eBook - ePub

Norwich in the Gilded Age

The Rose City's Millionaires' Triangle

- 195 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Norwich in the Gilded Age

The Rose City's Millionaires' Triangle

About this book

A photo-filled history of Norwich, Connecticut, and the families, fashions, and fortunes of its elite nineteenth-century residents.

Stroll down Norwich's most fashionable mile of millionaires' mansions and mingle with the extraordinary people who lived and played behind their elegant facades during the glamorous Gilded Age. Wealthy manufacturers and merchants constructed magnificent mansions, many of which survive today, along this trendiest triangle in the glitzy "Rose of New England," conveniently nestled between Boston and New York.

Tricia Staley has uncovered forgotten scandals like the Blackstone baby kidnapping and the bank cashiers who embezzled thousands of dollars from wealthy residents, as well as the drama of fortunes made and lost. Meet Tiffany's founding partner John Young, rubber shoe manufacturing king William A. Buckingham, the Slaters, Greenes, and Hubbards, and more salacious, stylish titans of industry and extravagance.

Stroll down Norwich's most fashionable mile of millionaires' mansions and mingle with the extraordinary people who lived and played behind their elegant facades during the glamorous Gilded Age. Wealthy manufacturers and merchants constructed magnificent mansions, many of which survive today, along this trendiest triangle in the glitzy "Rose of New England," conveniently nestled between Boston and New York.

Tricia Staley has uncovered forgotten scandals like the Blackstone baby kidnapping and the bank cashiers who embezzled thousands of dollars from wealthy residents, as well as the drama of fortunes made and lost. Meet Tiffany's founding partner John Young, rubber shoe manufacturing king William A. Buckingham, the Slaters, Greenes, and Hubbards, and more salacious, stylish titans of industry and extravagance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Norwich in the Gilded Age by Patricia F Staley,Patricia F. Staley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

NORWICH

The Rose of New England

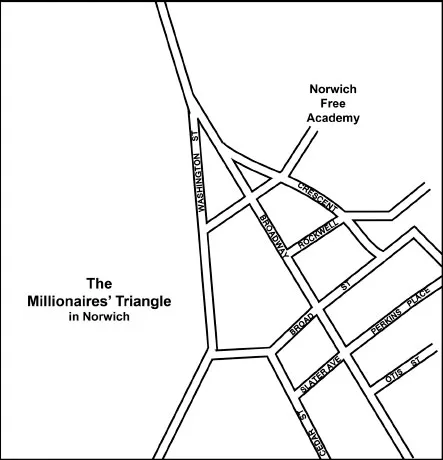

In the center of Norwich, Connecticut, there are two streets lined with large, impressive homes on spacious lots. The streets converge into a single thoroughfare at the apex of a triangle-shaped park. More stately homes line the streets around the park.

It’s almost possible to hear the clip-clop of hooves as a smart pair of high-stepping horses draws a carriage along the street, carrying a well-dressed manufacturer and his companion, a visitor from Boston, to the docks, where they will board the overnight steamboat for New York.

The manufacturer salutes a tall, athletic man dressed in black who is striding up Broadway. “That’s Colonel Perkins,” he remarks to his companion. “He’s eighty-five years old and still goes to the office every day. He’s been treasurer of the railroad almost forty years.”

Later, as they walk toward the docks, the manufacturer stops to shake the hand of another distinguished-looking man. “Senator, good to see you. Are you heading back to Washington?” he asks.

“Yes, but I have business to attend to in New York before I travel south.” The senator smiles, nods and moves off.

The manufacturer remarks, “Senator Buckingham was governor of Connecticut during the war. His family runs the Hayward Rubber Company.”

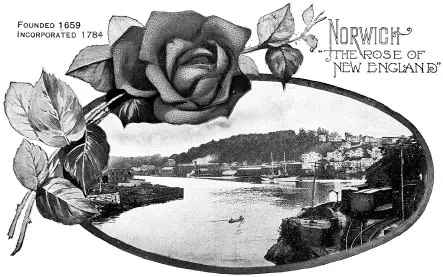

This was Norwich, Connecticut, in the nineteenth century, the home of millionaire manufacturers, businessmen and important political figures. The city was known as “The Rose of New England” for its tree-lined streets and the beauty of its natural surroundings.

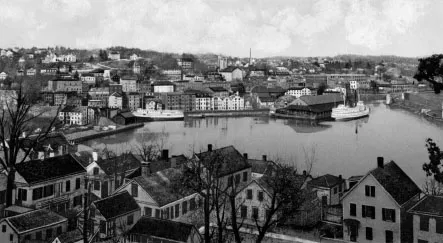

Norwich has been “The Rose of New England” for 150 years. Courtesy of Bill Shannon.

