- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

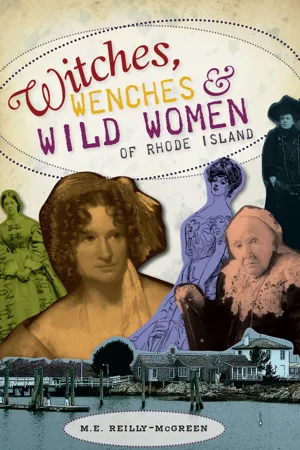

Witches, Wenches & Wild Women of Rhode Island

About this book

Discover the most fearsome and fascinating women to ever live in the Ocean State in this collection of wild historical profiles.

In Witches, Wenches & Wild Women of Rhode Island, local historian M.E. Reilly-McGreen reveals true tales of women who caused scandals in their day. It's a compendium of rebellious deeds, outlandish gossip, and superstition run amok.

Mercy Brown was a nineteen-year-old consumption victim thought to be a vampire. Locals were so afraid of Mercy that her body was exhumed to perform a ritual banishment of the undead. Goody Seager was accused of infesting her neighbor's cheese with maggots by using witchcraft. According to legend, Tall "Dutch" Kattern was an opium-eating fortuneteller whose curse set a ship aflame after its crew cast her ashore.

Along with these tales, you'll read of revolutionaries, like Julia Ward Howe, who invented Mother's Day; and religious reformers like Anne Hutchinson, said to be the inspiration for Hawthorne's heroine in The Scarlet Letter; and many others.

In Witches, Wenches & Wild Women of Rhode Island, local historian M.E. Reilly-McGreen reveals true tales of women who caused scandals in their day. It's a compendium of rebellious deeds, outlandish gossip, and superstition run amok.

Mercy Brown was a nineteen-year-old consumption victim thought to be a vampire. Locals were so afraid of Mercy that her body was exhumed to perform a ritual banishment of the undead. Goody Seager was accused of infesting her neighbor's cheese with maggots by using witchcraft. According to legend, Tall "Dutch" Kattern was an opium-eating fortuneteller whose curse set a ship aflame after its crew cast her ashore.

Along with these tales, you'll read of revolutionaries, like Julia Ward Howe, who invented Mother's Day; and religious reformers like Anne Hutchinson, said to be the inspiration for Hawthorne's heroine in The Scarlet Letter; and many others.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Witches, Wenches & Wild Women of Rhode Island by M. E. Reilly-McGreen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THIRTEEN WITCHES AND A VAMPIRE

TUGGIE BANNOCK: NARRAGANSETT’S WOULD-BE WITCH

Perhaps the most menacing figure in witch folklore is the terrible Baba Yaga of Russia. This ancient crone was mercurial in nature. Sometimes she assisted the intrepid youth or maid who crossed her path. Other times she ate those who crossed her. Baba Yaga’s other mark of distinction was her home. Built atop giant chicken legs, the old hag’s hut was the first mobile home. Don’t be fooled by this seemingly comical mode of travel, though. To be menaced by Baba Yaga and her magical conveyance was to tangle with a fearsome and formidable monster.

Baba Yaga was everything Tuggie Bannock wished to be but wasn’t.

In all likelihood, Narragansett witch Tuggie Bannock is like Baba Yaga in one respect: she is probably fictional. The resemblance ends there, however. Bannock is a comical figure in local folklore. A former slave, Bannock eked out a living by hiring herself out for odd jobs and telling the occasional fortune. Her troubles came as the result of botched spells and ineffective hexes.

One Bannock story has the old witch angry with a local tinker by the name of Bosum Sidet. Poor old Bosum broke her favorite copper teakettle, and Bannock’s wrath was fierce. Alice Morse Earle writes in her book, In Old Narragansett, that Bannock’s “charm was, alas, a malignant one, a ‘conjure’ that she angrily decided to work upon him as a revenge.” Lest there be any confusion about Bannock’s intent, Earle continues, “This charm was not a matter of a moment’s hasty decision and careless action; it required some minute and varied preparation and considerable skill to carry it out successfully, and work due and desired evil.”

Earle writes that Bannock gathered the charm’s necessary ingredients: twigs from a bush by Bosum’s house, hairs clipped from the tail of his cow and

a few rusty nails, the tail of a smoked herring, a scrap of red flannel, a little mass of “grave dirt” that she had taken from one of the many graveyards that are dotted all over Narragansett, and, last of all, that chief ingredient in all charms—a rabbit’s foot…[These] were thrown into a pot of water that was hung upon the crane over a roaring fire.

Bannock’s noxious brew suited her appearance on this occasion. Earle describes her as

tall and gaunt, with long bony arms, and skinny claws of hands, with a wrinkled, malicious, yet half-frightened countenance, surrounded by little pigtails of gray wool that stuck out from under her scarlet turban…she stood like a Voodoo priestess eagerly watching and listening.

Still, Bannock was unprepared when an unseen assailant pushed her from behind. She thought she’d conjured a moonack, an evil creature that, legend holds, would strike Bannock dead if she were to look at it. In her moment of terror, the would-be witch turned to prayer, promising to mend her wicked ways if she were spared.

Bannock never saw the four little boys who snuck into her hovel to retrieve the bobsled that had forced her to the floor. She only heard with relief the retreat of some heavy thing as it dragged itself back out her door. When the old witch was sure she was alone, she “tremblingly arose, closed the door, swung the pot off the fire, seized a horseshoe and prayer-book, and went to bed.”

It was to old Tinker Bosum’s advantage that Tuggie Bannock’s charms had a tendency to backfire. No reports of his having come to any harm exist.

