eBook - ePub

Defending South Carolina's Coast

The Civil War from Georgetown to Little River

- 163 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Defending South Carolina's Coast: The Civil War from Georgetown to Little River, area native Rick Simmons relates the often overlooked stories of the upper South Carolina coast during the Civil War. As a base of operations for more than three thousand troops early in the war and the site of more than a dozen forts, almost every inch of the coast was affected by and hotly contested during the Civil War. From the skirmishes at Fort Randall in Little River and the repeated Union naval bombardments of Murrells Inlet to the unrealized potential of the massive fortifications at Battery White and the sinking of the USS Harvest Moon in Winyah Bay, the region's colorful Civil War history is unfolded here at last.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Defending South Carolina's Coast by Rick Simmons in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

THE NORTH ISLAND, SOUTH ISLAND AND CAT ISLAND FORTS

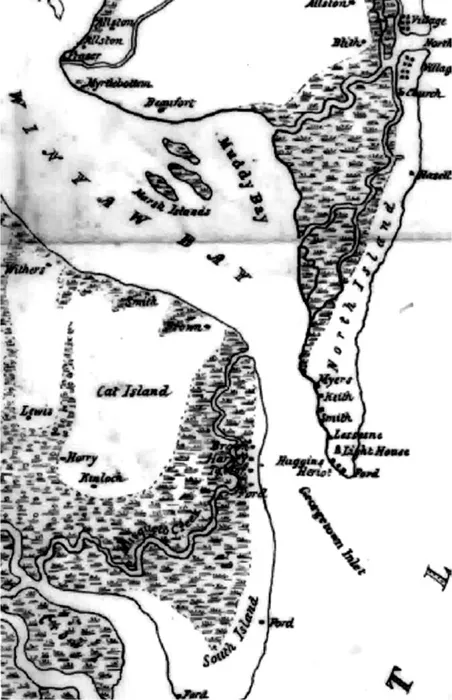

Even before the Civil War, those familiar with the long stretch of South Carolina coast from Georgetown to Little River were aware that there were certain key positions that would be extremely attractive to invading Union forces should a war begin. Both Little River and Murrells Inlet had anchorage enough that they could house ships laden with goods coming in and going out, and thus those inlets could be used by Union ships, as well as by the blockade runners upon whom the economic viability of the struggling South depended. The most important area of the coast by far, however, was centered on Winyah Bay. Not only was it the location of the district’s largest city in Georgetown, but the bay was also large enough that it could harbor the entire United States Navy in 1861. In addition, the bay provided access to the Black, Pee Dee, Waccamaw and Sampit Rivers, and the mouths of the North and South Santee Rivers were just below Winyah Bay as well. Consequently, whoever controlled the bay controlled Georgetown, as well as the surrounding rivers, and, by extension, also determined the viability of the local rice economy.

The Georgetown area was the largest producer of rice in America and the second-largest rice-producing area in the world, but without Winyah Bay and control of the rivers, the rice would be left to rot in the fields. Though those events would eventually transpire, in 1861 the Confederacy was determined to protect the area at all costs. In order to do so, an extensive series of fortifications was constructed in the area, the largest and most important of which were the forts on North, South and Cat Islands on Winyah Bay.

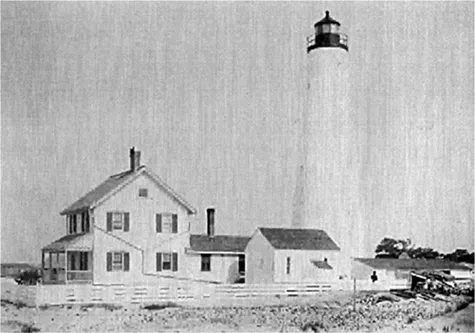

The North Island Lighthouse. Photograph by the author.

When the Ordinance of Secession was signed in Charleston on December 20, 1860, it was the climax to a long-developing series of events that was, to some people, inevitable. Even before the official outbreak of hostilities, companies of local militia were formed and camps of instruction were established from Georgetown to Little River. In the months that followed the signing of the ordinance, more and more companies of local militia were raised and likewise tendered their services to the state. Camps of instruction sprang up at a number of locations along the Strand, and these camps were more ubiquitous than any other form of military installation during the war. Today, only names exist for many of these camps, and names alone provide few clues about their locations. While we know that Camp Marion was about two miles out of Georgetown at White’s Bridge, Camp Norman was on North Island near the lighthouse, Camp Lookout was on the coast in Murrells Inlet and Camp Magill was on the Waccamaw River, in other cases only names that shed little light on these camps’ locations remain. Camp Trapier (probably at Frazier’s Point later in the war), Camp Waccamaw, Camp Chestnut, Camp Harlee, Camp Middleton and others now exist as no more than footnotes in the few remaining records from the period.

