![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE SIREN SONG OF KENTUCKY

Chattanooga, Tennessee, shimmered in the summer heat on the last day of July 1862. The town and its surrounding ridges swarmed with Confederate troops as an army of thirty thousand men arrived by train and crowded in and around the town of two thousand residents. The buzz of activity broke through the oppressive temperatures.

The nexus of all this military commotion was the downtown hotel that served as headquarters for the Army of the Mississippi, as this incoming force was known. In an upstairs room, two Confederate generals were meeting that day to discuss options and plans. Seen side by side, the two men offered an interesting contrast—one tall and erect of bearing, while the other was shorter and more dour.1

The taller officer was Major General Edmund Kirby Smith, who commanded the Department of East Tennessee with headquarters in Knoxville. Kirby Smith was a native Floridian who brought a distinguished record to this meeting. At age seventeen, he had entered West Point and graduated in 1845 in the middle of his class. A veteran of the Mexican War, where he won two brevet promotions for bravery, he compiled a solid record as an Indian fighter in the 1850s. In 1861, he resigned from the U.S. Army and followed his native state into the Confederacy. At the First Battle of Manassas in July 1861, Kirby Smith’s brigade arrived last on the field and launched a smashing counterattack that started the Federal rout. Wounded in the action, he emerged, along with Brigadier General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, as a principal hero of the battle. He had come to East Tennessee in February 1862 with the dual mission of defending the area and holding down the restive pro-Union population. The job in Knoxville was an important but less glamorous post, especially compared to some of his contemporaries’ commands. An egocentric and vain man, by July Kirby Smith was looking for an opportunity to regain the glory of Manassas.2

Edmund Kirby Smith. Madison County Historic Sites.

Kirby Smith had traveled down from Knoxville to meet his counterpart, a man he later described to his wife as “a grim old fellow, but a true soldier.” General Braxton Bragg was commander of the Army of the Mississippi. Bragg hailed from a North Carolina family of social outcasts; some question exists as to whether he was born while his mother was in jail or shortly after she completed her sentence. Bragg’s father pushed him into a military career, so the future general graduated from West Point in 1837 and spent the next eighteen years in the U.S. Army, seeing action against the Seminoles in Florida and in the Mexican War. His achievements at the Battle of Buena Vista in 1847 made him a national hero despite notable blots on his record that included two court-martials, an attempted assassination attempt by his subordinates and a reputation for extreme contentiousness. Bragg cast his lot with the Confederacy in 1861, and by 1862 was known as a tough drillmaster but a solid subordinate officer. He took command of the Army of Mississippi in mid-June, just six weeks before this meeting with Kirby Smith. Despite his shorter tenure in top command, Bragg was the senior of the two generals.3

Braxton Bragg. Perryville Battlefield State Historic Site.

As the two men pored over their maps, a grim situation presented itself. For the past eight months, Federal armies had won an unbroken string of victories in the West. Now their forces sprawled all over most of Tennessee, northern Mississippi and northern Alabama. Much of this damage had been accomplished by two major Federal armies. Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee was operating between Nashville and Memphis, while Major General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio occupied much of middle Tennessee between Nashville and the Cumberland Plateau outside Chattanooga. At that moment, Buell’s Yankees were slowly advancing toward Chattanooga, gateway to Atlanta and the Southern heartland. The war in the West appeared to be nearing a major turning point.4

Don Carlos Buell. Perryville Battlefield State Historic Site.

The path of war in the Western Theater had been full of dramatic twists and turns up to this point. In many of the shifts, the key had been Kentucky. When North and South divided in the spring of 1861, Kentucky found itself torn between a pro-Union legislature and a pro-secession governor. A compromise declared Kentucky neutral, effectively creating a buffer zone between the Union and the Confederacy stretching from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River. Union armies gathered north of the Ohio River, while in Tennessee Confederate forces coalesced around Nashville and northern border cities. Neither side wanted to provoke Kentucky into joining the other camp. Tension rose during the summer of 1861 as each side waited for the other to tip the balance.