MERCY BROWN: ETERNALLY BEWITCHED AND BEDEVILED

Mercy Lena Brown a witch? At first blush, it may seem erroneous or, at the very least, odd that Rhode Island’s most famous vampire would be called a witch, but folklore doesn’t really differentiate between the two. Many cultures believed that witches fed on human blood. The Greek lamia feasted on children. The Russian Baba Yaga also had a bloodlust for children, though she preferred hers roasted. Egyptians, Celts and Europeans had their hags, who would sit on their sleeping victims, feasting on their blood or breath, depending on their preference, in a process called, alternately, hagging or witch riding.

The headstone of Mercy Brown is often bedecked with trinkets and coins from admirers. Photo by M.E. Reilly-McGreen.

If a witch is defined by her habits, then “witch” is no misnomer when applied to Mercy Brown. She was believed to have fed on her brother, Edwin, who suffered from a wasting illness called consumption. Consumption had claimed the lives of Edwin’s mother, Mary Eliza, his sister, Mary Olive, and, of course, Mercy. The Browns’ second daughter died in January 1892. Many members of the rural community of Exeter subscribed to the folk belief that a demon, a revenant, was responsible for the nighttime assaults on Edwin. Moreover, the folk belief held that the demon would reside in the body of a family member (in this case, Mercy).

And so it was folk beliefs that spurred the disinterment and defilement of Mercy’s remains in March 1892. Among those present were Mercy’s father, George Brown, and the town’s medical examiner, Harold Metcalf. The two men did not believe in the folk remedy themselves, and their involvement was likely motivated by pressure from frightened neighbors. George Brown’s ordeal with consumption was a decade long at the time of the disinterment of the female members of his family.

According to a March 21, 1892 Providence Journal article reprinted in Michael Bell’s seminal work Food for the Dead: On the Trail of New England’s Vampires, Mary Eliza was the first to be disinterred:

On Wednesday morning [March 17], therefore, the doctor went as desired to what is known as Shrub Hill Cemetery, in Exeter, and found four men who had unearthed the remains of Mrs. Brown, who had been interred four years [she had been dead for nine years]. Some of the muscles and flesh still existed in a mummified state, but there were no signs of blood in the heart. The body of the first daughter, [Mary] Olive, was then taken out of the grave, but only a skeleton, with a thick growth of hair, remained.Finally the body of [Mercy] Lena, the second daughter, was removed from the tomb, where it had been placed till spring. The body was in a fairly well preserved state. It had been buried two months. The heart and liver were removed, and in cutting open the heart, clotted and decomposed blood was found, which was what might be expected at that stage of decomposition. The liver showed no blood, though it was in a well-preserved state. These two organs were removed, and a fire being kindled in the cemetery, they were reduced to ashes, and the attendants seemed satisfied.

Those present no doubt felt justified in their unholy task when, upon tearing into the nineteen-year-old’s chest, heart and liver, they found blood. Poor Mercy’s heart was burned on a rock in the Chestnut Hill Cemetery, and, legend says, its ashes were mixed with water and fed to her brother Edwin.

He died anyway. It was Mercy who lived.

A TIMELESS LEGEND

The Providence Journal’s headlines about the Brown family’s tragedy attracted the attention of the world. A sample:

EXHUMED THE BODIES.Testing a Horrible Superstition in the Town of Exeter.BODIES OF DEAD RELATIVES TAKEN FROM THEIR GRAVES.They Had All Died of Consumption, and the Belief Was that Live Flesh and Blood Would Be Found that Fed Upon the Bodies of the Living.

A newspaper clipping about Mercy Lena Brown was found in Dracula author Bram Stoker’s papers. The author, who lived in Europe, published his novel about the iconic vampire in 1897, five years after the Exeter incident. Stoker scholars maintain that the Irish author learned of Mercy’s story after having finished his novel. But that hasn’t stopped Mercy’s fans from speculating how it is, then, that Lucy and Mina, the two female characters in the novel, bear names strikingly similar to Mercy Lena.

Mercy Brown’s story casts a spell whose power endures. In 1979, the Providence Journal chronicled a couple’s efforts to record Mercy Brown’s voice from the grave.

They were unsuccessful. Imagine that.

Their failure doesn’t stop others from trying to have their own experience of Mercy. Police routinely patrol the Chestnut Hill Cemetery on Halloween, when Mercy mania reaches its height. Most people are respectful. Offerings are routinely left on her grave—little things like miniature pumpkins, smooth rocks, flowers, glow sticks and silver coins. Mercy’s headstone has fallen prey to vandals on occasion and even disappeared for a time. It is now tethered to its marble base by an iron collar anchored to a cement cone. The irony here is that iron is a material abhorred by witches and fairies alike. It burns them much in the same way silver does vampires. Witch or vampire, Mercy would no doubt find neither metal to her liking.

Mercy’s influence extends well beyond Exeter even today. In 2008, the History Channel’s Monster Quest series featured Mercy in an episode entitled “Vampires in America.” In 2009, brothers and filmmakers Donald and Paul Mantia of North Providence debuted their forty-minute film The Last American Vampire: Mercy’s Revenge, made with a budget of $1,200. In the movie, Mercy rises from the grave to prey on a group of teenagers stranded in the backwoods of Exeter.

According to folklore, a witch never dies. Neither, it appears, does Mercy Brown.

REBECCA CORNELL: BURN, WITCH, BURN?

Hanged. Drowned. Beheaded. Burned. Such was the fate of many women accused and convicted of witchcraft the world over in the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Some, like Ireland’s Bridget Cleary, met their demise at the hands of their own families. In 1894, Cleary was beaten and burned to death by family and friends, who believed she’d been spirited away by fairy folk and a witch left in her wake.

Lest Cleary’s gruesome death be dismissed as anomaly, consider that it c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I. Thirteen Witches and a Vampire

- Part II. Wenches or Wretches?

- Part III. Wild Women

- Bibliography

- About the Author