eBook - ePub

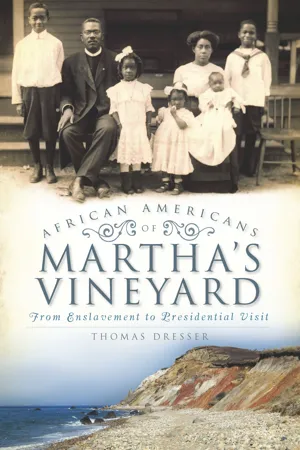

African Americans of Martha's Vineyard

From Enslavement to Presidential Visit

- 195 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

African Americans of Martha's Vineyard have an epic history. From the days when slaves toiled away in the fresh New England air, through abolition and Reconstruction and continuing into recent years, African Americans have fought arduously to preserve a vibrant culture here. Discover how the Vineyard became a sanctuary for slaves during the Civil War and how many blacks first came to the island as indentured servants. Read tales of the Shearer Cottage, a popular vacation destination for prominent blacks from Harry T. Burleigh to Scott Joplin, and how Martin Luther King Jr. vacationed here as well. Venture through the Vineyard with local tour guide Thomas Dresser and learn about people such as Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates and President Barack Obama, who return to the Vineyard for respite from a demanding world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access African Americans of Martha's Vineyard by Thomas Dresser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

CHATTEL

The sound of gunfire echoed off the variegated cliffs of Gay Head, on the southwest corner of the island of Martha’s Vineyard. A young man was drawn to the sound of the shots and hurried from his home on the shores of Squibnocket, a great freshwater lake not far from the clay cliffs. Anxiously, he peered around the bushes that cluttered the tops of the cliffs, curious at the unfamiliar blasts of musket fire below.

He watched as Her Majesty’s Ship Cerberus, a twenty-eight-gun frigate of the Royal Navy, chased an American sailing ship, which was laden with supplies. The English ship fired on the American coaster, and after a small skirmish, the coaster erupted in flames. Or perhaps the Americans set the ship afire to prevent capture. It was difficult to determine what was happening from his secreted vantage point, more than 150 feet above the shore. The young man witnessed the crew from the Cerberus board small barges and paddle after the coaster, intent on extinguishing the fire to seize the supplies, before the ship was fully engulfed in flames.

Given the height of the cliffs, covered with shrubs and small bushes, the young man, whose name was Sharper Michael, observed a neighbor, one Abner Mayhew, dash down the clay escarpment to the beach below and begin to shoot at the redcoats in their barges. Sharper felt a surge of loyalty to join Mayhew and protect their homeland from the invading British. And now the British returned fire at the rebellious colonists. From atop the cliffs, Sharper Michael seized a gun and opened fire on the British barges. His brave efforts, allied with Mayhew’s gunfire, caused the British sailors to turn back and retreat to their mother ship. It was a proud moment for the young Vineyarder.

Sharper Michael stood on the cliffs of Gay Head and fired at the British redcoats. Two hundred years ago, the clay cliffs stood 150 feet above the shore. Photo by Joyce Dresser.

The captain of the Cerberus was outraged at the audacity of the Vineyarders and vowed to seek revenge because they had fired on Her Majesty’s Ship. John Symons recorded in his log on September 1, 1777, that “Our boats went and burnt the vessel,” which, the captain claimed, was loaded with rum, sugar and other war supplies.2

***

Sharper Michael was born a slave in the town of Chilmark on Martha’s Vineyard in 1742, the son of Rosa, an African slave owned by Zacheus Mayhew. Sharper’s father most likely was Caesar Michael, from Guinea (b. 1709), another slave owned by Mayhew. Zacheus Mayhew intended to set Sharper Michael free, and with that understanding, Sharper moved from Chilmark to Gay Head, now Aquinnah, where he was living at the time of the skirmish. The Bristol County Supreme Judicial Court noted, in 1816, “Mayhew agreed to emancipate him, but no Bond was given…as required by the statute regulating the emancipation of slaves.”3 Sharper fathered two children with another slave, Rebecca, owned by Cornelius Bassett of Chilmark. Their children were Nancy and James Michael.