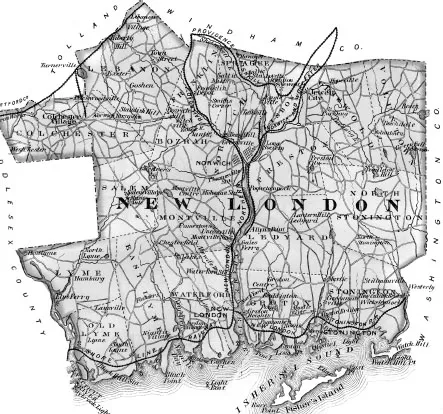

The Norwich story begins in 1659, when a group of settlers left the Saybrook colony at the mouth of the Connecticut River and traveled east on Long Island Sound until reaching the mouth of another river that the group named the Thames (rhymes with James). About twelve miles upriver, the settlers found a natural harbor at the confluence of the Thames and two other rivers and bought a nine-mile-square parcel of land from the Mohegan Indian tribe. If you imagine a letter Y, the Yantic River is the left arm and the Shetucket the right. The base is the Thames, which flows south to Long Island Sound. The town grew up along the riverbanks and on the plain between the arms of the Y.

The first settlement was established about three miles north of the harbor, where the settlers laid out farms surrounding what became the Norwich Town Green.

Throughout the eighteenth century, the importance of shipping increased, and a commercial district grew around the harbor. Maritime trade with England increased, but as Parliament imposed more taxes, Norwich, like towns in the other American colonies, began making its own goods rather than paying the ever-increasing tariffs. Mills and factories were established to provide foodstuffs and textiles.

During the Revolutionary War, its location halfway between New York and Boston put Norwich in the thick of the independence effort. Two key figures of the Revolution lived in the city. One was Samuel Huntington, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and president of the Continental Congress (1779–81) when the Articles of Confederation were adopted. The other was the brilliant general-turned-traitor Benedict Arnold, who spent his boyhood in the city.

This map of New London County shows the Thames River from New London north to Norwich. The Yantic River is the left fork at the top of the map, and the Shetucket to Greeneville is to the right. Courtesy of the author.

With the end of the war, the city grew in both wealth and population. Between 1800 and 1880, Norwich’s population increased sevenfold, growing about 40 percent every ten years between 1820 and 1860 and then dropping to around 20 percent growth in 1870 and 1880. Overall, the city grew from 3,476 in 1800 to 24,637 in 1900.

Early manufacturing enterprises were mainly along the Yantic River at what was called the Falls, for the nearby waterfall, located off Sachem Street just west of the parade grounds (now Chelsea Parade). A ropewalk and maritime-related ventures were established near the harbor.

The international political situation had a significant impact on Norwich development. As the colonies broke away from England, the flow of trade was diverted away from England, and Americans started to think less about importing and more about manufacturing their own goods. Before the Revolution, the town had an ironworks and factories producing linseed oil, iron wire, stockings, chocolate and paper. By 1790, there was a cotton mill, and in the early 1800s, the Goddard & Williams flour mill was also in operation at the Falls.

Domestic manufacturing became more important as the French and British fought for supremacy in Europe, and warships patrolled the West Indies and Caribbean, the destination of many Norwich ships. Shipping was largely stopped around 1807, when the Embargo Act closed ports up and down the Atlantic Coast. Quick ships with clever masters might evade the French and English warships and privateers, but it proved costly to pay the tribute money that the French, the Spanish or the pirates demanded for passage. Added to that was the threat that American seamen would be impressed into the British navy, and it was enough to make merchants and sea captains alike think twice about sea voyages.

The embargo was followed by the War of 1812, which brought more interruption of shipping. The Norwich fleet had been reduced to twenty to thirty brigs, schooners, coasting sloops or packets. Fewer than ten ship arrivals were recorded in 1811, and only three ships docked in the harbor in all of 1812. American manufacturing became even more important.

In 1813, Goddard & Williams turned to manufacturing cloth. Its mill may have been small by later standards, but it served notice on the intent to make a success of domestic textile manufacturing. About the same time, William C. Gilman established a nail-making factory that used a new invention, a machine that cut the nails more quickly and accurately than could be done by hand.

In 1823, Gilman and five investors from Boston incorporated the Thames Manufacturing Company and built a large factory at the Falls to manufacture cotton. The group included William P. Greene, who established the Thames Company in 1829, with a separate group of investors. They bought the Quinebaug Company mill on the banks of the Shetucket River, the Thames Company mill at the Falls and another mill at nearby Bozrahville. Greene bought property on Washington Street and began the Millionaires’ Triangle.

The Millionaires’ Triangle in Norwich. Illustration by Sally Gonthier.

By 1833, factories at the Falls included a large cotton mill, two paper mills, an iron foundry and a rolling mill.