Coincidentally, both U.S. president Abraham Lincoln and Confederate president Jefferson Davis were native Kentuckians. Davis had been born near Hopkinsville in June 1808, while Lincoln followed the next February about one hundred miles east at Hodgenville. Each man knew that his native state would confer great advantages to whichever side controlled it. Kentucky offered a good pool of recruits for an army, while rich farmland could supply plentiful foodstuffs. Armies in the 1860s depended on horses and mules to operate, and the central Bluegrass region was one of the best sources of horseflesh in North America. Geographically, Kentucky touched all of the important rivers for the Union war effort: the Ohio, the Tennessee, the Mississippi and the Cumberland. These watercourses offered good invasion and supply routes for U.S. forces, while the Confederates could use them as effective obstacles to any Union advance. Lincoln summed up the state’s importance when he wrote, “I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game.”5

The delicate balance in the West was upset in early September 1861 when a Confederate force under General Leonidas Polk moved into Kentucky and captured the town of Columbus on the Mississippi River. This act, spurred by erroneous reports of Federal troops in Paducah, set in motion a race for the state as both sides moved to seize territory. The Kentucky General Assembly in Frankfort voted to remain loyal to the United States, while in late October a separate convention in Russellville created a provisional government and passed an ordinance of secession. Kentucky was admitted into the Confederate States of America. The onset of winter found the Confederates in possession of the southern third of the state, while the rest had fallen into Union hands.

Leonidas Polk. Perryville Battlefield State Historic Site.

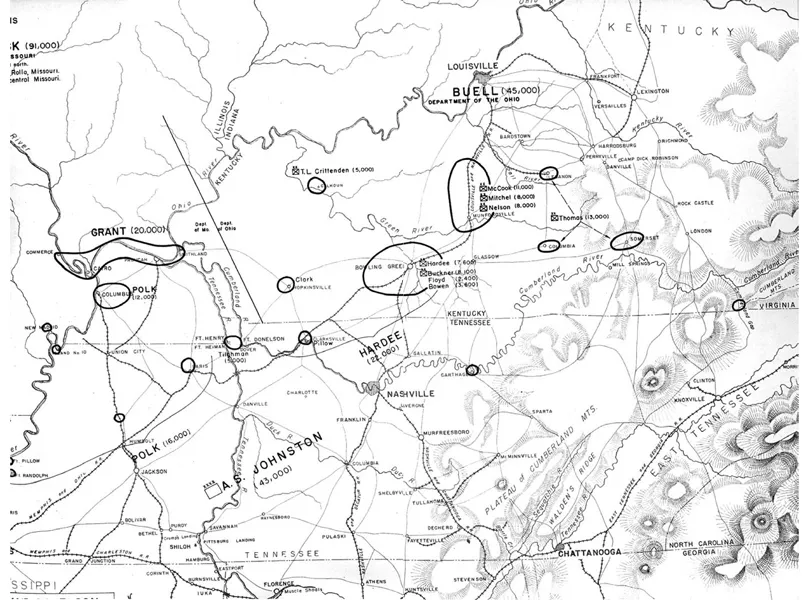

Confederate forces from Tennessee begin their movement into Kentucky. West Point Atlas of American Wars, author’s collection.

Both sides spent the winter consolidating their positions and preparing for a major campaign in 1862. Confederate forces, now commanded by Kentucky-born general Albert Sidney Johnston, set up a thin defensive line across southern Kentucky. One of the major weaknesses of Johnston’s position was that the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers led southward through his defenses; any determined thrust by Federal troops along those waterways could unhinge his whole line.