In addition to the camps of instruction, even before the war the government of South Carolina encouraged citizens and municipalities to build batteries in coastal areas that were important and vulnerable. In a dispatch of May 17, 1861 (almost a full month before the hostilities officially began), from General P.G.T. Beauregard to Captain F.D. Lee of the Corps of South Carolina Engineers, Beauregard instructed Lee to head to Georgetown to inspect sites for the forts that would be built along the coast. Beauregard noted that there were already two batteries at Georgetown, but he wanted the guns at the batteries consolidated into one fort (this was never done, and within a year, there would be one additional fort there, not one fewer). Defenses were planned for the mouths of Little River, Murrells Inlet, the North and South Santee and on North Island, South Island and Cat Island.

Lieutenant Louis F. LeBleux supervised much of the engineering work in the area, and earthworks were built at a number of key locations around Winyah Bay. Though often the armament was inadequate, early in the war the Federal navy didn’t seem to be willing to risk testing the range of the Confederate guns very often. After the Federals captured Port Royal on November 7, 1861, it was clear that the fortifications along the coast needed improving in order to prevent other key areas from falling into Federal hands. A new department commander was appointed to supervise the construction of defenses along the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia and northern Florida, and the man chosen was General Robert E. Lee.

Although Lee’s fame as a military commander would come on the battlefields of Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania later in the war, in 1861 he was relatively unknown to the general public. Lee, however, was an excellent engineer and was well known for his ability to plan and construct defenses. Lee knew that areas such as Horry and Georgetown Counties were important agriculturally as well as strategically, and in this knowledge he had a subordinate who was in full agreement. As Colonel Arthur Middleton Manigault, in charge of the Georgetown-Horry district, wrote:

It was a matter of great importance that this region of the country should [be] preserved, for a very large portion of the rice crop of the south [is] grown on the two Santees, and on the rivers emptying into Winyah Bay,—the Pee Dee, Waccamaw, Sampit, and Black Rivers. The additional means it furnishe[s] of subsistence to our armies, [is] a matter of great consequence…even at a considerable cost.

Lee’s first task was to improve the coastal defenses, a task that he would have to do with considerably fewer troops in the area. Many troops in the militia that had been stationed along the coast had been discharged, some had their terms of enlistment expire and did not reenlist, many were transferred and many were ill and unfit for duty. In December, Manigault reported that he had fewer than one thousand men on duty in the district (just months before, Manigault had an aggregate of almost three thousand men in the district, including twenty-nine companies of infantry, six companies of cavalry and one company of artillery). In spite of these shortages of manpower, Lee had Manigault reassign his troops, improve existing fortifications and, in some cases, build new ones. Area forts outside of the Winyah Bay area included Fort Ward in Murrells Inlet and Fort Randall in Little River, and it was probably at or about this time that the earthworks at Laurel Hill and Richmond Hill were built.

In Winyah Bay, the three most important positions were at North Island, South Island and Cat Island.

THE NORTH ISLAND LIGHTHOUSE AND FORT ALSTON

North Island is undoubtedly the most colorful and arguably the most historically important area along the Grand Strand. Up until the early nineteenth century, the island was a resort area for planters seeking to escape the heat of their inland residences, much like Pawleys Island to the north. North Island is much more inaccessible than Pawleys Island, however, and today it can be reached only by boat. After a hurricane in 1822 destroyed most of the houses on the island, it was used much less often as a resort; from the Civil War on, it has frequently been in a state completely devoid of human habitation, as it is today.

Prior to the Civil War, perhaps the most important historical event to take place on North Island was the landing of the Marquis de Lafayette and Baron De Kalb on the island on June 13, 1777. Lafayette and De Kalb landed a small boat in search of a pilot for their ship so that they could eventually join George Washington. They were brought to the North Island summer home of Benjamin Huger, where they stayed for two days before proceeding to Charleston. Today, a historical marker on Highway 17 commemorates that event.

North Island is littered with brick fragments from the homes that existed before the Civil War. These bricks are just beyond the dunes on North Island, on the Winyah Bay side of the island. Photograph by the author.

This Mill’s Atlas map of 1825 shows the proximity of North, South and Cat Islands and establishes the degree to which forts at those locations would have controlled access to Winyah Bay. Library of Congress Map Collection.