One papermaking mill was run by Amos H. Hubbard, who began his operation at the Falls in 1818. His father, Thomas Hubbard, was publisher of the Norwich Courier. Amos had spent a few years in Java running a newspaper until the British government took over the island. He outfitted a ship with merchandise and came home to Norwich. Paper was originally made by hand, but Hubbard took advantage of the technology of the age and, in 1830, installed one of the earliest Fourdrinier machines, which mechanized the paper manufacturing process. A few years later, he and his brother, Russell, by then the publisher of the Courier, formed a partnership and established a second, modern paper mill in Greeneville. The partnership ended with Russell’s sudden death in 1857, and not long after, Amos Hubbard sold both paper mills to Greene’s Falls Company.

Later, Charles Converse constructed a building at the Falls that housed a gristmill and cork-making factory and eventually several firearms makers. The cork-making factory used a new invention by Norwich’s Crocker brothers that meant hand-carved corks no longer had to be imported from Europe because they could be made more cheaply by machine in the United States.

Regular steamship service between New York and Boston also helped Norwich to prosper as a shipping center. Construction of the Norwich & Worcester Railroad in 1832–37 provided another way to move goods and people in and out of Norwich. The railroad linked with the steamship line, making it possible to travel from Boston to New York in a single day, and the trip was considered much more comfortable than making the entire journey by ship.

During the Civil War, Norwich once again rallied and saw the growth of its textile, armaments and specialty item manufacturing. Norwich gunsmiths turned out thousands of rifles every week during the war, and its textile mills produced thousands of yards of cotton and wool fabric.

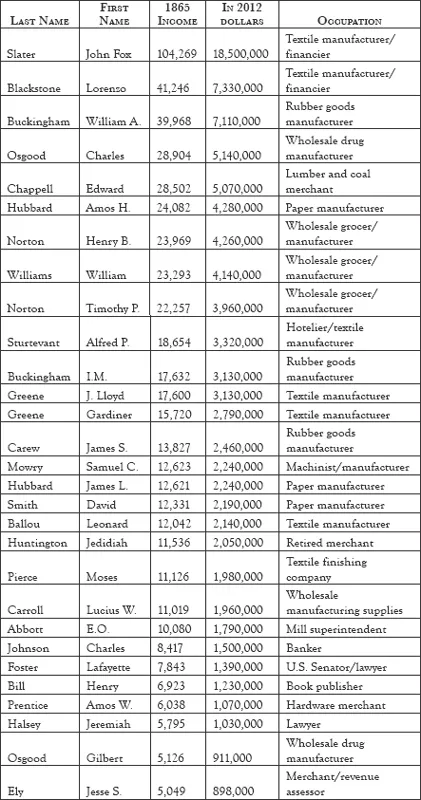

After the Civil War, the federal government began collecting income taxes to retire the massive debt that financed the war. Newspapers published lists of citizens’ incomes, ostensibly to ensure that everyone paid a fair share of the tax burden. The federal census in 1850, ’60 and ’70 included questions about the real and personal estates owned by residents. Together, the census and tax list figures provide some insight into the city’s wealth—and it was impressive. MeasuringWorth.com is a website designed by two University of Illinois–Chicago professors who have developed a way to convert the value of money from one year to another. Their method, used with permission, allowed me to determine the current value of incomes and other measures of wealth ascribed to Norwich’s millionaires.

View overlooking the Norwich Harbor. Courtesy of the author.

In the 1860s, the average annual income was around $200. John F. Slater, by then the city’s wealthiest citizen, had an annual income of $104,000 in 1865, about $18 million© annually in 2012. Just over $5,000 a year would be $1 million today, and Norwich had fifty-four people whose incomes topped that amount, some by a considerable amount. The 1860 census showed a number of people with real estate or personal property holdings in the six-figure range, making them multimillionaires in today’s dollars.

INCOMES OF NORWICH BUSINESSMEN, 1865 AND 2012

These were considered the leading businessmen of Norwich in 1865.

Income does not include dividends from bank, insurance stock or railroad bonds. These are net amounts after taxes and interest paid by the individuals have been deducted.

Incomes from the published 1865 tax list were converted to the equivalent 2012 dollars. Note that the 1865 incomes are minimum amounts because certain dividends were excluded from taxation. Conversions from MeasuringWorth.com.

Norwich’s manufacturing continued to grow after the war, coinciding with the pronounced growth in the national economy. Economists say the 1870s and 1880s were the period of the greatest growth in U.S. history.

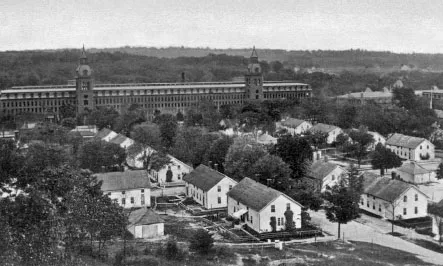

Part of the growth would be attributable to the mammoth Ponemah Mill along the Shetucket River in Taftville, about three miles north of the harbor. The mill was built in 1866–67 by Edward and Cyrus Taft. At 978 feet long and five stories high, with each floor covering an acre and a quarter, it was considered the largest cotton mill under one roof in the world.

