrating wounds on [the] left side of the chin in front about an inch deep, [and] found contusion [to the] right temple, [a] region which upon opening up showed a fracture probably [an] inch and a half long, [and a] half inch wide.” He testified to “considerable discoloration” to the body but assumed that it was “due to the epidermis being rubbed off by the undertaker.” Wiser’s hands were burned to about an inch above the wrists, and he sustained a compound fracture of the right leg midway between the ankle and the knee. Since the blood in Wiser’s temple wound was clotted, the doctor believed that the injury could only have been sustained while the man was alive. However, Dr. Toney believed a “lineal fracture of the skull to the right of the occipital protuberance” could have occurred after Wiser’s death, perhaps from flying debris or falling timbers, although it could have occurred prior to the explosion.

Dr. Thornburgh testified to “dissecting the scalp,” during which he

found [a] depressed fracture of the skull in the right temple region about one inch and half long extending from the interior of the right temple downward and forward to the outer angle of the right eye. The temple muscle was out underneath and full of blood clots. The skin over the fracture was not broken. Also, [he had] a fracture of the skull at the upper occipital bone, I judge two inches long. The right side of the face was discolored dark red, and this indicated that he had been burned by acid rather than fire. The color of the burns being much different from that on his hands. The eyebrows and lashes were entirely burned away. The right arm was bruised and contused. Midway between [the] knee and ankle, both bones [were] broken. Also, [I found] a wound on the chin about one inch and a half to the left of the median line.

A deep puncture wound on the chin extended to the bone.

Dr. Thornburgh testified that he believed that if Wiser had been inside the building and blown through the brick wall, he would have exhibited more broken bones. However, he agreed with a questioner that Wiser could conceivably have been blown out through an open door at the rear of the garage. The burns, he said, could be explained if Wiser had gasoline on his hands at the time of the explosion. In comparing the burns of Wiser to the burns of Ford dealer Robert Martin, the doctor said that Martin’s were much more severe. “The burns on the other person [Martin] were alike as to color and its effect on the skin while the burn on Wiser’s face was a perfectly smooth burn and left the surface of the outer layer of skin blistered red, bright red, and not a dark or blue color and not deeper than the outer layer.” Wiser’s hands, however, “both had the same marks as those who had been burned by gasoline flames.”

“Couldn’t these burns on his hands [have] been made by him having gasoline on his hands, and when the explosion went off, burned his hands in that manner?” asked a questioner. Dr. Thornburgh answered in the affirmative.

Thornburgh told the jurors that he knew that nitroglycerin was made from ingredients that could be purchased at any drugstore and mixed by anyone who understood explosives. Although he had previously seen carbolic acid injuries and other types of acid burns, he had not seen any burns like the ones on Wiser’s face. He did not care to give an opinion about what might have caused the burns.

When asked for his opinion about how Wiser’s hands could have been blistered to the wrists but his face marked only with “very peculiar red spots,” explosives expert Thomas McCord admitted that he had never seen burns like that, but he theorized that Wiser’s “hands [could have been] in gasoline [when it] ignited and burned his hands.”

Initially, Wiser’s burns troubled the jurors, but after visiting one of the survivors in the hospital, they believed that they understood the differing patterns of injuries. On April 26, 1928, the West Plains Weekly Quill reported that the jury had visited Christa Hogan Hospital to view the face of Lewis Achuff (also spelled “Acuff ”), who had been dancing in the hall at the time of the explosion. According to the Quill, his face was “burned in identically the same manner, indicating that he came in contact with a sudden flash of flame or heat before he escaped.” The panel concluded that Wiser’s burns were “flash burns” that resulted from one quick flash of flame or heat instead of the steady heat that had seared so many of the other victims.

One aspect of Dr. Toney’s testimony caught the attention of the jury. Toney’s belief that Wiser could have sustained the skull fracture prior to the explosion raised the possibility that he might have been attacked by “yeggmen,” a term of the time for burglars or robbers. The panel considered that one or more of the men seen inside the garage with Wiser that night could have attacked the garage owner, who was rumored to have made substantial profits from his telephone business. The jurors theorized that such attackers might have set a fire to cover their crime and that the fire ignited the explosion.

Several witnesses placed Wiser in his garage on that evening, including Arnold Merk, who testified to seeing two men inside Wiser’s garage at about 10:30 p.m. Night constable Els Seiberling also reported seeing a man in the vicinity of Wiser’s garage at about 11:00 p.m. The man got into a Ford roadster and drove west on East Main Street. “It seemed he was in a hurry,” Seiberlin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Dancers

- West Plains: The Gem City of the Ozarks

- Life on East Main Street

- J.M. “Babe” Wiser: Man at the Center of the Firestorm

- The Dance

- Explosion!

- Horror and Heroics

- Rest in Peace: Burials and Memorials

- Investigation: Facts, Rumors and the Wrath of God

- Legalities and Indignities of Death

- The Community Rebuilds

- Consequences of Tragedy

- Beyond the Trauma

- Old Gossip and New Theories

- Epilogue

- Victims of the Bond Hall Explosion

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access West Plains Dance Hall Explosion by Lin Waterhouse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.