- 163 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hidden History of Rhode Island and the Civil War

About this book

The smallest state to defend the Union and one far from the battlefront, Rhode Island's stories of the Civil War are often overlooked. From Brown University's John M. Hay, later to become Lincoln's assistant secretary, to the city of Newport's role as the temporary headquarters for the U.S. Naval Academy, the Civil War history of the Ocean State is a fascinating if little-known tale. Few know that John Wilkes Booth visited Newport to meet his supposed fiancee just nine days before he assassinated President Lincoln. The state also contributed several high-ranking officers to the Union effort and, more surprisingly, two prominent officers to the Confederacy. Remarkably, Kady Southwell Brownell also openly served as a soldier in a Rhode Island infantry regiment. Join author Frank L. Grzyb as he investigates Rhode Island's rich Civil War history and unearths century-old stories that have since faded into obscurity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hidden History of Rhode Island and the Civil War by Frank L Grzyb in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

IN THE BEGINNING

MISCELLANY

Officially called the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, residents of Little Rhody (as it is affectionately referred to by many inhabitants) always seemed to have their own mindset. Banned from the Massachusetts Bay Colony because his religious views substantially differed from the Church of England, Roger Williams founded the colony of Rhode Island in 1636. His religious doctrine was based on the premise that religion and government could peaceably coexist. The doctrine of “separation of church and state” (at the time, such thoughts bordered on blasphemy) is the foundation that we as Americans enjoy today: religious tolerance and freedom.

Roger Williams died in 1683, but his ideals lived on. Nearly a century later, colonists faced another challenge: the right of self-determination. Principals from most of the colonies met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to establish their rights over British occupation and tyranny. At least two conventions met before a plurality was achieved. On September 17, 1787, a constitution was drafted, but before the document could become official, it required the approval of nine of the original thirteen colonies. Delaware became the first to ratify the Constitution on December 7, 1787. Although Rhode Island was the first state to declare its independence from Great Britain on May 4, 1776, when the time came to send delegates to the Constitutional Convention, it balked, not once but three times. In March 1788, Rhode Island put the issue up for public referendum. The vote failed. When advised that the state would be treated no different than any other foreign government, Rhode Islanders, now feeling cornered, convened a ratification convention. This time, the measure was approved, but only by a slim two-vote margin. On May 29, 1790, Rhode Island became the last state to ratify the Constitution.

Although Rhode Island was the smallest state in size during the Civil War, it never suffered an inferiority complex. Rhode Island’s contributions to the war effort were many. Helped along by hardworking immigrants, the state had developed a large industrial base, especially in the textile industry that greatly aided the Union war effort. Rifles and cannons were also produced in abundance. And when President Lincoln called for troops to quell the rebellion, Rhode Island was the first to respond on April 18, 1861, with an infantry unit and a battery of artillery: the First Regiment Rhode Island Detached Militia and the First Light Battery Rhode Island Volunteers. In the ensuing years, the state mustered eight infantry regiments, three cavalry regiments, nine batteries of artillery and three heavy artillery regiments. All were composed predominantly of Rhode Island men.

When the war ended, from a population of about 175,000, Rhode Island had sent 25,236 civilians off to war, sacrificing 1,685 (491 killed in action) of its brave lads to preserve the Union. Soldiers from the state had been present at all the major battles and numerous skirmishes less known today; 16 received the Medal of Honor, 9 of whom were artillerymen. Of the 9, 7 were awarded to members of Battery G, First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery, for extraordinary bravery at Petersburg (no U.S. Army battery since has received as many for a single day’s engagement). Amazingly, Rhode Island supported Lincoln’s repeated calls for troops on every occasion, and when the draft was enacted, it never resorted to conscription, having achieved its quota on each occasion.

Perhaps not as well known, Rhode Island was the first state to issue a call for enlistment of black soldiers in the Union army. The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) was made up of not only Rhode Islanders but also black men from other free states.