Zacheus Mayhew, Sharper’s master, was only one of many Vineyard slaveholders in the 1700s. He was involved in the town militia and elected captain. Sharper’s father, Caesar, served in the militia in the late 1750s, under Zacheus, who was listed in town records of the 1730s as a licensed innkeeper in Chilmark. Zacheus’s brother, Zachariah, also served as a captain in the militia, but spent his time primarily as a missionary to the local Native American Wampanoags.

Sharper got around. After he moved to Gay Head, he married Lucy Peters, a Native American, in November 1775; they had a daughter, Marcy, born the next year. They may have also had a son, Cesar.

As a freed slave, Sharper Michael was accepted by the community of Gay Head, and his act to repel the invasion by the crew of the Ceberus was certainly a heroic deed, recognized and greatly appreciated by his neighbors. Unfortunately, Sharper never lived to earn credit for his bravery. He died from “a wound which he received in his head by a musketball,” according to a witness of the attack.

Years before, the King of England had commissioned maps to be drawn by captains of British ships patrolling along the coast.4 The accuracy of those early maps was amazing. At the time of the skirmish with the Ceberus, the cliffs rose higher and protruded farther out to sea than they do now. The clay cliffs sag with groundwater but do not erode as quickly as the nearby sandy shores. When Sharper was standing on the cliffs, the ground may have been squishy but still firm to the foot. And because of these early maps, Captain Symons of the Ceberus knew the coastline and was prepared to meet and intercept the American cargo vessel.

Sharper Michael’s efforts went unrecorded at the time. A newspaper story in the Vineyard Gazette reported the attack, decades later: “In the meantime, a negro procured a howitzer with which he began to bombard the invaders from the cliff above and they were finally compelled to draw off without having effected their purpose…with so many wounded that they must tow one of the barges out.” Sharper was credited with repulsing the invading British.

The article continues: “The Englishman [ship] was highly incensed at being thus paid back in his own coin and stood off and on all day, shelling the coast, but the only damage he [the British ship] did was to a negro whose curiosity led him to the cliff to see what might be doing and got in the way of an English ball.”

Sharper Michael proved his heroism, even as he was “cut down in his prime, the first Vineyard casualty in the colony’s struggle for independence.”5 It is of note that this may have been the only casualty of the American Revolution on Vineyard soil, as the other recorded invasion occurred the following year, in the autumn of 1778, when General Grey sailed his armada of British warships into Vineyard Haven harbor and demanded local farmers turn over their sheep and cattle. Some ten thousand sheep were marched down Island to the harbor and led aboard ships, which sailed off to Newport, Rhode Island, where the sheep were killed to feed the British in the winter of 1778. No casualties occurred on the Vineyard in that incident.

Sharper Michael was the first Vineyarder killed in the American Revolution, and, like Crispus Attucks, who was shot and killed by the British in the Boston Massacre of 1770, he was an African American. And, as an African American defending his homeland from attacking forces, Sharper Michael exemplified the conflict of a slave, or former slave, who rose to exhibit brave deeds in a crisis. Yet the story of his bravery bears the underlying tone that Sharper Michael was once a slave, right here on Martha’s Vineyard.

***

The story of Sharper Michael’s progeny is a winding tale with numerous detours and distractions, as it meanders through several generations of African Americans on Martha’s Vineyard. Unfortunately, few records remain of African Americans who were enslaved, and their stories are limited to worn and weathered slips of paper that record a financial transaction between two white people over the ownership of a black person. The best we can do is to acknowledge these faded forms of servitude and wonder whom the people were who lived under the yoke of slavery.

The issue of slavery as an economic force is debated to this day. Economist Paul Krugman recalled a professor who argued there is no point in enslaving people if they have nothing to offer, but if there is cotton to plant, ground to till, labor to be done and a financial gain to be made, it is possible to make a profit off the variance between what the slaves produce and the cost of their upkeep. That is the economic rationale for slavery.

The earliest notice of a slave transaction6 on Martha’s Vineyard occurred on August 24, 1703, when Samuel Sarson, grandson of Massachusetts governor Thomas Mayhew, sold an African American woman, valued at twenty pounds. We have no idea of her name, age or what became of her.

