eBook - ePub

Stonewall Jackson's 1862 Valley Campaign

War Comes to the Homefront

- 257 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Stonewall Jackson's 1862 Valley Campaign

War Comes to the Homefront

About this book

Virginia's Shenandoah Valley was known as the "Breadbasket of the Confederacy" due to its ample harvests and transportation centers, its role as an avenue of invasion into the North and its capacity to serve as a diversionary theater of war. The region became a magnet for both Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War, and nearly half of the thirteen major battles fought in the valley occurred as part of General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's 1862 Valley Campaign. Civil War historian Jonathan A. Noyalas examines Jackson's Valley Campaign and how those victories brought hope to an infant Confederate nation, transformed the lives of the Shenandoah Valley's civilians and emerged as Stonewall Jackson's defining moment.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stonewall Jackson's 1862 Valley Campaign by Jonathan A Noyalas,Jonathan A. Noyalas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

“EMPLOY THE INVADERS

OF THE VALLEY”

By the first week of March 1862, anxieties had reached a fevered pitch in the heavily pro-Confederate community of Winchester, Virginia, as the inhabitants received news of an advancing Union army from Harpers Ferry—about 35,000 strong—under Major General Nathaniel P. Banks. “Quite a number of our people are leaving town,” noted a resident of Winchester on March 3, “frightened almost to death of the Yankees, that they will come and catch them.”3 As many of Winchester’s Confederate civilians evacuated the town, General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson began preparations to secure the safety of his small Confederate force of about 3,500 troops. Jackson ordered his army’s commissary and quartermaster stores moved south to Strasburg.4 Jackson also took measures to secure the safety of his wife, Mary Anna, who had been with her husband in Winchester since December. On March 3, Jackson sent Mary Anna to Strasburg, where she could board a train that would carry her farther south. “Early in March, when he found that he would be compelled to retire from Winchester,” Mary Anna recalled of her husband’s decision, “although his heart was yearning…he thought it was no longer safe for me to remain, and I was sent to a place of safety.”5

Four days after Jackson’s wife departed Winchester, Banks’s force moved to within four miles of Winchester’s outskirts, where they encountered Confederate cavalry from Colonel Turner Ashby’s command. After a small skirmish, Banks withdrew his army toward Bunker Hill. While Ashby’s troopers pushed Banks north, Jackson placed his army in defensive positions several miles north of Winchester and dared Banks to attack. Banks refused to accept Jackson’s invitation. “I was in hopes that they would advance on me during the evening,” Jackson wrote to his wife, “as I felt that God would give us the victory.”6 Ashby’s audacity on the seventh, as well as Jackson’s willingness to offer Banks battle, “impressed” the Union commander “with the conviction that the Confederate force was much greater than it was in reality.”7

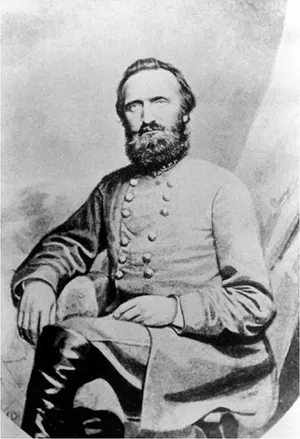

General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Courtesy of the Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society.

Despite the “excellent spirits” of Jackson’s army following Banks’s advance on March 7, Winchester’s Confederate civilians feared the imminence of Federal occupation.8 “The people are all crazy—perfectly frantic for fear this place will be evacuated and the Yanks nab them,” penned Winchester’s Kate Sperry on March 7.9 As tensions mounted over the next several days, Banks received information from a Unionist sympathizer in Winchester that Jackson would withdraw from Winchester. Additional reports confirmed that Jackson had a considerably smaller force than Banks.10 Confidently, Banks sent word to Washington, D.C., on March 8: “Our troops are in good health and spirits, eager for work…Our troops are…pressing forward in the direction of Winchester.”11

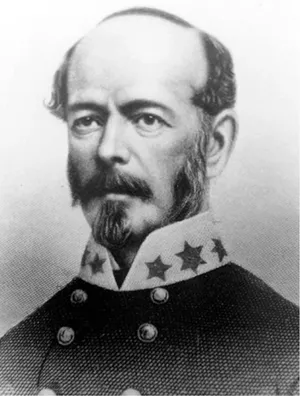

General Joseph E. Johnston. Courtesy of the Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society.

The same day that Banks informed his superiors that his men pressed “forward in the direction of Winchester,” Jackson wrote to his superior, General Joseph E. Johnston, that he greatly desired “to hold” Winchester.12 Additionally, Jackson implored Johnston for reinforcements. “The very idea of re-enforcements coming to Winchester would, I think,” Jackson informed his chief, “be a damper to the enemy, in addition to the fine effect that would be produced on our own troops.”13 The strategic situation, however, precluded Johnston from granting Jackson’s request. Johnston, whose army was in the process of withdrawing from Manassas Junction to Richmond’s defense, could ill-afford to offer any additional support to Jackson.14 While Johnston did not necessarily want Jackson to evacuate Winchester, Johnston believed that it was more important for Jackson to keep his army intact so that it could serve as a distraction to General George B. McClellan’s operation against Richmond. Johnston hoped that once Jackson withdrew from Winchester, he could “employ the invaders of the Valley, but without exposing himself to the danger of defeat, by keeping so near the enemy as to prevent him from making any considerable detachment to reinforce McClellan.”15