REVEREND OBADIAH HOLMES AND HIS UNIQUE GIFT TO THE WAR EFFORT

The Rhode Island connection began with Reverend Obadiah Holmes back in the early seventeenth century. Although Reverend Holmes had been dead and buried long before the first shots were fired on Fort Sumter, his legacy continued throughout the Civil War—and, for that matter, for years thereafter.

Who was this man, and what was his connection to our nation? The answer is straightforward: although Reverend Holmes’s contribution was significant, his link to the Civil War remains largely unknown. Even in Middletown, Rhode Island, where his role is noted on a small bronze tablet placed within yards of his grave, only a scant few know of his life’s work, pious deeds and lasting gift. In fact, in the mid-twentieth century, a wreath was laid and a special tribute paid at the small family cemetery where his remains have rested for several centuries. Witnessed by local dignitaries, Major General Ulysses S. Grant III, grandson of General Ulysses S. Grant, had the honor of placing the wreath next to the severely weathered, barely legible slate headstone.

Obadiah Holmes was born in 1606, 1607 or 1610, depending on which account a person wishes to believe. He came to the colonies after marrying Catherine Hyde on November 20, 1630. The ceremony had taken place at Manchester’s Collegiate College Church in Lancashire, England. Crossing the Atlantic in 1638 proved to be a long and grueling affair, as he and his wife encountered rough seas and inclement weather throughout their voyage. Not long after landing, the couple traveled north and settled in the small town of Salem. While residing there, Reverend Holmes was admitted to the Church of England. To earn a stable existence, he started the first window glass foundry in the colonies while continuing to pursue his religious calling. But after facing unyielding religious persecution and his inability to curb his outspoken demeanor when it came to his spiritual beliefs, especially those that differed substantially from the Church of England, he was excommunicated from the church. The chastising forced him to move some forty miles south to a small town called Rehoboth.

After preaching his puritanical ideals to a group of locals, he was ordered to abstain from such ministry. Not to be deprived of his convictions and his desire to promote his faith without outside interference, Obadiah and his wife moved again, this time only a short distance to the colony of Rhode Island, where religious teachings such as his were better tolerated. But soon, more problems arose. In 1651, Reverend Holmes decided to return to Massachusetts to help an old man with an undisclosed illness. Unfortunately for Reverend Holmes, he and his two-man party made the mistake of conducting a religious service in the man’s home. It was not long before local spiritual leaders got wind of the heresy and placed him under arrest. Fined thirty pounds, Reverend Holmes refused to pay, preferring the dire consequences of a public flogging.

The United Baptist Church stands on the site where Reverend Homes founded his first ministry in the colony of Rhode Island. Photo by the author.

On September 5, 1651, in Boston, Massachusetts, Reverend Holmes, after being tied to a whipping post, took the thirty lashes with neither a groan nor a scream. It was not an easy punishment at the hands of the punisher, who was said to flail a three-cord whip using both hands simultaneously to achieve the full force of each blow. Accounts note that between lashes, Reverend Holmes continued to preach his beliefs to the crowd. Although the flogging swiftly curbed his strength, he was heard to say, “You have struck me as with roses.” After paying for his indiscretions with a pound of flesh, Reverend Holmes was forced to remain in Boston until he recovered several weeks later. In the meantime, he ate his meals on his hands and knees like a dog until the cuts began to heal and the pain in his back subsided. His suffering so impressed Bostonians that a Baptist church was founded there soon after his departure.

In 1652, and following in the religious footsteps of a colleague, Roger Williams, Reverend Holmes became the pastor of the First Baptist Church in Newport, Rhode Island. There he succeeded his friend and first pastor, Reverend John Clarke. For some thirty years, his ministry continued as his church grew in size and stature.

During his life, Reverend Holmes fathered nine children and forty-two grandchildren. When he passed away in 1682, he left a legacy of spirituality for his children by instructing them to live their lives according to scripture and to “meet, support, strengthen, and reprove one another.”