More noteworthy and more important in terms of its bearing on the Civil War was the construction of the North Island Lighthouse, which is the oldest existing lighthouse in South Carolina and one of the oldest in the United States. Built on a tract of land donated by the planter and patriot Paul Trapier in 1789, the lighthouse was begun in 1799 and completed in 1801. This seventy-two-foot-tall structure, which was built of cyprus and burned whale oil to light its lamp, was destroyed in a storm in 1806. A second lighthouse was built on the spot by 1811, and this structure was the base for many military operations, both Union and Confederate, throughout the war.

Even early in the war, it was clear that the Georgetown lighthouse was not only important strategically but also because it provided a lookout post that was undoubtedly the highest accessible point on the coast. As a result, the main duty of troops stationed at the lighthouse was to watch for ships. As early as February 1861, mention of a redoubt named Fort Alston appears as being located on North Island, and at the beginning of the war it appears that Company D and Company B of what would become the Tenth South Carolina Regiment were stationed there in nearby Camp Norman. Unlike the other Winyah forts, no specific inventory of artillery seems to exist, but a letter dated February 22, 1861, from John R. Beaty of the Tenth South Carolina Regiment, mentions that “the cannon at Fort Alston are firing and the balls pass down the Bay…they are practicing range to be ready…it has an ugly sound but I suppose I can get used to it.”

As for conditions on the island, Beaty wrote, “It is a bleak barren row of sandhills exposed to the ocean on one side and Winyah Bay on the other… covered with a thick grove of pine and palmetto, very hilly and broken and a most capital place for riflemen to skirmish.” There was also, for a time in 1861, a small fort on the north end of the island (at one time companies A, E, H and K of the Tenth Regiment were alternately stationed there), though it appears that this fort did not permanently mount any artillery and was only occasionally armed with the mobile fieldpieces of the Waccamaw Light Artillery. In April 1861, Major William Capers White notes having posted Captain Thomas West Daggett, two officers and twenty-six men of the Waccamaw Light Artillery on coast watch on North Island; thus, the fort on the north end of the island may have been simply a base with some earthworks but not a major fortification.

There was clearly a need for forts on the island, not only to protect the bay but also to deal with the wrecked ships—blockade runners and warships—that were constantly running aground on the island. On November 2, 1861, the Union steamer Osceola foundered off of Georgetown, and two boats of captive crewmen were detained on North Island. On December 24, 1861, the USS Gem of the Sea attacked a beached runner, the Prince of Wales, there. That night, Colonel Manigault was informed that one thousand to fifteen hundred Union troops had landed on North Island, and though this proved to be false, the next day a Union transport ship loaded with troops passed so close to North Island that the soldiers onboard could clearly be seen by the Confederates.

As this undated early twentieth-century Coast Guard photo shows, at one point there were pleasant and obviously habitable quarters on North Island for the lighthouse keepers. Today, all of these structures, save the lighthouse, have disappeared, and the area is overgrown. U.S. Coast Guard photograph.

Consequently, the North Island fort was important in that it sustained a Confederate presence on the island. However, when General Lee was transferred to more important theatres of the war, his successor, General John Pemberton, who took command on March 14, 1862, made the unpopular and controversial decision to withdraw all Confederate troops and abandon the forts in the area. He wrote to Colonel Manigault on March 25, 1862:

Having maturely considered the subject, I have determined to withdraw the forces from Georgetown, and therefore to abandon the position…You will proceed with all the infantry force under your command to this city, Charleston, and report to Brigadier General [Roswell] Ripley.

In addition to the troop withdrawals, most of the area forts, all of which were nearly finished, were to be abandoned. Their guns were removed, transferred to railroad cars and shipped to Charlest...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter One. The North Island, South Island and Cat Island Forts

- Chapter Two. “I Deemed it Prudent to Surrender rather than Have the Men All Shot Down”: Fort Randall and Operations at Little River

- Chapter Three. The Plantation War: Rice, Salt and Contrabands

- Chapter Four. “He Was Hung Immediately after Capture”: The Assault on Murrells Inlet

- Chapter Five. Blockaders and Blockade Runners

- Chapter Six. “Well-constructed, and Very Formidable”: Battery White, Fort Wool and Frazier’s Point

- Chapter Seven. “A Vessel of War of Some Magnitude”: The Confederate Gunboat CSS Pee Dee

- Chapter Eight. The Eventful Final Days of the USS Harvest Moon

- Appendix. A Timeline for Civil War–related Events from Georgetown to Little River

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author