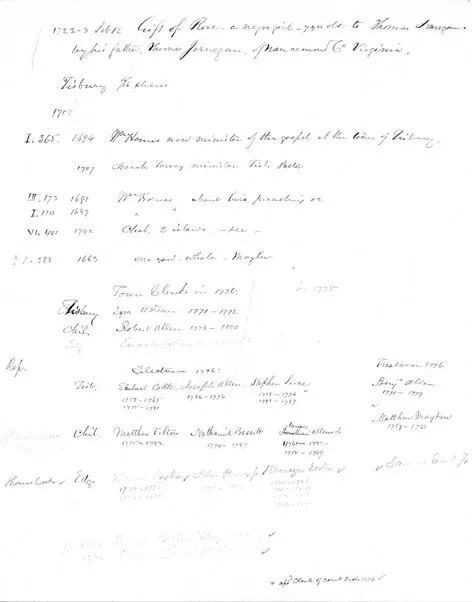

A familial transaction, dated February 12, 1722, reads: “one neager garll a Bout sevauen years old named Rose.” This “gift” was presented to Thomas Jernegan by his father, Thomas Jernegan Sr. of Virginia. Courtesy of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum.

The Martha’s Vineyard Museum has a document that reads, “Know all men by these presents that Zach. Mayhew, Esq. for 150 lb gold paid by Ebenez Hatch of Falmouth, Bargained, Sold and Delivered unto him a negro boy called Peter, the said Negro Boy to have and to hold to the use of the said Eben Hatch’s heirs, executors administrators and assigns for Ever.” It was dated June 19, AD 1727, and signed by Zacheus Mayhew, the slave master of Sharper Michael. At the bottom of the page an addendum reads: “boy will be 11 years November 2, 1727.”

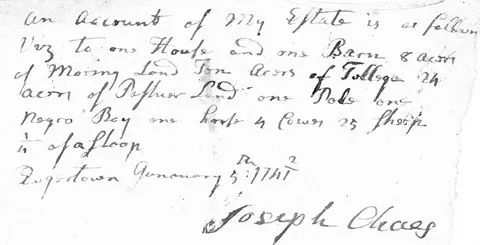

Another listing revealed that Ebenezer Allen of Chilmark, who at one time held an innkeeper’s license, owned negroes valued at £200. This was dated December 4, 1734. A will from Joseph Chase, also housed in the museum, details the specifics of his estate, including “one Negro boy.” It was dated January 5, 1741. That same year, a Jane Cathcart of Chilmark granted freedom to Ishmael Lobb, apparently a slave on her land.

Across Vineyard Sound, a bill of sale in Falmouth, dated December 17, 1745, reads, “Then receivd of benjaman gifford forty shilings in Cash of ye old tener towards freeing my negor boy fortunatious sharper by name, att the age of thirty five years as witness my hand. John Hammond.”7 The archaic spelling does nothing to diminish the horrors of servitude and the sale of human beings as personal property.

“An account of my estate, so follows one House, one Barn and Land of 10 acres and…one Negro Boy.” This was listed in Joseph Chaces’s estate. Courtesy of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum.

Another fragmented document, also from Falmouth, and undated, is a pitiful petition from an African American slave named Cofe the Negro, who pleads that he has “a very great desire to be free from my Bondag which I have lived so long in” and goes on to state that he “should be very thankfull if the people would be of such bountifull hand as to contribute something To me.” More than thirty Falmouth residents donated small sums of money for Cofe’s freedom.

The saga of slavery continued on the Vineyard, with the sale of Black Manoel to a pair of Yankee sea captains in August 1768. The transaction assured the captains that “I bought [Black Manoel] on the Island of St. Michaels without any element of sickness” and that the slave was sold for a quantity of whale oil “to said gentlemen for being fully satisfied of his value.”

Charles Banks, in his mammoth History of Martha’s Vineyard (1911), noted the slaveholder Abraham Chase, ferry operator, owned four negroes valued at ć54. Colonel Cornelius Bassett, who also held an innkeeper’s license, once owned a negro appraised at ć300. He was the slave master who owned Rebecca, the African slave who bore two children with Sharper Michael.