Towers of the Ponemah Mill rise over the mill houses of Taftville. Courtesy of Bill Shannon.

The company was organized in 1869 as the Orrey Taft Manufacturing Company with $1.5 million in capital stock. The original shareholders included Norwich residents Lorenzo Blackstone, John F. Slater and Moses Pierce, as well as investors from Massachusetts and Rhode Island. The mill went into operation in November 1871. A second mill was constructed a few years later and a third mill in 1902. When the mill was at full capacity, about 1,500 employees produced several million yards of cotton fabric and cotton yard.

Ponemah was the first mill in the United States to import Egyptian cotton and the first manufacturer of fine cotton fabric. Up to that time, fine fabric was imported from England. One product was soiesette, a silky cotton used in men’s furnishings and pajamas.

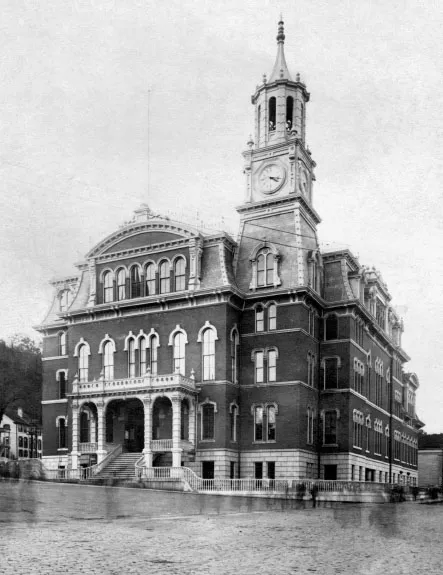

Another building gives strong evidence of the city’s wealth at that time. Norwich City Hall is a large, ornate, imposing building that is a personification of the Gilded Age. Construction of city hall began in 1870 as Norwich’s wealth was skyrocketing. The city had a bona fide millionaire in John F. Slater, with several other residents rapidly approaching millionaire status. Textile factories and firearms makers abounded, and most had done very well indeed during the Civil War.

Norwich City Hall is a fine example of Second Empire style. Courtesy of the author.

The new building combined the functions of a courthouse and a city hall. An act of the legislature designated Norwich the “shire town” or county seat of New London County. An earlier courthouse had been destroyed by fire. At the time, Norwich was divided into the City of Norwich (downtown and the harbor, located largely south of the current Chelsea Parade) and a separate town, called Norwich Town (the earlier settlement, north from Chelsea Parade), as well as several other villages that were eventually incorporated into the city. In 1869, the legislature authorized the city, the town and New London County to jointly construct a new building.

Today, the imposing structure at the intersection of Union Street and Broadway is the Norwich City Hall. It originally housed courts and had a police lockup in the basement, but in the twenty-first century, it holds the offices of the city government and a third-floor meeting room for the Norwich City Council.

The building, considered to be a largely untouched example of Second Empire–style architecture, was designed by Burdick & Arnold, a local architectural firm. The inside, much of which is original, has high metal ceilings, plaster ceiling medallions and original hardware. The interior finish woods are yellow pine, chestnut and black walnut. In the 1870s, the cost of construction was $350,000 (about $43.8 million© in 2012).

The structure is 100 feet long, 108 feet wide and 58 feet high with a French roof. A clo...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Norwich: The Rose of New England

- 2. The Slaters

- 3. The Blackstones

- 4. The Buckinghams, the Aikens and the Carews

- 5. Senator Lafayette S. Foster

- 6. The Greenes and Benjamin W. Tompkins

- 7. The Ballous, the Youngs and the Almys

- 8. General William Williams and Mrs. Harriet Williams

- 9. The Hubbards

- 10. The Elys

- 11. The Lee Family

- 12. Albert P. Sturtevant

- 13. General Daniel P. Tyler

- 14. David A. Wells

- 15. Charles L. Richards

- 16. Edwin C. and Mrs. “Diamond” Johnson

- 17. The Osgoods

- 18. J. Newton Perkins

- 19. The Nortons

- 20. Charles A. Converse

- 21. Colonel George L. Perkins

- 22. Moses Pierce

- 23. Amos W. Prentice

- 24. The Smiths and the Mowrys

- 25. The Charles Johnson Family

- 26. The Erastus Williams Family

- 27. The Carrolls

- 28. Jeremiah Halsey

- 29. Christopher Crandall (C.C.) Brand

- 30. Henry Bill

- 31. Edward Chappell

- 32. Bela Lyon Pratt

- 33. Public Buildings of the Millionaires’ Triangle

- Bibliography

- About the Author