Six generations passed before Reverend Holmes’s unique gift found its way to a person both adored as a saint and loathed as a devil, depending on which side of the Civil War one stood. What was the gift this humble and pious man bequeathed to a generation facing the worst war the United States ever experienced? Reverend Obadiah Holmes never knew and perhaps never envisioned that his genes would find their way into the body of one our nation’s greatest presidents: Abraham Lincoln. Indeed, Abraham Lincoln was his direct descendent.

For those interested in the lineage, this is how it came to pass:

• Obadiah Holmes (16??–1682) married Catherine Hyde;

• Their daughter Lydia Holmes (????–1693) married John Bowne (1530–1684);

• Their daughter Sarah Bowne (1669–1714) married Richard Salter (????–1728);

• Their daughter Hannah Salter (????–1727) married Mordecai Lincoln (1686–1736);

• Their son John Lincoln (1716–1788) married Rebecca Flowers (1720–1806);

• Their son Abraham Lincoln (1744–1786) married Bathsheba Herring (?) (1750–1836);

• Their son Thomas Lincoln (1778–1851) married Nancy Hanks (1784–1851); and

• Their son Abraham Lincoln married Mary Todd. Years later, Lincoln became the sixteenth president of the United States of America.

Plaque imbedded in the ground at the Rhode Island Historical Cemetery in Middletown, Rhode Island, that commemorates Reverend Holmes. Photo by the author.

Did Abraham Lincoln know of his ancestry and New England roots? It is doubtful. Lincoln once professed to not knowing who his grandfather was, much less having a Baptist minister in his family tree many generations removed.

For those curious, if given the opportunity to visit the town of Middletown, Rhode Island, on picturesque Aquidneck Island, it is worth a short detour from the center of the business district to see the Holmes Burial Ground, the official designation of which is the Rhode Island Historical Cemetery, Middletown, No. 19. Near the road is a small bronze plaque attached to a slab of granite that denotes Reverend Obadiah Holmes’s foremost accomplishments. His final resting place lies only yards away.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN VISITS RHODE ISLAND

Abraham Lincoln came to Rhode Island on three separate occasions—not as president of the United States, but undoubtedly with presidential aspirations in mind. In September 1848, Lincoln stopped in the capital city of Providence on his way to a Whig Party convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. After a short layover, he departed for New Bedford. Then, in 1860, and now a Republican, he made overnight visits to Rhode Island. Campaigning for the nation’s highest office was foremost in Lincoln’s mind, as was the opportunity to visit his son Robert, a student at prestigious Phillips Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire.

Initially, Lincoln planned to speak about the country’s most pressing issue of slavery to an audience in Brooklyn, New York. The talk was eventually moved from Brooklyn to Cooper Institute in Manhattan to accommodate a larger audience, which would include such notables as William Cullen Bryant, Horace Greeley and David Dudley Field. Knowing the difficult challenge that lay ahead in his campaign due to his limited political exposure outside the Midwest, Lincoln spent nearly three days honing his speech before actually giving it on February 27, 1860.

When Lincoln arrived at the institute, his physical appearance surprised many in attendance. He was unlike anything the spectators had imagined. An attendee described him thusly:

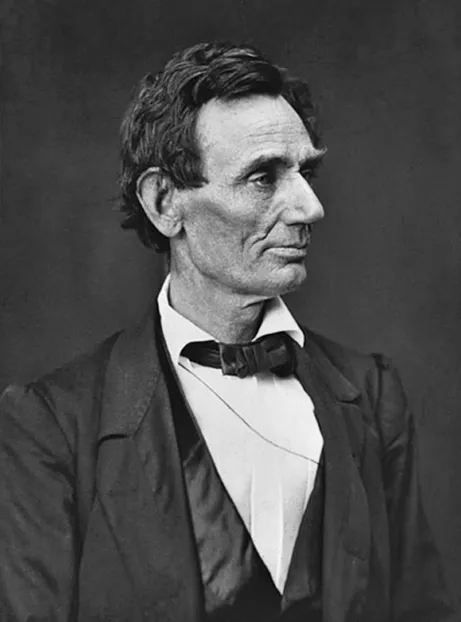

Mr. Lincoln was a tall man about 40 years of age, clothed in dark clothing with a black silk cravat, over six feet in height, slightly stooping as tall men sometimes are, with long arms, which he frequently moved in gesticulation, of dark complexion with dark almost black hair, with strong and homely features, with sad eyes, which moved in earnest argument or quiet humor, and then assumed a calm sadness.

Soon, however, his words overwhelmed the influential crowd. His speech that day became a classic and today is celebrated as “Lincoln’s Cooper Union Address.” With methodical reasoning, a persuasive argument and a no-nonsense delivery, his remarks catapulted him to national prominence in the days and weeks ahead. The American press enhanced his rising image with glowing articles about his talk. Arguably, his most memorable words that evening were given in his closing statement: “Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

The following morning, Lincoln departed Manhattan by train, passing northeast through Connecticut and into southern Rhode Island before arriving in Providence late in the afternoon. He was just in time for a dinner engagement at the homestead of Mr. John Eddy, a prominent Rhode Island lawyer and local Republican who had accompanied Lincoln on the train. Eddy had recruited Lincoln to speak in Providence while both were in New York. Hours later, Lincoln spoke to an audience estimated at 1,500 on the second floor of Railroad Hall at the northern end of the Union Passenger. (The 1848 building, once touted as the longest of such type in America, has long since been razed, and the Federal Courthouse at Kennedy Plaza is now situated on the site. A bronze plaque is visible on the building—the corner of Exchange Street and Fulton Street—commemorating Lincoln’s appearance.) Lincoln’s speech that evening was said to be a repeat performance of the previous evening. Unfortunately, the hall was not large enough, and many were turned away, although a contingent of students from Brown University did gain access. Among them was William Ide Brown. Five years later, while fighting for the Union, Brown was killed at Petersburg.

In early June 1860, photographer Alexander Hesler traveled from Chicago to Springfield, Illinois, to take Abraham Lincoln’s image. Library of Congress.

After an introduction by Honorable Thomas A. Jencks, Lincoln took the floor. His opening remarks alluded to items he had read in a newspaper while traveling by train to the city. The speech was slightly different then the speech he gave at Cooper Institute the previous evening, but according to local press, there appeared to be many similarities. His oration lasted two and a half hours, and unfortunately, no transcription of his talk has been found. As was to be expected, Lincoln’s words met with mixed reviews, depending on the political persuasion of the local press. The Providence Daily Journal, the Republican newspaper, commended his efforts, while the more conservative democratic newspaper, the Providence Daily Post, was less than kind. Neither commentary came as a surprise. By most accounts, gains were made by Lincoln that evening that swayed more citizens from Rhode Island to his side of the slavery argument: that he and his party were against the expansion of slavery in the territories and that slavery could not be defended by the U.S. Constitution.

Following his successful speech, Lincoln spent the remainder of the day at the home of his host, in a house located in a residential neighborhood on Washington Street. Mr. Eddy, a merchant and prominent lawyer in Providence, was the brother-in-law of Charles T. James, owner of a number of cotton mills and a former Democratic U.S. senator from the state (James’s exploits are covered later in another story). Meeting Mr. Eddy’s wife must have been a pleas...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I. In the Beginning

- Part II. The Excitement and the Reality

- Part III. The War Continues

- Part IV. War’s End

- Part V. The Legacy

- Part VI. Tributes in Bronze and Stone

- Part VII. Strange Happenings

- Part VIII. 150th Anniversary

- Resource Information and Author Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author