A statement in the Martha’s Vineyard Museum files reveals that on October 10, 1778, one Marshal Jenkins “Rec’d of Beiah Norton 26 lb 11 shilings and 1 peney in full ballance for Zeb Crafman and my Negro Mingdlas.” Even with eighteenth-century spelling and English currency, we understand that Mingdlas was sold as a slave.

Ms. Hammond made a telling observation as she recounted numerous financial transactions in the sale of slaves on the Vineyard. “As property,” she wrote, “it seems, slaves were documented with even less care than most land holdings.”

On occasion, mitigating circumstances acknowledged a hint of humanity in this barbarous system. An article described a house once owned by Isaac Daggett, located in Scrubby Neck, across from the present airport. “He was a slave owner, it is said and had a male slave named Caesar.” Daggett was fearful he would lose his human property, so he “offered to grant Caesar his freedom for $15, which offer was accepted.” Caesar settled nearby, and the area became known as Caesar’s Field.

And then there’s Rebecca, the African woman who bore two children with Sharper Michael. Intermarriage was common between African American slaves and the Native American population who flourished in Gay Head, Christiantown and Chappaquiddick Island. When black men or women intermarried with Native Americans, the African Americans obtained rights to tribal lands. And that is what happened to Rebecca.

Rebecca, or Beck as she was known, was taken from Guinea in West Africa, survived the grueling ordeal of the middle passage to America and became a slave on Martha’s Vineyard. She was owned by Colonel Cornelius Bassett of Chilmark. The timeline of her life is sketchy, but at one time Rebecca was married to Elisha Amos, a Wampanoag also known as Jenoxett. Rebecca and Elisha had no known offspring. Elisha had substantial property holdings, including land around Roaring Brook, a farm in Gay Head and a home in Christiantown. When Elisha died, in 1763, he willed some property, his livestock and home to Rebecca, his “beloved wife,” for the rest of her life. Thus, during her lifetime, she was a landowner and a slave simultaneously. The field nearby was known as Rebecca’s Field. This site is now the Land Bank property of Great Rock Bight Preserve off North Road in Chilmark. A plaque in Rebecca’s honor was placed along the pathway, reading, in part, “Rebecca, woman of Africa, She married Elisha Amos, a Wampanoag…[and] died a free woman in this place in 1801.”

Yet Rebecca Amos was also a slave of Colonel Cornelius Bassett, who lived at what is now Flanders Farm, farther up North Road, also in Chilmark. And it was during the period between Elisha’s death in 1763 and Sharper Michael’s death in 1777 that Rebecca and Sharper spent time together. It is believed that Rebecca was the first person to spot General Grey’s warships as he approached Holmes Hole in the autumn of 1778; she sounded the alarm.

Rebecca inherited property from her husband, Elisha Amos, at what is now known as Great Rock Bight. Yet she was a slave for Colonel Bassett at this farm in Chilmark. Photo by Joyce Dresser.

When Colonel Bassett died, in 1779, Rebecca’s children with Sharper Michael, Nancy, age seven, Pero, age eighteen, and perhaps a third child, Cato, were sold in a slave auction to Joseph Allen of Tisbury. Rebecca died in 1801, a free woman, and apparently owned that property for the duration of her life, living in the house and working the land. And that’s where the Michael family saga pauses, temporarily.

***

At the beginning of the Revolution, about six thousand slaves lived in Massachusetts. Yet the population of African Americans on Martha’s Vineyard was very small. Most of the people who came to the Vineyard of their own volition were drawn by employment as mariners or laborers.

Charles Banks compiled population figures for the latter part of the eighteenth century. Because only three towns were incorporated at the time, the numbers are distorted when compared to current statistics. Edgartown included Oak Bluffs prior to 1880. According t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Prologue

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Chattel

- Chapter 2 Abolition

- Chapter 3 Fugitive

- Chapter 4 Emancipation

- Chapter 5 Pacesetters

- Chapter 6 Promise and Prejudice

- Chapter 7 Civil Rights

- Chapter 8 Social Activists

- Chapter 9 Friends and Family

- Chapter 10 Heritage Trail

- Chapter 11 Mr. President

- Chapter 12 Prominent People

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author