As it became more evident that Jackson would have to withdraw, he decided to arrest scores of area Unionists to protect his operational security. By some estimates, about 10 percent of Winchester’s population held Unionist sympathies. The reasons for these sympathies varied—some were transplanted Northerners, others disagreed with secession and slavery and a portion belonged to religious groups such as Quakers and Mennonites, who refused to side with the Confederacy.16 After a declaration of martial law on March 10, Jackson seized scores of male Unionists who lived in Winchester and the immediate surrounding area.17 Among the Unionists seized by Jackson was Winchester’s Charles Chase. Confederate soldiers entered the aged and infirm Chase’s home and ripped him from his sofa. “To take an old man lying sick on the sofa is outrageous,” recalled Chase’s daughter Julia.18

As Julia learned of the arrests of other Unionists, she could only write, “We are fallen upon fearful times, great many Union people have been put in the guard house.”19 Another area resident recalled that Jackson’s arrest of Unionist sympathizers “was the most humiliating sight…since the opening of the war. Gray-haired and prominent citizens marched like felons through the streets, tramping through mud and rain between files of soldiers.”20

Despite the measures that Jackson took to secure his army for a withdrawal, Jackson maintained some degree of hope that his subordinates would support him in his desire to not relinquish Winchester without a fight. On the evening of March 11, Jackson dined at the home of Reverend Robert Graham on Braddock Street. When Jackson arrived for dinner, Reverend Graham recalled that Jackson was “all aglow with pleasant excitement because of the splendid behaviour of the troops, and their eagerness to meet the enemy.”21 Following dinner, Jackson left Graham’s and proposed a surprise attack on the enemy that night. His subordinates disapproved and instead urged Jackson to withdraw. Prudence intervened and Jackson agreed to pull out.22 Although Jackson opted to heed the advice of his brigade commanders, he “was bitterly distressed and mortified,” noted Reverend Graham, “at the necessity of leaving the people he loved dearly.”23 Amid his disappointment that evening, Jackson learned a valuable lesson from the experience of his war council: to never hold one nor ask for his subordinates’ opinions again. An officer from Jackson’s command noted that his council of war in Winchester was “the first and last time…that he ever summoned a council of war.”24

Once Winchester’s Confederate citizenry received confirmation of Jackson’s withdrawal, they took measures to secure their property and prepare for what would become the first of many Union occupations. “From twelve till after one, we were very busy,” recorded the staunch Confederate Mary Greenhow Lee, “putting in place of safety silver, papers, sword, flags, with my clothes, war letters, &c.”25 Other Confederate civilians in Winchester secured not only personal possessions but also bade farewell to loved ones who served in Jackson’s command. Cornelia McDonald recalled that on the night of March 11 “there were hurried preparations and hasty farewells, and sorrowful faces turning away from those they loved best, and were leaving, perhaps forever.”26

As Jackson’s army marched south, Banks prepared to occupy Winchester. Banks approached cautiously and methodically. An artillerist in Banks’s army stated that the army had to move “slow for fear of a fight.”27 The fortifications constructed by Jackson during the war’s early months also presented an imposing sight to Banks’s troops. “Several earthworks were observable, and we looked for a great battle,” recalled General Alpheus Williams, one of Banks’s division commanders. “It was an exciting sight.”28 Federal pickets inched their way toward the earthworks but found them vacant. While Banks’s army occupied the earthworks, Winchester’s mayor, John B.T. Reed, moved out to meet the Federal soldiers and surrender the town. With the town’s surrender complete, the Federals marched into Winchester triumphantly.

Initially, the reception of the Union army by the citizens proved optimistic to Banks’s troops. One of Banks’s staff officers, David Hunter Strother, noted that as the Union army entered town, he “saw a group of men, women, and children waving handkerchiefs and welcoming us with every demonstration of delight.” Interspersed throughout the crowd were area slaves and free blacks who looked upon Banks’s men as potential agents of freedom.29 Unionists and area African Americans reveled in the occupation. “Glorious news,” confided Unionist Julia Chase to her journal on March 12.

General Nathaniel P. Banks. Courtesy of the author.“The Union Army took possession of Winchester today and the glorious flag is waving over our town.”30

While Unionists and African Americans applauded the sight of Union soldiers, the town’s overwhelming Confederate majority loathed the spectacle before their eyes. Most citizens could not even bring themselves to come out of their homes to watch Banks’s troops march into town. “The town during the entrance presented a sad and sullen appearance,” noted John Peyton Clark. “Many of the houses of the citizens were entirely closed, few, perhaps none of the respectable portion of the town were conspicuous on the street.”31 Mary Greenhow Lee lamented, “All is over and we are prisoners in our own houses.” Despite her melancholy tone, Mary Lee believed that it had been for the best, as she knew deep down inside that Jackson would not have been able to defeat Banks’s army. “I remembered how thankful I was,” ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. “Employ the Invaders of the Valley”

- Chapter 2. “Defeated, but not Routed nor Demoralized”

- Chapter 3. “God Blest Our Arms”

- Chapter 4. “The Victory Was Complete and Glorious”

- Chapter 5. “Like Mad Demons”

- Chapter 6. “This Campaign Made the Fame of Jackson”

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author