Buell’s army tested the Confederate line in January, smashing the eastern flank in the Battle of Mill Springs, near Somerset. Grant’s force at Paducah next moved south into Tennessee, and in February captured Forts Henry and Donelson and sixteen thousand men. At a stroke, Johnston’s army in Kentucky was outflanked and its lines of communication to Nashville threatened with rupture. Grant moved up the Tennessee River to Pittsburg Landing near the Mississippi border, while Buell surged toward Nashville.6

Faced with the prospect of a defeat in detail, Johnston was forced to retreat. He abandoned Nashville and decided to concentrate his scattered commands at Corinth, Mississippi, an easy march from Grant’s camp. Polk joined him in Corinth, as did reinforcements under Braxton Bragg from Pensacola. At dawn on April 6, Johnston attacked Grant at Pittsburg Landing. The battle lasted all day and came excruciatingly close to driving Grant’s army into the river, but at the cost of Johnston’s life. Much of Buell’s army arrived that evening and crossed the river, making good Grant’s losses from the day’s fighting. The combined Federal forces counterattacked the next day and drove the Confederates (now under General P.G.T. Beauregard) from the field in disorder. Thus ended the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, or Shiloh, as the Confederates called it—the first truly great battle of the Civil War.7

After Shiloh, both sides reorganized. Beauregard licked his wounds in Corinth, while the Federal armies prepared to follow up their victory. Major General Henry W. Halleck, the Federal supreme commander in the West, came to Pittsburg Landing and assumed command of both Grant’s and Buell’s armies. In late April, Halleck’s force, now numbering 100,000 men, moved south on a methodical advance toward Corinth. The Union troops averaged one mile of progress per day and after a month finally arrived at Corinth to find it deserted. Beauregard had retreated south to Tupelo without a fight.

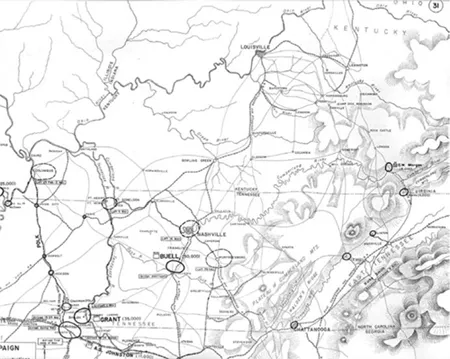

The Western Theater on the eve of the Battle of Shiloh. West Point Atlas of American Wars, author’s collection.

Instead of pursuing his enemy to destruction, Halleck now divided his forces in an effort to capture territory. In June, Grant’s army shifted west and northwest to secure Memphis and West Tennessee, while Buell’s Army of the Ohio was ordered eastward from Corinth toward the critical rail junction of Chattanooga. If Buell captured that city, he would hold the gateway to the Deep South and be just one hundred miles from Atlanta.8

Grant met with swift success in West Tennessee, but Buell’s movement progressed slowly due to supply problems. The Federals had to depend on one railroad that was easily cut by Confederate marauders. The enemy had also destroyed much of its infrastructure and rolling stock, including two large bridges over the Tennessee River. The Army of the Ohio was forced to rebuild as it marched in the heat of a Mississippi and Alabama summer. Although a small detachment of Buell’s army had shelled Chattanooga, his main body was only just approaching the city by late July. It had taken his men six weeks to travel from Corinth to the Cumberland Plateau.9

The Confederates perceived the threat to Chattanooga and had not been idle. Bragg replaced Beauregard after the latter took ill, and one of the first messages he received was a plea for help from Kirby Smith in East Tennessee. In addition to Buell’s advance to the south, Kirby Smith also was eyeing nine thousand Federals under Brigadier General George Morgan, who had occupied Cumberland Gap and appeared poised to strike toward Knoxville. East Tennessee faced threats from both the north and southwest, and a Federal pincer movement faced a high probability of success. Bragg responded to Kirby Smith’s concerns and moved his entire army by rail to Chattanooga in late July. Thus, Bragg and Kirby Smith came face to face on July 31 to plan their next move.10

Several options presented themselves. Both men rejected a defensive strategy and decided to take the initiative. Bragg proposed a campaign to retake Nashville. In addition to being the key to middle Tennessee, Nashville was also the only Confederate capital city in Union hands at that point in the war; a victory th...